VSI Fortran User Manual

- Software Version:

- VSI Fortran Version 8.3-3 for OpenVMS

- Operating System and Version:

- VSI OpenVMS IA-64 Version 8.4-1H1 or higher

VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 or higher

Preface

Note

In this manual, the term OpenVMS refers to both OpenVMS IA-64 and OpenVMS Alpha systems. If there are differences in the behavior of the VSI Fortran compiler on the two operating systems, those differences are noted in the text.

1. About VSI

VMS Software, Inc. (VSI) is an independent software company licensed by Hewlett Packard Enterprise to develop and support the OpenVMS operating system.

2. Intended Audience

You already have a basic understanding of the Fortran 90/95 language. Tutorial Fortran 90/95 language information is widely available in commercially published books (see the online release notes or the Preface of the VSI Fortran Reference Manual).

You are familiar with the operating system commands used during program development and a text editor. Such information is available in the OpenVMS documentation set.

You have access to the VSI Fortran Reference Manual, which describes the VSI Fortran 90/95 language.

3. Document Structure

Chapter 1, "Getting Started" introduces the programmer to the VSI Fortran compiler, its components, and related commands.

Chapter 2, "Compiling VSI Fortran Programs" describes the FORTRAN command qualifiers in detail.

Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs" describes how to link and run a VSI Fortran program.

Chapter 4, "Using the OpenVMS Debugger" describes the OpenVMS Debugger and some special considerations involved in debugging Fortran programs. It also lists some relevant programming tools and commands.

Chapter 5, "Performance: Making Programs Run Faster" describes ways to improve run-time performance, including general software environment recommendations, appropriate FORTRAN command qualifiers, data alignment, efficiently performing I/O and array operations, other efficient coding techniques, profiling, and optimization.

Chapter 6, "VSI Fortran Input/Output" provides information on VSI Fortran I/O, including statement forms, file organizations, I/O record formats, file specifications, logical names, access modes, logical unit numbers, and efficient use of I/O.

Chapter 7, "Run-Time Errors" lists run-time messages and describes how to control certain types of I/O errors in your I/O statements.

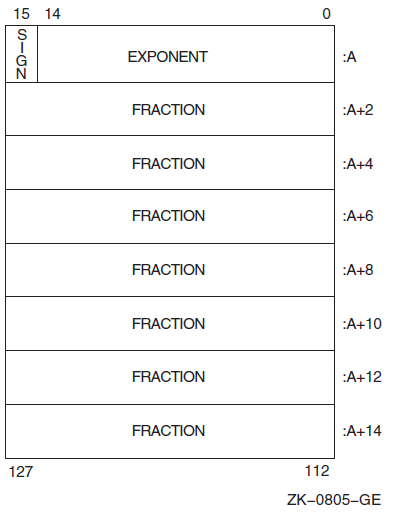

Chapter 8, "Data Types and Representation" describes the native Fortran OpenVMS data types, including their numeric ranges, representation, and floating-point exceptional values. It also discusses the intrinsic data types used with numeric data.

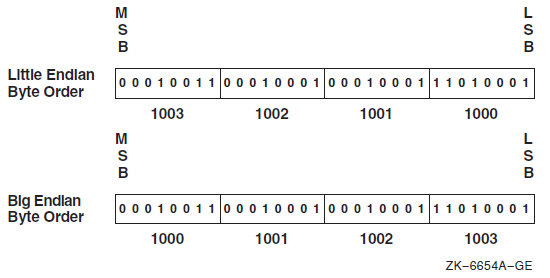

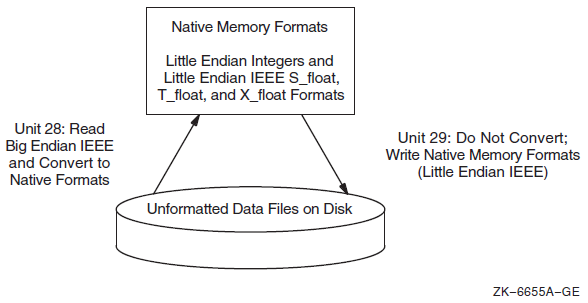

Chapter 9, "Converting Unformatted Numeric Data" describes how to access unformatted files containing numeric little endian and big endian data different than the format used in memory.

Chapter 10, "Using VSI Fortran in the Common Language Environment" describes how to call routines and pass arguments to them.

Chapter 11, "Using OpenVMS Record Management Services" describes how to utilize OpenVMS Record Management Services (RMS) from a VSI Fortran program.

Chapter 12, "Using Indexed Files" describes how to access records using indexed sequential access.

Chapter 13, "Interprocess Communication" gives an introduction on how to exchange and share data among both local and remote processes.

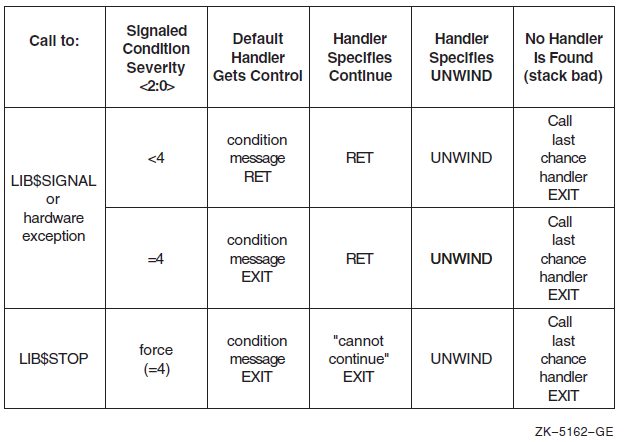

Chapter 14, "Condition-Handling Facilities" describes facilities that can be used to handle—in a structured and consistent fashion—special conditions (errors or program-generated status conditions) that occur in large programs with many program units.

Chapter 15, "Using the VSI Extended Math Library (VXML) (Alpha Only)" provides information on the VSI Extended Math Library (VXML) (Alpha only), a comprehensive set of mathematical library routines callable from Fortran and other languages.

Appendix A, "Differences Between VSI Fortran on OpenVMS IA-64 and OpenVMS Alpha Systems" describes the differences between VSI Fortran on IA-64 systems and on Alpha systems.

Appendix B, "Compatibility: Compaq Fortran 77 and VSI Fortran" describes the compatibility between VSI Fortran for OpenVMS systems and VSI Fortran on other platforms, especially Compaq Fortran 77 for OpenVMS systems.

Appendix C, "Diagnostic Messages" describes diagnostic messages issued by the VSI Fortran compiler and lists and describes messages from the VSI Fortran Run-Time Library (RTL) system.

Appendix D, "VSI Fortran Logical Names" lists the VSI Fortran logical names recognized at compile-time and run-time.

Appendix E, "Contents of the VSI Fortran System Library FORSYSDEF" identifies the VSI Fortran include files that define symbols for use in VSI Fortran programs.

Appendix F, "Using System Services: Examples" contains examples of the use of a variety of system services.

Note

If you are reading the printed version of this manual, be aware that the version at the VSI Fortran Web site and the version on the Documentation CD-ROM from VSI may contain updated and/or corrected information.

4. Related Documents

Describes the VSI Fortran 90/95 source language for reference purposes, including the format and use of statements, intrinsic procedures, and other language elements.

VSI Fortran Installation Guide for OpenVMS I64 Systems or VSI Fortran Installation Guide for OpenVMS Alpha Systems

Explain how to install VSI Fortran.

VSI Fortran online release notes

Provide the most recent information on this version of VSI Fortran. You can view or print the online release notes from:SYS$HELP:FORTRAN.RELEASE_NOTES (text version) SYS$HELP:FORTRAN_RELEASE_NOTES.PS (PostScript version)

- Summarizes the VSI Fortran command-line qualifiers, explains run-time messages, and provides a quick-reference summary of language topics. To use online HELP, use this command:

$HELP FORTRAN Intel Itanium Architecture Software Developer’s Manual

Operating system documentation

The operating system documentation set describes the DCL commands (such as LINK), OpenVMS routines (such as system services and run-time library routines), OpenVMS concepts, and other aspects of the programming environment.

For OpenVMS systems, sources of programming information include the following:OpenVMS Programming Environment Manual

VSI OpenVMS Programming Concepts Manual

OpenVMS Programming Interfaces: Calling a System Routine

VSI OpenVMS Debugger Manual

Alpha Architecture Reference Manual

Alpha Architecture Handbook

For information on the documentation for the OpenVMS operating system, including a list of books in the programmer's kit, see the Overview of OpenVMS Documentation.

OpenVMS VAX to OpenVMS Alpha porting information can be found in Migrating an Application from OpenVMS VAX to OpenVMS Alpha. (For Fortran-specific porting information, see Appendix B, "Compatibility: Compaq Fortran 77 and VSI Fortran").

OpenVMS Alpha to OpenVMS IA-64 porting information can be found in Porting Applications from VSI OpenVMS Alpha to VSI OpenVMS Industry Standard 64 for Integrity Servers.

You can also use online DCL HELP for various OpenVMS commands and most routines by typing HELP. For the Debugger (and other tools), type HELP after you invoke the Debugger. For information on operating system messages, use the HELP/MESSAGE command.

5. OpenVMS Documentation

The full VSI OpenVMS documentation set can be found on the VMS Software Documentation webpage at https://docs.vmssoftware.com.

6. VSI Encourages Your Comments

You may send comments or suggestions regarding this manual or any VSI document by sending electronic mail to the following Internet address: <docinfo@vmssoftware.com>. Users who have VSI OpenVMS support contracts through VSI can contact <support@vmssoftware.com> for help with this product.

