VSI OpenVMS Debugger Manual

- Operating System and Version:

- VSI OpenVMS IA-64 Version 8.4-1H1 or higher

VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 or higher

Preface

1. About VSI

VMS Software, Inc. (VSI) is an independent software company licensed by Hewlett Packard Enterprise to develop and support the OpenVMS operating system.

2. Intended Audience

This manual is for programmers at all levels of experience. It covers all user interfaces of the OpenVMS Debugger:

The command interface for terminals and workstations

The VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface for workstations

The Microsoft Windows PC client interface

The OpenVMS Debugger on OpenVMS Alpha systems can access all the extended memory made available by the 64-bit processing of the OpenVMS Alpha operating system. Hence, you can examine and manipulate data in the complete 64-bit address space.

The OpenVMS Debugger has been internationalized. For Asian users, the debugger's VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS, command line, and screen mode user interfaces can be used with multibyte characters.

You can use the debugger to debug code only in user mode. You cannot debug code in supervisor, executive, or kernel modes.

3. Document Structure