7. Conventions

OpenVMS Industry Standard 64 for Integrity Servers

OpenVMS IA-64

I64

All three names — the longer form and the two abbreviated forms — refer to the version of the OpenVMS operating system that runs on the Intel ® Itanium ® architecture.

|

Ctrl/x |

A sequence such as Ctrl/x indicates that you must hold down the key labeled Ctrl while you press another key or a pointing device button. |

|

PF1 x |

A sequence such as PF1 x indicates that you must first press and release the key labeled PF1 and then press and release another key or a pointing device button. |

... |

A horizontal ellipsis in examples indicates one of the

following possibilities:

|

. . . |

A vertical ellipsis indicates the omission of items from a code example or command format; the items are omitted because they are not important to the topic being discussed. |

|

( ) |

In command format descriptions, parentheses indicate that you must enclose choices in parentheses if you specify more than one. |

|

[ ] |

In command format descriptions, brackets indicate optional choices. You can choose one or more items or no items. Do not type the brackets on the command line. However, you must include the brackets in the syntax for OpenVMS directory specifications and for a substring specification in an assignment statement. |

|

| |

In command format descriptions, vertical bars separate choices within brackets or braces. Within brackets, the choices are optional; within braces, at least one choice is required. Do not type the vertical bars on the command line. |

|

{ } |

In command format descriptions, braces indicate required choices; you must choose at least one of the items listed. Do not type the braces on the command line. |

|

bold type |

Bold type represents the name of an argument, an attribute, or a reason. |

|

italic type |

Italic type indicates important information, complete titles of manuals, or variables. Variables include information that varies in system output (Internal error number), in command lines (/PRODUCER= name), and in command parameters in text (where dd represents the predefined code for the device type). |

|

UPPERCASE TYPE |

Uppercase type indicates a command, the name of a routine, the name of a file, or the abbreviation for a system privilege. |

|

- |

A hyphen at the end of a command format description, command line, or code line indicates that the command or statement continues on the following line. |

|

numbers |

All numbers in text are assumed to be decimal unless otherwise noted. Nondecimal radixes — binary, octal, or hexadecimal — are explicitly indicated. |

|

real |

This term refers to all floating-point intrinsic data types as a group. |

|

complex |

This term refers to all complex floating-point intrinsic data types as a group. |

|

logical |

This term refers to logical intrinsic data types as a group. |

|

integer |

This term refers to integer intrinsic data types as a group. |

|

Fortran |

This term refers to language information that is common to ANSI FORTRAN-77, ANSI/ISO Fortran 90, ANSI/ISO Fortran 95, and VSI Fortran 90. |

|

Fortran 90 |

This term refers to language information that is common to ANSI/ISO Fortran 90 and VSI Fortran. For example, a new language feature introduced in the Fortran 90 standard. |

|

Fortran 95 |

This term refers to language information that is common to ISO Fortran 95 and VSI Fortran. For example, a new language feature introduced in the Fortran 95 standard. |

|

VSI Fortran |

Unless otherwise specified, this term (formerly Compaq Fortran) refers to language information that is common to the Fortran 90 and 95 standards, and any VSI Fortran extensions, running on the OpenVMS operating system. Since the Fortran 90 standard is a superset of the FORTRAN-77 standard, VSI Fortran also supports the FORTRAN-77 standard. VSI Fortran supports all of the deleted features of the Fortran 95 standard. |

Chapter 1. Getting Started

1.1. Fortran Standards Overview

American National Standard Fortran 90 (ANSI X3.198-1992), which is the same as the International Standards Organization standard (ISO/IEC 1539:1991 (E))

Fortran 95 standard (ISO/IEC 1539:1998 (E))

VSI Fortran supports all of the deleted features of the Fortran 95 standard.

VSI Fortran also includes support for programs that conform to the previous Fortran standards (ANSI X3.9-1978 and ANSI X3.0-1966), the International Standards Organization standard ISO 1539-1980 (E), the Federal Information Processing Institute standard FIPS 69-1, and the Military Standard 1753 Language Specification.

The ANSI committee X3J3 is currently answering questions of interpretation of Fortran 90 and 95 language features. Any answers given by the ANSI committee that are related to features implemented in VSI Fortran may result in changes in future releases of the VSI Fortran compiler, even if the changes produce incompatibilities with earlier releases of VSI Fortran.

VSI Fortran provides a number of extensions to the Fortran 90 and 95 standards. VSI Fortran extensions to the latest Fortran standard are generally provided for compatibility with Compaq Fortran 77 extensions to the ANSI FORTRAN-77 standard.

When creating new programs that need to be standards-conforming for portability reasons, you should avoid or minimize the use of extensions to the latest Fortran standard. Extensions to the appropriate Fortran standard are identified visually in the VSI Fortran Reference Manual, which defines the VSI Fortran language.

1.2. VSI Fortran Programming Environment

To install VSI Fortran on your system, see the VSI Fortran Installation Guide for OpenVMS I64 Systems or the VSI Fortran Installation Guide for OpenVMS Alpha Systems.

- Make sure you have adequate process memory space, especially if your programs use large arrays as data. Your system manager (or designated privileged user) may be able to overcome this problem by checking and possibly increasing the following:

Your process memory (working set)

Your system manager can use the Authorize Utility to adjust your process working set quotas, page file quota, and limits.

System-wide virtual memory limits

Your system manager can use SYSGEN to change parameters (such as WSMAX and VIRTUALPAGECNT), which take effect after the system is rebooted.

Page file space on your system

Your system manager can use SYSGEN or AUTOGEN to increase page file sizes or create new page files. Your system manager needs to INSTALL any new page files available to the system by modifying system startup command procedures and rebooting the system.

System hardware resources, such as physical memory and disk space

You can check the current memory limits using the SHOW WORKING_SET command. To view peak memory use after compiling or running a program, use the SHOW PROCESS/ACCOUNTING command. Your system manager can use these commands (or SHOW PROCESS/CONTINUOUS) for a currently running process and the system-side MONITOR command.

For example, the following DCL (shell) commands check the current limits and show the current use of some of these limits:$SHOW WORKING_SET...$SHOW PROCESS/ACCOUNTING... Make sure you have an adequate process open file limit, especially if your programs use a large number of module files.

During compilation, your application may attempt to use more module files than your open file limit allows. In this case, the VSI Fortran compiler will close a previously opened module file before it opens another to stay within your open file limit. This results in slower compilation time. Increasing the open file limit may improve compilation time in such cases.

You can view the per-process limit on the number of open files (Open file quota or FILLM) by using the SHOW PROCESS/QUOTA command:$SHOW PROCESS/QUOTA...Your system manager needs to determine the maximum per-process limit for your system by checking the value of the CHANNELCNT SYSGEN parameter and (if necessary) increasing its value.

You can define logical names to specify libraries and directories.

You can define the FORT$LIBRARY logical name to specify a user-defined text library that contains source text library modules referenced by INCLUDE statements. The compiler searches first for libraries specified on the command line and also in the system-supplied default library (see Section 2.4, ''Creating and Maintaining Text Libraries'').

For more information on using FORT$LIBRARY, see Section 2.2.4, ''Using Include Files and Include Text Library Modules''.

You can define the FORT$INCLUDE logical name to specify a directory to be searched for the following files:Module files specified by a USE statement (module name is used as a file name)

Source files specified by an INCLUDE statement, where a file name is specified without a directory name

Text library files specified by an INCLUDE statement, where a file name is specified without a library name

For more information on the FORT$INCLUDE logical name, see Section 2.2.3, ''Creating and Using Module Files'' and Section 2.2.4, ''Using Include Files and Include Text Library Modules''.

If you need to set logical names frequently, consider setting them in your LOGIN.COM file, or ask your system manager to set them as system-wide logical names in a system startup command procedure.

Several other logical names can similarly be used during program execution (see Appendix D, "VSI Fortran Logical Names").

- Your VSI Fortran source files can be in free or fixed form. You can indicate the source form used in your source files by using certain file types or a command-line qualifier:

For files using fixed form, specify a file type of FOR or F.

For files using free form, specify a file type of F90.

You can also specify the /SOURCE_FORM qualifier on the FORTRAN command line to specify the source form for all files on that command line.

For example, if you specify a file as PROJ_BL1.F90 on a FORTRAN command line (and omit the /SOURCE_FORM=FIXED qualifier), the FORTRAN command assumes the file PROJ_BL1.F90 contains free-form source code.

A special type of fixed source form is tab form (a VSI extension described in the VSI Fortran Reference Manual).

- Each source file to be compiled must contain at least one program unit (main program, subroutine, function, module, block data). Consider the following aspects of program development:

Modularity and efficiency

For a large application, using a set of relatively small source files promotes incremental application development.

When application run-time performance is important, compile related source files together (or the entire application). When compiling multiple source files, separate file names with plus signs (+) to concatenate source files and create a single object file. This allows certain interprocedure optimizations to minimize run-time execution time (unless you specify certain qualifiers).

Code reuse

Modules, external subprograms, and included files allow reuse of common code. Code used in multiple places in a program should be placed in a module, external subprogram (function or subroutine), or included file.

When using modules and external subprograms, there is one copy of the code for a program. When using INCLUDE statements, the code in the specified source file is repeated once for each INCLUDE statement.

In most cases, using modules or external subprograms makes programs easier to maintain and minimizes program size.

For More Information:

On modules, see Section 2.2.3, ''Creating and Using Module Files''.

On include files, see Section 2.2.4, ''Using Include Files and Include Text Library Modules''.

On VSI Fortran source forms, see the VSI Fortran Reference Manual.

On recognized file types, see Section 2.2.1, ''Specifying Input Files and Source Form''.

On the types of subprograms and using an explicit interface to a subprogram, see Chapter 10, "Using VSI Fortran in the Common Language Environment".

On performance considerations, including compiling source programs for optimal run-time performance, see Chapter 5, "Performance: Making Programs Run Faster".

On logical names, see the VSI OpenVMS User’s Manual.

1.3. Commands to Create and Run an Executable Program

! File hello.f90

PROGRAM HELLO_TEST

PRINT *, 'hello world'

PRINT *, ' '

END PROGRAM HELLO_TEST

$EDIT HELLO.F90

$FORTRAN HELLO.F90$LINK HELLO

In this example, because all external routines used by this program reside in standard OpenVMS libraries searched by the LINK command, additional libraries or object files are not specified on the LINK command line.

$RUN HELLO

If the executable program is not in your current default directory, specify the directory before the file name. Similarly, if the executable program resides on a different device than your current default device, specify the device name and directory name before the file name.

For More Information:

On the OpenVMS programming environment, see the operating system documents listed in the Preface of this manual.

On specifying files on an OpenVMS system, see the VSI OpenVMS User’s Manual.

1.4. Creating and Running a Program Using a Module and Separate Function

Example 1.2, ''Sample Main Program That Uses a Module and Separate Function'' shows a sample VSI Fortran main program using free-form source that uses a module and an external subprogram.

! File: main.f90

! This program calculates the average of five numbers

PROGRAM MAIN

USE ARRAY_CALCULATOR  REAL, DIMENSION(5) :: A = 0

REAL :: AVERAGE

PRINT *, 'Type five numbers: '

READ (*,'(BN,F10.3)') A

AVERAGE = CALC_AVERAGE(A)

REAL, DIMENSION(5) :: A = 0

REAL :: AVERAGE

PRINT *, 'Type five numbers: '

READ (*,'(BN,F10.3)') A

AVERAGE = CALC_AVERAGE(A)  PRINT *, 'Average of the five numbers is: ', AVERAGE

END PROGRAM MAIN

PRINT *, 'Average of the five numbers is: ', AVERAGE

END PROGRAM MAIN ! File: array_calc.f90.

! Module containing various calculations on arrays.

MODULE ARRAY_CALCULATOR

INTERFACE

FUNCTION CALC_AVERAGE(D)

REAL :: CALC_AVERAGE

REAL, INTENT(IN) :: D(:)

END FUNCTION CALC_AVERAGE

END INTERFACE

! Other subprogram interfaces...

END MODULE ARRAY_CALCULATOR

! File: calc_aver.f90.

! External function returning average of array.

FUNCTION CALC_AVERAGE(D)

REAL :: CALC_AVERAGE

REAL, INTENT(IN) :: D(:)

CALC_AVERAGE = SUM(D) / UBOUND(D, DIM = 1)

END FUNCTION CALC_AVERAGE1.4.1. Commands to Create the Executable Program

$FORTRAN ARRAY_CALC.F90$FORTRAN CALC_AVER.F90$FORTRAN MAIN.F90$LINK/EXECUTABLE=CALC.EXE MAIN, ARRAY_CALC, CALC_AVER

Each of the FORTRAN commands creates one object file (OBJ file type).

The first FORTRAN command creates the object file ARRAY_CALC.OBJ and the module file ARRAY_CALCULATOR.F90$MOD. The name in the MODULE statement (ARRAY_CALCULATOR) in Example 1.3, ''Sample Module'' determines the file name of the module file. The FORTRAN command creates module files in the process default device and directory with a F90$MOD file type.

The second FORTRAN command creates the file CALC_AVER.OBJ ( Example 1.4, ''Sample Separate Function Declaration'').

The third FORTRAN command creates the file MAIN.OBJ ( Example 1.2, ''Sample Main Program That Uses a Module and Separate Function'') and uses the module file ARRAY_CALCULATOR.F90$MOD.

The LINK command links all object files (OBJ file type) into the executable program named CALC.EXE.

$FORTRAN/OBJECT=CALC.OBJ ARRAY_CALC.F90 + CALC_AVER.F90 + MAIN.F90

Compiles the file ARRAY_CALC.F90, which contains the module definition (shown in Example 1.3, ''Sample Module''), and creates its object file and the file ARRAY_CALCULATOR.F90$MOD in the process default device and directory.

Compiles the file CALC_AVER.F90, which contains the external function CALC_AVERAGE (shown in Example 1.4, ''Sample Separate Function Declaration'').

Compiles the file MAIN.F90 (shown in Example 1.2, ''Sample Main Program That Uses a Module and Separate Function''). The USE statement references the module file ARRAY_CALCULATOR.F90$MOD.

Creates a single object file named CALC.OBJ.

$FORTRAN/OBJECT=CALC.OBJ ARRAY_CALC + CALC_AVER + MAIN

$LINK CALC

When you omit the file type on the LINK command line, the Linker searches for a file with a file type of OBJ. Unless you will specify a library on the LINK command line, you can omit the OBJ file type.

1.4.2. Running the Sample Program

$RUN CALC

When you omit the file type on the RUN command line, the image activator searches for a file with a file type of EXE (you can omit the EXE file type).

Type five numbers:55.54.53.99.05.6Average of the five numbers is: 15.70000

1.4.3. Debugging the Sample Program

$FORTRAN/DEBUG/OBJECT=CALC_DEBUG.OBJ/NOOPTIMIZE ARRAY_CALC + CALC_AVER + MAIN$LINK/DEBUG CALC_DEBUG

$RUN CALC_DEBUG

For more information on running the program within the debugger and the windowing interface, see Chapter 4, "Using the OpenVMS Debugger".

1.5. Program Development Stages and Tools

This manual primarily addresses the program development activities associated with implementation and testing phases. For information about topics usually considered during application design, specification, and maintenance, see your operating system documentation or appropriate commercially published documentation.

VSI Fortran provides the standard features of a compiler and the OpenVMS operating system provides a linker.

Use a LINK command to link the object file into an executable program.

|

Task or Activity |

Tool and Description |

|---|---|

|

Manage source files | |

|

Create and modify source files |

Use a text editor, such as the EDIT command to use the EVE editor. You can also use the optional Language-Sensitive Editor (LSE). For more information using OpenVMS text editors, see the VSI OpenVMS User’s Manual. |

|

Analyze source code |

Use DCL commands such as SEARCH and DIFFERENCES. |

|

Build program (compile and link) |

You can use the FORTRAN and LINK commands to create small programs, perhaps using command procedures, or use the Module Management System (MMS) to build your application in an automated fashion. For more information on the FORTRAN and LINK commands, see Chapter 2, "Compiling VSI Fortran Programs" and Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs" respectively. |

|

Debug and Test program |

Use the OpenVMS Debugger to debug your program or run it for general testing. For more information on the OpenVMS Debugger, see Chapter 4, "Using the OpenVMS Debugger" in this manual. |

|

Analyze performance |

To perform program timings and profiling of code, use the LIB$

For more information on timing and profiling VSI Fortran code, see Chapter 5, "Performance: Making Programs Run Faster". |

Use the LIBRARIAN command to create an object or text library, add or delete library modules in a library, list the library modules in a library, and perform other functions. For more information, enter HELP LIBRARIAN or see the VMS Librarian Utility Manual.

Use the LINK/NODEBUG command to remove symbolic and other debugging information to minimize image size. For more information, see Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs".

The LINK/MAP command creates a link map, which shows information about the program sections, symbols, image section, and other information.

The ANALYZE/OBJECT command shows which compiler compiled the object file and the version number used. It also does a partial error analysis and shows other information.

The ANALYZE/IMAGE command checks information about an executable program file. It also shows the date it was linked and the version of the operating system used to link it.

For More Information:

On the OpenVMS programming environment, see the Preface of this manual.

On DCL commands, use DCL HELP or see the VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary.

Chapter 2. Compiling VSI Fortran Programs

2.1. Functions of the Compiler

Verify the VSI Fortran source statements and to issue messages if the source statements contain any errors

Venerate machine language instructions from the source statements of the VSI Fortran program

Group these instructions into an object module for the OpenVMS Linker

The program unit name. The program unit name is the name specified in the PROGRAM, MODULE, SUBROUTINE, FUNCTION, or BLOCK DATA statement in the source program. If a program unit does not contain any of these statements, the source file name is used with $MAIN (or $DATA, for block data subprograms) appended.

A list of all entry points and common block names that are declared in the program unit. The linker uses this information when it binds two or more program units together and must resolve references to the same names in the program units.

Traceback information, used by the system default condition handler when an error occurs that is not handled by the program itself. The traceback information permits the default handler to display a list of the active program units in the order of activation, which aids program debugging.

A symbol table, if specifically requested (/DEBUG qualifier). A symbol table lists the names of all external and internal variables within a object module, with definitions of their locations. The table is of primary use in program debugging.

For More Information:

On the OpenVMS Linker, see Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs".

2.2. FORTRAN Command Syntax, Use, and Examples

The FORTRAN command initiates compilation of a source program.

FORTRAN [/qualifiers] file-spec-list[/qualifiers]

/qualifiers Indicates either special actions to be performed by the compiler or special properties of input or output files.

file-spec-list If source file specifications are separated by commas (,), the programs are compiled separately.

If source file specifications are separated by plus signs (+), the files are concatenated and compiled as one program.

When compiling source files with the default optimization (or additional optimizations), concatenating source files allows full interprocedure optimizations to occur.

_File:Enter the file specification immediately after the prompt and then press Return.

2.2.1. Specifying Input Files and Source Form

If you omit the file type on the FORTRAN command line, the compiler searches first for a file with a file type of F90. If a file with a file type of F90 is not found, it then searches for file with a file type of FOR and then F.

$FORTRAN PROJ_ABC

It searches first for PROJ_ABC.F90.

If PROJ_ABC.F90 does not exist, it then searches for PROJ_ABC.FOR.

If PROJ_ABC.F90 and PROJ_ABC.FOR do not exist, it then searches for PROJ_ABC.F.

For files using fixed form, use a file type of FOR or F.

For files using free form, use a file type of F90.

- You can also specify the /SOURCE_FORM qualifier on the FORTRAN command line to specify the source form (FIXED or FREE) for:

All files on that command line (when used as a command qualifier)

Individual source files in a comma-separated list of files (when used as a positional qualifier)

For example, if you specify a file as PROJ_BL1.F90 on an FORTRAN command line (and omit the /SOURCE_FORM=FIXED qualifier), the FORTRAN command assumes the file PROJ_BL1.F90 contains free-form source code.

2.2.2. Specifying Multiple Input Files

When you specify a list of input files on the FORTRAN command line, you can use abbreviated file specifications for those files that share common device names, directory names, or file names.

The system applies temporary file specification defaults to those files with incomplete specifications. The defaults applied to an incomplete file specification are based on the previous device name, directory name, or file name encountered in the list.

$FORTRAN USR1:[ADAMS]T1,T2,[JACKSON]SUMMARY,USR3:[FINAL]

USR1:[ADAMS]T1.F90 (or .FOR or .F) USR1:[ADAMS]T2.F90 (or .FOR or .F) USR1:[JACKSON]SUMMARY.F90 (or .FOR or .F) USR3:[FINAL]SUMMARY.F90 (or .FOR or .F)

$FORTRAN [OMEGA]T1, []T2

The empty brackets indicate that the compiler is to use your current default directory to locate T2.

FORTRAN qualifiers typically apply to the entire FORTRAN command line. One exception is the /LIBRARY qualifier, which specifies that the file specification it follows is a text library (positional qualifier). The /LIBRARY qualifier is discussed in Section 2.3.27, ''/LIBRARY — Specify File as Text Library''.

Plus signs (+)

All files separated by plus signs are concatenated and compiled as one program into a single object file.

A positional qualifier after one of the file specifications applies to all files concatenated by plus signs (+). One exception is the /LIBRARY qualifier (used only as a positional qualifier).

Concatenating source files allows full interprocedure optimizations to occur across the multiple source files (unless you specify certain command qualifiers, such as /NOOPTIMIZE and /SEPARATE_COMPILATION).

Commas (,)

When separated by commas, the files are compiled separately into multiple object files.

A positional qualifier applies only to the file specification it immediately follows.

Separate compilation by using comma-separated files (or by using multiple FORTRAN commands) prevents certain interprocedure optimizations.

Specify /FLOAT=IEEE_FLOAT on one command line

Specify /FLOAT=G_FLOAT on another command line

Link the resulting object files together into a program

When you run the program, the values returned for floating-point numbers in a COMMON block will be unpredictable. For qualifiers related only to compile-time behavior (such as /LIST and /SHOW), this restriction does not apply.

2.2.3. Creating and Using Module Files

VSI Fortran creates module files for each module declaration and automatically searches for a module file referenced by a USE statement (introduced in Fortran 90). A module file contains the equivalent of the module source declaration in a post-compiled, binary form.

2.2.3.1. Creating Module Files

When you compile a VSI Fortran source file that contains module declarations, VSI Fortran creates a separate file for each module declaration in the current process default device and directory. The name declared in a MODULE statement becomes the base prefix of the file name and is followed by the F90$MOD file type.

MODULE MOD1

The compiler creates a post-compiled module file MOD1.F90$MOD in the current directory. An object file is also created for the module.

Compiling a source file that contains multiple module declarations will create multiple module files, but only a single object file. If you need a separate object file for each module, place only one module declaration in each file.

If a source file does not contain the main program and you need to create module files only, specify the /NOOBJECT qualifier to prevent object file creation.

To specify a directory other than the current directory for the module file(s) to be placed, use the /MODULE qualifier (see Section 2.3.31, ''/MODULE — Placement of Module Files'').

Note that an object file is not needed if there are only INTERFACE or constant (PARAMETER) declarations; however, it is needed for all other types of declarations including variables.

2.2.3.2. Using Module Files

USE MOD1

By default, the compiler searches for a module file named MOD1.F90$MOD in the current directory.

Whether the module files need to be available privately, such as for testing purposes (not shared).

Whether you want the module files to be available to other users on your project or available system-wide (shared).

Whether test builds and final production builds will use the same or a different directory for module files.

You can specify one or more additional directories for the compiler to search by using the /INCLUDE=

directoryqualifier.You can specify one or more additional directories for the compiler to search by defining the logical name FORT$INCLUDE. To search multiple additional directories with FORT$INCLUDE, define it as a search list. Like other logical names, FORT$INCLUDE can be for a system-wide location (such as a group or system logical name) or a private or project location (such as a process, job, or group logical name).

You can prevent the compiler from searching in the directory specified by the FORT$INCLUDE logical name by using the /NOINCLUDE qualifier.

The current process device and directory

Each directory specified by the /INCLUDE qualifier

The directory specified by the logical name FORT$INCLUDE (unless /NOINCLUDE was specified).

You cannot specify a module (.F90$MOD) file directly on the FORTRAN command line.

$FORTRAN PROJ_M.F90 /INCLUDE=(DISKA:[PROJ_MODULE.F90],DISKB:[COMMON.FORT])

If you specify multiple directories with the /INCLUDE qualifier, the order of the directories in the /INCLUDE qualifier determines the directory search order.

Module nesting depth is unlimited. If you will use many modules in a program, check the process and system file limits (see Section 1.2, ''VSI Fortran Programming Environment'').

For More Information:

On the FORTRAN /INCLUDE qualifier, see Section 2.3.25, ''/INCLUDE — Add Directory for INCLUDE and Module File Search''.

On an example program that uses a module, see Section 1.4, ''Creating and Running a Program Using a Module and Separate Function''.

2.2.4. Using Include Files and Include Text Library Modules

You can create include files with a text editor. The include files can be placed in a text library. If needed, you can copy include files or include text library to a shared or private directory.

Whether the include files or text library needs to be available privately, such as for testing purposes (not shared).

Whether you want the files to be available to other users on your project or available system-wide (shared).

Whether test builds and final production builds will use the same or a different directory.

Instead of placing include files in a directory, consider placing them in a text library. The text library can contain multiple include files in a single library file and is maintained by using the OpenVMS LIBRARY command.

2.2.4.1. Using Include Files and INCLUDE Statement Forms

Include files have a file type like other VSI Fortran source files (F90, FOR, or F). Use an INCLUDE statement to request that the specified file containing source lines be included in place of the INCLUDE statement.

INCLUDE 'name' INCLUDE 'name.typ'

You can specify /LIST or /NOLIST after the file name. You can also specify the /SHOW=INCLUDE or /SHOW=NOINCLUDE qualifier to control whether source lines from included files or library modules appear in the listing file (see Section 2.3.43, ''/SHOW — Control Source Content in Listing File'').

INCLUDE '[directory]name' INCLUDE '[directory]name.typ'

If a directory is specified, only the specified directory is searched. The remainder of this section addresses an INCLUDE statement where the directory has not been specified.

You can request that the VSI Fortran compiler search either in the current process default directory or in the directory where the source file resides that references the include file. To do this, specify the /ASSUME=NOSOURCE_INCLUDE (process default directory) or /ASSUME=SOURCE_INCLUDE qualifier (source file directory). The default is /ASSUME=NOSOURCE_INCLUDE.

You can specify one or more additional directories for the compiler to search by using the /INCLUDE=

directoryqualifier.- You can specify one or more additional directories for the compiler to search by defining the logical name FORT$INCLUDE. To search multiple additional directories with FORT$INCLUDE, define it as a search list. Like other logical names, FORT$INCLUDE can be for:

A system-wide location (such as a group or system logical name)

A private or project location (such as a process, job, or group logical name)

You can prevent the compiler from searching in the directory specified by the FORT$INCLUDE logical name by using the /NOINCLUDE qualifier.

The current process default directory or the directory that the source file resides in (depending on whether /ASSUME=SOURCE_INCLUDE was specified)

Each directory specified by the /INCLUDE qualifier

The directory specified by the logical name FORT$INCLUDE (unless /NOINCLUDE was specified).

2.2.4.2. INCLUDE Statement Forms for Including Text Library Modules

VSI Fortran provides certain include library modules in the text library FORSYSDEF.TLB. Users can create a text library and populate it with include library modules (see Section 2.4, ''Creating and Maintaining Text Libraries''). Within a library, text library modules are identified by a library module name (no file type).

INCLUDE '(name)'INCLUDE 'MYLIB(PROJINC)'

Specify only the name of the library module in an INCLUDE statement in your VSI Fortran source program. You use FORTRAN command qualifiers and logical names to control the directory search for the library.

Specify the name of both the library and library module in an INCLUDE statement in your VSI Fortran source program.

When the INCLUDE statement does not specify the library name, you can define a default library by using the logical name FORT$LIBRARY.

When the INCLUDE statement does not specify the library name, you can specify the name of the library using the /LIBRARY qualifier on the FORTRAN command line that you use to compile the source program.

2.2.4.3. Using Include Text Library Modules for a Specified Library Name

When the library is named in the INCLUDE statement, the FORTRAN command searches various directories for the named library, similar to the search for an include file.

You can request that the VSI Fortran compiler search either in the current process default directory or in the directory where the source file resides that references the text library. To do this, specify the /ASSUME=NOSOURCE_INCLUDE (process default directory) or /ASSUME=SOURCE_INCLUDE qualifier (source file directory).

You can specify one or more additional directories for the compiler to search by using the /INCLUDE=

directoryqualifier.- You can specify one or more additional directories for the compile to search by defining the logical name FORT$INCLUDE. To search multiple additional directories with FORT$INCLUDE, define it as a search list. Like other logical names, FORT$INCLUDE can be for:

A system-wide location (such as a group or system logical name)

A private or project location (such as a process, job, or group logical name)

You can prevent the compiler from searching in the directory specified by the FORT$INCLUDE logical name by using the /NOINCLUDE qualifier.

The current process default directory or the directory that the source file resides in (depending on whether /ASSUME=SOURCE_INCLUDE was specified)

Each directory specified by the /INCLUDE qualifier

The directory specified by the logical name FORT$INCLUDE (unless /NOINCLUDE was specified).

INCLUDE 'PROJLIB(MYINC)/LIST'

You can also specify the /SHOW=INCLUDE or /SHOW=NOINCLUDE qualifier to control whether source lines from included files or library modules appear in the listing file (see Section 2.3.43, ''/SHOW — Control Source Content in Listing File'').

For More Information:

On the /ASSUME=[NO]SOURCE_INCLUDE qualifier, see Section 2.3.7, ''/ASSUME — Compiler Assumptions''.

On the /INCLUDE qualifier, see Section 2.3.25, ''/INCLUDE — Add Directory for INCLUDE and Module File Search''.

On creating and using text libraries, see Section 2.4, ''Creating and Maintaining Text Libraries''.

2.2.4.4. Using Include Text Library Modules for an Unspecified Library Name

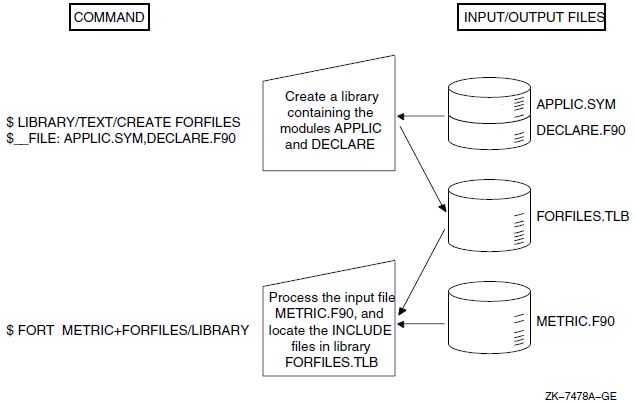

Specify the library name on the FORTRAN command line, appended with the /LIBRARY positional qualifier. The /LIBRARY qualifier identifies a file specification as a text library.

Concatenate the name of the text library to the name of the source file and append the /LIBRARY qualifier to the text library name (use the plus sign (+)) separator. For example:$FORTRAN APPLIC+DATAB/LIBRARYWhenever an INCLUDE statement occurs in APPLIC.FOR, the compiler searches the library DATAB.TLB for the source text module identified in the INCLUDE statement and incorporates it into the compilation.

When more than one library is specified on a FORTRAN command line, the VSI Fortran compiler searches the libraries each time it processes an INCLUDE statement that specifies a text module name. The compiler searches the libraries in the order specified on the command line. For example:$FORTRAN APPLIC+DATAB/LIBRARY+NAMES/LIBRARY+GLOBALSYMS/LIBRARYWhen the VSI Fortran compiler processes an INCLUDE statement in the source file APPLIC.FOR, it searches the libraries DATAB.TLB, NAMES.TLB, and GLOBALSYMS.TLB, in that order, for source text modules identified in the INCLUDE statement.

When the FORTRAN command requests multiple compilations, a library must be specified for each compilation in which it is needed. For example:$FORTRAN METRIC+DATAB/LIBRARY, APPLIC+DATAB/LIBRARYIn this example, VSI Fortran compiles METRIC.FOR and APPLIC.FOR separately and uses the library DATAB.TLB for each compilation.

If the text library is not in the current process default directory, specify the device and/or directory. For example:$FORTRAN PROJ_MAIN+$DISK2:[PROJ.LIBS]COMMON_LIB/LIBRARYInstead of specifying the device and directory name, you can use the /ASSUME=SOURCE_INCLUDE and /INCLUDE qualifiers and FORT$INCLUDE logical name to control the directory search.

After the compiler has searched all libraries specified on the command line, it searches the default user library (if any) specified by the logical name FORT$LIBRARY. When you want to define one of your private text libraries as a default library for the VSI Fortran compiler to search, consider using the FORT$LIBRARY logical name.

For example, define a default library using the logical name FORT$LIBRARY before compilation, as in the following example of the DCL command DEFINE:$DEFINE FORT$LIBRARY $DISK2:[LIB]DATAB$FORTRAN PROJ_MAINWhile this assignment is in effect, the compiler automatically searches the library $DISK2:[LIB]DATAB.TLB for any include library modules that it cannot locate in libraries explicitly specified, if any, on the FORTRAN command line.

You can define the logical name FORT$LIBRARY in any logical name table defined in the logical name table search list LMN$FILE_DEV. For example:$DEFINE /GROUP FORT$LIBRARY $DISK2:[PROJ.LIBS]APPLIB.TLB$FORTRAN PROJ_MAINIf the name is defined in more than one table, the VSI Fortran compiler uses the equivalence for the first match it finds in the normal order of search – first the process table, then intermediate tables (job, group, and so on), and finally the system table. If the same logical name is defined in both the process and system logical name tables, the process logical name table assignment overrides the system logical name table assignment.

If FORT$LIBRARY is defined as a search list, the compiler opens the first text library specified in the list. If the include library module is not found in that text library, the search is terminated and an error message is issued.

The logical name FORT$LIBRARY is recognized by both Compaq Fortran 77 and VSI Fortran.

When the VSI Fortran compiler cannot find the include library modules in libraries specified on the FORTRAN command line or in the default library defined by FORT$LIBRARY, it then searches the standard text library supplied by VSI Fortran. This library resides in SYS$LIBRARY with a file name of FORSYSDEF.TLB and simplifies calling OpenVMS system services.

SYS$LIBRARY identifies the device and directory containing system libraries and is normally defined by the system manager. FORSYSDEF.TLB is a library of include library modules supplied by VSI Fortran. It contains local symbol definitions and structures required for use with system services and return status values from system services.

For more information on the contents of FORSYSDEF, see Appendix E, "Contents of the VSI Fortran System Library FORSYSDEF".

INCLUDE '(MYINC)/NOLIST'

You can also specify the /SHOW=INCLUDE or /SHOW=NOINCLUDE qualifier to control whether source lines from included files or library modules appear in the listing file (see Section 2.3.43, ''/SHOW — Control Source Content in Listing File'').

For More Information:

On the /ASSUME=[NO]SOURCE_INCLUDE qualifier, see Section 2.3.7, ''/ASSUME — Compiler Assumptions''.

On the /INCLUDE qualifier, see Section 2.3.25, ''/INCLUDE — Add Directory for INCLUDE and Module File Search''.

On creating and using text libraries, see Section 2.4, ''Creating and Maintaining Text Libraries''.

2.2.5. Specifying Output Files

The output produced by the compiler includes the object and listing files. You can control the production of these files by using the appropriate qualifiers on the FORTRAN command line.

For command procedures that compile the application in either batch or interactive mode, consider explicitly specifying /NOLIST (or /LIST).

If you specify one source file, one object file is generated.

If you specify multiple source files separated by commas, each source file is compiled separately, and an object file is generated for each source file.

If you specify multiple source files separated by plus signs, the source files are concatenated and compiled, and one object file is generated.

You can use both commas and plus signs in the same command line to produce different combinations of concatenated and separate object files (see the examples of the FORTRAN command at the end of this section).

Otherwise, the object file has the file name of its corresponding source file and a file type of OBJ.To name an object file, use the /OBJECT qualifier in the form /OBJECT= file-spec.By default, the object file produced from concatenated source files has the name of the first source file. All other file specification fields (node, device, directory, and version) assume the default values.

When creating object files that will be placed in an object library, consider using the /SEPARATE_COMPILATION qualifier, which places individual compilation units in a source file as separate components in the object file. This minimizes the size of the routines included by the linker as it creates the executable image. However, to allow more interprocedure optimizations, use the default /NOSEPARATE_COMPILATION.

For More Information:

On creating and naming object files, see Section 2.2.6.1, ''Naming the Object File'' and Section 2.3.33, ''/OBJECT — Specify Name or Prevent Object File Creation''.

On the /SEPARATE_COMPILATION qualifier, see Section 2.3.41, ''/SEPARATE_COMPILATION — Control Compilation Unit Use in Object Files''.

On using object libraries, see Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs".

2.2.6. Examples of the FORTRAN Command

The following examples show the use of the FORTRAN command.

2.2.6.1. Naming the Object File

$FORTRAN /OBJECT=[BUILD]SQUARE /NOLISTReturn_File:CIRCLE

The source file CIRCLE.F90 is compiled, producing an object file named SQUARE.OBJ in the [BUILD] directory, but no listing file.

2.2.6.2. Compiler Source Checking Only (No Object File)

$FORTRAN /NOOBJECT ABC.FOR

The source file ABC.FOR is compiled, syntax checking occurs, but no object file is produced. The /NOOBJECT qualifier performs full compilation checking without creating an object file.

2.2.6.3. Requesting a Listing File and Contents

$FORTRAN /LIST /SHOW=INCLUDE /MACHINE_CODE XYZ.F90

The source file XYZ.F90 is compiled, and the listing file XYZ.LIS and object file XYZ.OBJ are created. The listing file contains the optional included source files (/SHOW=INCLUDE) and machine code representation (/MACHINE_CODE).

The default is /NOLIST for interactive use and /LIST for batch use, so consider explicitly specifying either /LIST or /NOLIST.

2.2.6.4. Compiling Multiple Files

$FORTRAN/LIST AAA.F90, BBB.F90, CCC.F90

Object files named AAA.OBJ, BBB.OBJ, and CCC.OBJ

Listing files named AAA.LIS, BBB.LIS, and CCC.LIS

The default level of optimization is used (/OPTIMIZE=LEVEL=4), but interprocedure optimizations are less effective because the source files are compiled separately.

$FORTRAN XXX.FOR+YYY.FOR+ZZZ.FOR

Source files XXX.FOR, YYY.FOR, and ZZZ.FOR are concatenated and compiled as one file, producing an object file named XXX.OBJ. The default level of optimization is used, allowing interprocedure optimizations since the files are compiled together (see Section 5.1.2, ''Compile Using Multiple Source Files and Appropriate FORTRAN Qualifiers''). In interactive mode, no listing file is created; in batch mode, a listing file named XXX.LIS would be created.

$FORTRAN AAA+BBB,CCC/LIST

Two object files are produced: AAA.OBJ (comprising AAA.F90 and BBB.F90) and CCC.OBJ (comprising CCC.F90). One listing file is produced: CCC.LIS (comprising CCC.F90), since the positional /LIST qualifier follows a specific file name (and not the FORTRAN command). Because the default level of optimization is used, interprocedure optimizations for both AAA.F90 and BBB.F90 occur. Only interprocedure optimizations within CCC.F90 occur.

$FORTRAN ABC+CIRC/NOOBJECT+XYZ

The /NOOBJECT qualifier applies to all files in the concatenated file list and suppresses object file creation. Source files ABC.F90, CIRC.F90, and XYZ.F90 are concatenated and compiled, but no object file is produced.

2.2.6.5. Requesting Additional Compile-Time and Run-Time Checking

$FORTRAN /WARNINGS=ALL /CHECK=ALL TEST.F90

This command creates the object file TEST.OBJ and can result in more informational or warning compilation messages than the default level of warning messages. Additional run-time messages can also occur.

2.2.6.6. Checking Fortran 90 or 95 Standard Conformance

$FORTRAN /STANDARD=F90 /NOOBJECT PROJ_STAND.F90

This command does not create an object file but issues additional compilation messages about the use of any nonstandard extensions to the Fortran 90 standard it detects.

To check for Fortran 95 standard conformance, specify /STANDARD=F95 instead of /STANDARD=F90.

2.2.6.7. Requesting Additional Optimizations

$FORTRAN /OPTIMIZE=(LEVEL=5,UNROLL=3) M_APP.F90+SUB.F90/NOLIST

The source files are compiled together, producing an object file named M_APP.OBJ. The software pipelining optimization (/OPTIMIZE=LEVEL=4) is requested. Loops within the program are unrolled three times (UNROLL=3). Loop unrolling occurs at optimization level three (LEVEL=3) or above.

For More Information:

On linking object modules into an executable image (program) and running the program, see Chapter 3, "Linking and Running VSI Fortran Programs".

On requesting debugger symbol table information, see Section 4.2.1, ''Compiling and Linking a Program to Prepare for Debugging''.

On requesting additional directories to be searched for module files or included source files, see Section 2.3.25, ''/INCLUDE — Add Directory for INCLUDE and Module File Search'' and Section 2.4, ''Creating and Maintaining Text Libraries''.

On the FORTRAN command qualifiers, see Section 2.3, ''FORTRAN Command Qualifiers ''.

2.3. FORTRAN Command Qualifiers

FORTRAN command qualifiers influence the way in which the compiler processes a file. In some cases, the simple FORTRAN command is sufficient. Use optional qualifiers when needed.

You can override some qualifiers specified on the command line by using the OPTIONS statement. The qualifiers specified by the OPTIONS statement affect only the program unit where the statement occurs. For more information about the OPTIONS statement, see the VSI Fortran Reference Manual.

2.3.1. FORTRAN Command Qualifier Syntax

$FORTRAN /ALIG=NAT /LIS EXTRAPOLATE.FOR

When creating command procedures, avoid using abbreviations for qualifiers and their keywords. VSI Fortran might add new qualifiers and keywords for a subsequent release that makes an abbreviated qualifier and keyword nonunique in a subsequent release.

$FORTRAN /WARN=(ALIGN, DECLARATION) EXTRAPOLATE.FOR

To concatenate source files, separate file names with a plus sign (+) instead of a comma (,). (See Section 2.2.2, ''Specifying Multiple Input Files '').

2.3.2. Summary of FORTRAN Command Qualifiers

Table 2.1, ''FORTRAN Command Qualifiers'' lists the FORTRAN Command qualifiers, including their default values.

|

Qualifiers and Defaults | |

|---|---|

|

/ALIGNMENT or /NOALIGNMENT or

/ALIGNMENT= {

rule

|

class =

rule

| ( class =

rule [, ...]) | [NO]SEQUENCE | ALL (or NATURAL) | NONE (or PACKED) } where:

class = { COMMONS | RECORDS | STRUCTURES } Default: /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(PACKED ?, NOMULTILANGUAGE), NOSEQUENCE?, RECORDS=NATURAL) | |

|

/ANALYSIS_DATA[= filename] or /NOANALYSIS_DATA Default: /NOANALYSIS_DATA | |

|

/ANNOTATIONS or /NOANNOTATIONS or

/ANNOTATIONS= {

{ CODE | DETAIL | INLINING | LOOP_TRANSFORMS | LOOP_UNROLLING | PREFETCHING | SHRINKWRAPPING | SOFTWARE_PIPELINING | TAIL_CALLS | TAIL_RECURSION } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE }

} Default: /NOANNOTATIONS | |

/ARCHITECTURE= { GENERIC | HOST | EV4 | EV5 | EV56 | PCA56 | EV6 | EV67 } Default: /ARCHITECTURE=GENERIC? | |

|

/NOASSUME or

/ASSUME= {

{ [NO]ACCURACY_SENSITIVE | [NO]ALTPARAM | [NO]BUFFERED_IO | [NO]BYTERECL | [NO]DUMMY_ALIASES | [NO]FP_CONSTANT | [NO]INT_CONSTANT | [NO]MINUS0 | [NO]PROTECT_CONSTANTS | [NO]SOURCE_INCLUDE } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE }

} Default: /ASSUME= (ACCURACY_SENSITIVE?, ALTPARAM, NOBUFFERED_IO, NOBYTERECL, NODUMMY_ALIASES, NOFP_CONSTANT, NOINT_CONSTANT, NOMINUS0, PROTECT_CONSTANTS, NOSOURCE_INCLUDE) | |

|

/AUTOMATIC or /NOAUTOMATIC Default: /NOAUTOMATIC | |

|

/BY_REF_CALL=( No default | |

|

/CCDEFAULT or

/CCDEFAULT= {

{ FORTRAN | LIST | NONE | DEFAULT }

} Default: /CCDEFAULT=DEFAULT | |

|

/NOCHECK or

/CHECK= { { [NO]ARG_INFO (I64 only) | [NO]ARG_TEMP_CREATED | [NO]BOUNDS | [NO]FORMAT | [NO]FP_EXCEPTIONS | [NO]FP_MODE (I64 only) | [NO]OUTPUT_CONVERSION | [NO]OVERFLOW | [NO]POWER | [NO]UNDERFLOW } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE } } Default: /CHECK= ( NOBOUNDS, FORMAT?, NOFP_EXCEPTIONS, OUTPUT_CONVERSION?, NOOVERFLOW, POWER, NOUNDERFLOW) | |

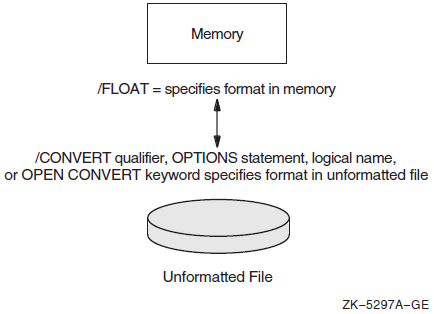

/CONVERT= { BIG_ENDIAN | CRAY | FDX | FGX | IBM | LITTLE_ENDIAN | NATIVE | VAXD | VAXG } Default: /CONVERT=NATIVE | |

|

/D_LINES or /NOD_LINES Default: /NOD_LINES | |

|

/DEBUG or /NODEBUG or

/DEBUG= { { [NO]SYMBOLS | [NO]TRACEBACK } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE } } Default: /DEBUG= (NOSYMBOLS, TRACEBACK) | |

|

/DIAGNOSTICS[= filename] or /NODIAGNOSTICS Default: /NODIAGNOSTICS | |

|

/DML Default is omitted | |

/DOUBLE_SIZE= { 64 | 128 } Default: /DOUBLE_SIZE=64 | |

|

/ERROR_LIMIT= Default: /ERROR_LIMIT=30 | |

|

/EXTEND_SOURCE or /NOEXTEND_SOURCE Default: /NOEXTEND_SOURCE | |

|

/F77 or /NOF77 Default: /F77 | |

|

/FAST No default | |

/FLOAT= { D_FLOAT | G_FLOAT | IEEE_FLOAT } Defaults: /FLOAT=IEEE (I64) /FLOAT=G_FLOAT (Alpha)? | |

/GRANULARITY= { BYTE | LONGWORD | QUADWORD } Default: /GRANULARITY=QUADWORD | |

/IEEE_MODE= { FAST | UNDERFLOW_TO_ZERO | DENORM_RESULTS } Default: /IEEE_MODE=DENORM_RESULTS (I64) Default: /IEEE_MODE=FAST (Alpha) | |

|

/INCLUDE= Default: /NOINCLUDE | |

/INTEGER_SIZE= { 16 | 32 | 64 } Default: INTEGER_SIZE=32? | |

|

/LIBRARY No default | |

|

/LIST[= file-spec] or /NOLIST Defaults: /NOLIST (interactive) /LIST (batch ) | |

|

/MACHINE_CODE or /NOMACHINE_CODE /NOMACHINE_CODE | |

/MATH_LIBRARY= { ACCURATE | FAST } Default: /MATH_LIBRARY=ACCURATE? | |

|

/MODULE= directory or /NOMODULE Default: /NOMODULE | |

/NAMES= { UPPERCASE | LOWERCASE | AS_IS } Default: /NAMES=UPPERCASE | |

|

/OBJECT[= file-spec] or /NOOBJECT Default: /OBJECT | |

|

/OLD_F77 (Alpha only) Omitted | |

|

/OPTIMIZE or /NOOPTIMIZE or /OPTIMIZE= { LEVEL= n | INLINE= { NONE | MANUAL | SIZE | SPEED | ALL }

| NOINLINE | LOOPS | PIPELINE | TUNE= { GENERIC | HOST | EV4 | EV5 | EV56 | PCA56 | EV6 | EV67 }

| UNROLL= n } [, ...] Default: /OPTIMIZE (same as /OPTIMIZE= (LEVEL=4, INLINE=SPEED, NOLOOPS, NOPIPELINE, TUNE=GENERIC?, UNROLL=0)) | |

|

/PAD_SOURCE or /NOPAD_SOURCE Default: /NOPAD_SOURCE | |

/REAL_SIZE= { 32 | 64 | 128 } Default: /REAL_SIZE=32 | |

|

/RECURSIVE or /NORECURSIVE Default: /NORECURSIVE | |

|

/NOREENTRANCY or

/REENTRANCY= { ASYNC | NONE | THREADED } Default: /REENTRANCY=NONE | |

/ROUNDING_MODE= { NEAREST | CHOPPED | DYNAMIC | MINUS_INFINITY } Default: /ROUNDING_MODE=NEAREST | |

|

/SEPARATE_COMPILATION or /NOSEPARATE_COMPILATION Default: /NOSEPARATE_COMPILATION | |

/SEVERITY=WARNINGS= { WARNING | ERROR | STDERROR } Default: /SEVERITY=WARNINGS=(WARNING) | |

|

/SHOW or /NOSHOW or

/SHOW= {

{ [NO]DICTIONARY | [NO]INCLUDE | [NO]MAP | [NO]PREPROCESSOR } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE }

} Default: /SHOW= (NODICTIONARY, NOINCLUDE, MAP, NOPREPROCESSOR ) | |

/SOURCE_FORM= { FREE | FIXED } Default: Depends on file type (F90 for free form and FOR or F for fixed form) | |

/STANDARD= { F90 | F95 } Default: /NOSTANDARD | |

|

/SYNCHRONOUS_EXCEPTIONS or /NOSYNCHRONOUS_EXCEPTIONS (Alpha only) Default: /NOSYNCHRONOUS_EXCEPTIONS | |

|

/SYNTAX_ONLY or /NOSYNTAX_ONLY Default: /NOSYNTAX_ONLY | |

|

/TIE or /NOTIE Default: /NOTIE | |

|

/VERSION Default is omitted | |

|

/VMS or /NOVMS Default: /VMS | |

|

/WARNINGS or /NOWARNINGS or

/WARNINGS= {

{ [NO]ALIGNMENT | [NO]ARGUMENT_CHECKING | [NO]DECLARATIONS | [NO]GENERAL | [NO]GRANULARITY | [NO]IGNORE_LOC | [NO]TRUNCATED_SOURCE | [NO]UNCALLED | [NO]UNINITIALIZED | [NO]UNUSED | [NO]USAGE } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE }

} Default: /WARNINGS= (ALIGNMENT, NOARGUMENT_CHECKING, NODECLARATIONS, GENERAL, GRANULARITY, NOIGNORE_LOC, NOTRUNCATED_SOURCE, UNCALLED, UNINITIALIZED, NOUNUSED, USAGE ) |

2.3.3. /ALIGNMENT — Data Alignment

The /ALIGNMENT qualifier controls the data alignment of numeric fields in common blocks and structures.

Individual data items (not part of a common block or other structure) are naturally aligned.

Fields in derived-type (user-defined) structures (where the SEQUENCE statement is omitted) are naturally aligned.

Fields in Compaq Fortran 77 record structures are naturally aligned.

Data items in common blocks are not naturally aligned, unless data declaration order has been planned and checked to ensure that all data items are naturally aligned.

Although VSI Fortran always aligns local data items on natural boundaries, certain data declaration statements and unaligned arguments can force unaligned data.

Use the /ALIGNMENT qualifier to control the alignment of fields associated with common blocks, derived-type structures, and record structures.

Note

Unaligned data significantly increases the time it takes to execute a program, depending on the number of unaligned fields encountered. Specifying /ALIGNMENT=ALL (same as /ALIGNMENT=NATURAL) minimizes unaligned data.

The qualifier has the following form:

/ALIGNMENT= {

rule

|

class = rule

| (class = rule

[, ...]) | [NO]SEQUENCE | ALL (or NATURAL) | NONE (or PACKED) } where:

class= { COMMONS | RECORDS | STRUCTURES } and

rule= { NATURAL | PACKED | STANDARD | [NO]MULTILANGUAGE } STANDARD and MULTILANGUAGE are valid for class=COMMON (not

class=RECORDS).

The /ALIGNMENT qualifier keywords specify whether the VSI Fortran compiler should naturally align or arbitrarily pack the following:

class COMMONS= rule applies to common blocks (COMMON statement); rule can be PACKED, STANDARD, NATURAL, or MULTILANGUAGE.

RECORDS= rule applies to derived-type and record structures; rule can be PACKED or NATURAL. However, if a derived-type data definition specifies the SEQUENCE statement, the FORTRAN /ALIGNMENT qualifier has no effect on unaligned data, so data declaration order must be carefully planned to naturally align data.

STRUCTURES= rule applies to derived-type and record structures; rule can be PACKED or NATURAL. For the VSI Fortran language, STRUCTURES and RECORDS are the same (they may have a different meaning in other OpenVMS languages).

rule NATURAL requests that fields in derived-type and record structures and data items in common blocks be naturally aligned on up to 8-byte boundaries, including INTEGER (KIND=8) and REAL (KIND=8) data.

Specifying /ALIGNMENT=NATURAL is equivalent to any of the following:/ALIGNMENT /ALIGNMENT=ALL /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(NATURAL,NOMULTILANGUAGE),RECORDS=NATURAL,SEQUENCE)

PACKED requests that fields in derived-type and record structures and data items in common blocks be packed on arbitrary byte boundaries and not naturally aligned.

Specifying /ALIGNMENT=PACKED is equivalent to any of the following:/ALIGNMENT=NONE /NOALIGNMENT /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(PACKED,NOMULTILANGUAGE),RECORDS=PACKED,NOSEQUENCE)

STANDARD specifies that data items in common blocks will be naturally aligned on up to 4-byte boundaries (consistent with the FORTRAN-77, Fortran 90, and Fortran 95 standards).

The compiler will not naturally align INTEGER (KIND=8) and REAL (KIND=8) data declarations. Such data declarations should be planned so they fall on natural boundaries. Specifying /ALIGNMENT=/ALIGNMENT=COMMONS=STANDARD alone is the same as /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(STANDARD,NOMULTILANGUAGE),RECORDS=NATURAL).

You cannot specify /ALIGNMENT=RECORDS=STANDARD or /ALIGNMENT=STANDARD.

MULTILANGUAGE specifies that the compiler pad the size of common block program sections to ensure compatibility when the common block program section is shared by code created by other OpenVMS compilers.

When a program section generated by a Fortran common block is overlaid with a program section consisting of a C structure, linker error messages can result. This is because the sizes of the program sections are inconsistent; the C structure is padded and the Fortran common block is not.

Specifying /ALIGNMENT=COMMONS=MULTILANGUAGE ensures that VSI Fortran follows a consistent program section size allocation scheme that works with VSI C program sections that are shared across multiple images. Program sections shared in a single image do not have a problem. The equivalent VSI C qualifier is /PSECT_MODEL=[NO]MULTILANGUAGE.

The default is /ALIGNMENT=COMMONS=NOMULTILANGUAGE, which also is the default behavior of Compaq Fortran 77 and is sufficient for most applications.

The [NO]MULTILANGUAGE keyword only applies to common blocks. You can specify /ALIGNMENT=COMMONS=[NO]MULTILANGUAGE, but you cannot specify /ALIGNMENT=[NO]MULTILANGUAGE.

[NO]SEQUENCE Specifying /ALIGNMENT=SEQUENCE means that components of derived types with the SEQUENCE attribute will obey whatever alignment rules are currently in use. The default alignment rules align components on natural boundaries.

The default value of /ALIGNMENT=NOSEQUENCE means that components of derived types with the SEQUENCE attribute will be packed, regardless of whatever alignment rules are currently in use.

Specifying /FAST sets /ALIGNMENT=SEQUENCE so that components of derived types with the SEQUENCE attribute will be naturally aligned for improved performance. Specifying /ALIGNMENT=ALL also sets /ALIGNMENT=SEQUENCE.

ALL Specifying /ALIGNMENT=ALL is equivalent to /ALIGNMENT, /ALIGNMENT=NATURAL), or /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS= (NATURAL,NOMULTILANGUAGE),RECORDS=NATURAL,SEQUENCE).

NONE Specifying /ALIGNMENT=NONE is equivalent to /NOALIGNMENT, /ALIGNMENT=PACKED, or /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(PACKED, NOMULTILANGUAGE), RECORDS=PACKED,NOSEQUENCE).

|

Command Line |

Default |

|---|---|

|

Omit /ALIGNMENT and omit /FAST | /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=(PACKED, NOMULTILANGUAGE),NOSEQUENCE, RECORDS=NATURAL) |

|

Omit /ALIGNMENT and specify /FAST | /ALIGNMENT=(COMMONS=NATURAL, RECORDS=NATURAL,SEQUENCE) |

|

/ALIGNMENT=COMMONS= rule | Use whatever the /ALIGNMENT qualifier specifiers for COMMONS, but use the default of RECORDS=NATURAL |

|

/ALIGNMENT=RECORDS= rule | Use whatever the /ALIGNMENT qualifier specifies for RECORDS, but use the default for COMMONS (depends on whether /FAST was specified or omitted) |

You can override the alignment specified on the command line by using a cDEC$ OPTIONS directive, as described in the VSI Fortran Reference Manual.

The /ALIGNMENT and /WARNINGS=ALIGNMENT qualifiers can be used together in the same command line.

For More Information:

On run-time performance guidelines, see Chapter 5, "Performance: Making Programs Run Faster".

On data alignment, see Section 5.3, ''Data Alignment Considerations''.

On checking for alignment traps with a condition handler, see Section 14.12, ''Checking for Data Alignment Traps''.

On intrinsic data sizes, see Chapter 8, "Data Types and Representation".

On the /FAST qualifier, see Section 2.3.21, ''/FAST — Request Fast Run-Time Performance''.

2.3.4. /ANALYSIS_DATA – Create Analysis Data File

The /ANALYSIS_DATA qualifier produces an analysis data file that contains cross-reference and static-analysis information about the source code being compiled. The Fortran compiler produces limited Source Code Analyzer (SCA) information about the source program. The Fortran 95 compiler only produces basic SCA information about modules. It does not include information about variables and other symbols.

Analysis data files are reserved for use by products such as, but not limited to, the Source Code Analyzer.

/ANALYSIS_DATA[=filename.type]If you omit the file specification, the analysis file name has the name of the primary source file and a file type of ANA ( filename.ANA).

The compiler produces one analysis file for each source file that it compiles. If you are compiling multiple files and you specify a particular name as the name of the analysis file, each analysis file is given that name (with an incremental version number).

If you do not specify the /ANALYSIS_DATA qualifier, the default is /NOANALYSIS_DATA.

2.3.5. /ANNOTATIONS — Code Descriptions

The /ANNOTATIONS qualifier controls whether an annotated listing showing optimizations is included with the listing file.

The qualifier has the following form:

/ANNOTATIONS= { { CODE | DETAIL | INLINING | LOOP_TRANSFORMS | LOOP_UNROLLING | PREFETCHING | SHRINKWRAPPING | SOFTWARE_PIPELINING | TAIL_CALLS | TAIL_RECURSION } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE } } CODE Annotates the machine code listing with descriptions of special instructions used for prefetching, alignment, and so on.

DETAIL Provides additional level of annotation detail, where available.

INLINING Indicates where code for a called procedure was expanded inline.

LOOP_TRANSFORMS Indicates where advanced loop nest optimizations have been applied to improve cache performance.

LOOP_UNROLLING Indicates where a loop was unrolled (contents expanded multiple times).

PREFETCHING Indicates where special instructions were used to reduce memory latency.

SHRINKWRAPPING Indicates removal of code establishing routine context when it is not needed.

SOFTWARE_PIPELINING Indicates where instructions have been rearranged to make optimal use of the processor's functional units.

TAIL_CALLS Indicates an optimization where a call can be replaced with a jump.

TAIL_RECURSION Indicates an optimization that eliminates unnecessary routine context for a recursive call.

ALL All annotations, including DETAIL, are selected. This is the default if no keyword is specified.

NONE No annotations are selected. This is the same as /NOANNOTATIONS.

2.3.6. /ARCHITECTURE — Architecture Code Instructions (Alpha only)

The /ARCHITECTURE qualifier specifies the type of Alpha architecture code instructions generated for a particular program unit being compiled; it uses the same options (keywords) as used by the /OPTIMIZE=TUNE (Alpha only) qualifier (for instruction scheduling purposes).

OpenVMS Version 7.1 and subsequent releases provide an operating system kernel that includes an instruction emulator. This emulator allows new instructions, not implemented on the host processor chip, to execute and produce correct results. Applications using emulated instructions will run correctly but may incur significant software emulation overhead at runtime.

All Alpha processors implement a core set of instructions. Certain Alpha processor versions include additional instruction extensions.

The qualifier has the following form:

/ARCHITECTURE= { GENERIC | HOST | EV4 | EV5 | EV56 | PCA56 | EV6 | EV67 } GENERIC Generates code that is appropriate for all Alpha processor generations. This is the default.

Programs compiled with the GENERIC option run on all implementations of the Alpha architecture without any instruction emulation overhead.

HOST Generates code for the processor generation in use on the system being used for compilation.

Programs compiled with this option may encounter instruction emulation overhead if run on other implementations of the Alpha architecture.

EV4 Generates code for the 21064, 21064A, 21066, and 21068 implementations of the Alpha architecture. Programs compiled with the EV4 option run on all Alpha processors without instruction emulation overhead.

EV5 Generates code for some 21164 chip implementations of the Alpha architecture that use only the base set of Alpha instructions (no extensions). Programs compiled with the EV5 option run on all Alpha processors without instruction emulation overhead.

EV56 Generates code for some 21164 chip implementations that use the BWX (Byte/Word manipulation) instruction extensions of the Alpha architecture.

Programs compiled with the EV56 option may incur emulation overhead on EV4 and EV5 processors but still run correctly on OpenVMS Version 7.1 (or later) systems.

PCA56 Generates code for the 21164PC chip implementation that uses the BWX (Byte/Word manipulation) and MAX (Multimedia) instruction extensions of the Alpha architecture.

Programs compiled with the PCA56 option may incur emulation overhead on EV4, EV5, and EV56 processors but will still run correctly on OpenVMS Version 7.1 (or later) systems.

EV6 Generates code for the 21264 chip implementation that uses the following extensions to the base Alpha instruction set: BWX (Byte/Word manipulation) and MAX (Multimedia) instructions, square root and floating-point convert instructions, and count instructions.

Programs compiled with the EV6 option may incur emulation overhead on EV4, EV5, EV56, and PCA56 processors but will still run correctly on OpenVMS Version 7.1 (or later) systems.

EV67 Generates code for chip implementations that use advanced instruction extensions of the Alpha architecture. This option permits the compiler to generate any EV67 instruction, including the following extensions to the base Alpha instruction set: BWX (Byte/Word manipulation), MVI (Multimedia) instructions, square root and floating-point convert extensions (FIX), and count extensions (CIX).

Programs compiled with the EV67 keyword might incur emulation overhead on EV4, EV5, EV56, PCA56, and EV6 processors but still run correctly on OpenVMS Alpha systems.

2.3.7. /ASSUME — Compiler Assumptions

Whether the compiler should use certain code transformations that affect floating-point operations. These changes may affect the accuracy of the program's results.

What the compiler can assume about program behavior without affecting correct results when it optimizes code.

Whether a single-precision constant assigned to a double-precision variable should be evaluated in single or double precision.

Changes the directory where the compiler searches for files specified by an INCLUDE statement to the directory where the source files reside, not the current default directory.

The qualifier has the following form:

/ASSUME= { { [NO]ACCURACY_SENSITIVE | [NO]ALTPARAM | [NO]BUFFERED_IO | [NO]BYTERECL | [NO]DUMMY_ALIASES | [NO]FP_CONSTANT | [NO]INT_CONSTANT | [NO]MINUS0 | [NO]PROTECT_CONSTANTS | [NO]SOURCE_INCLUDE } [, ...] |

{ ALL | NONE } } [NO]ACCURACY_SENSITIVE If you use ACCURACY_SENSITIVE (the default unless you specified /FAST), the compiler uses a limited number of rules for calculations, which might prevent some optimizations.

Specifying NOACCURACY_SENSITIVE allows the compiler to reorder code based on algebraic identities (inverses, associativity, and distribution) to improve performance. The numeric results can be slightly different from the default (ACCURACY_SENSITIVE) because of the way intermediate results are rounded. Specifying the /FAST qualifier (described in Section 2.3.21, ''/FAST — Request Fast Run-Time Performance'' ) changes the default to NOACCURACY_SENSITIVE.

Numeric results with NOACCURACY_SENSITIVE are not categorically less accurate. They can produce more accurate results for certain floating-point calculations, such as dot product summations.

X = (A + B) - C X = A + (B - C)

Optimizations that result in calls to a special reciprocal square root routine for expressions of the form 1.0/SQRT(x) or A/SQRT(B) are enabled only if /ASSUME=NOACCURACY_SENSITIVE is in effect.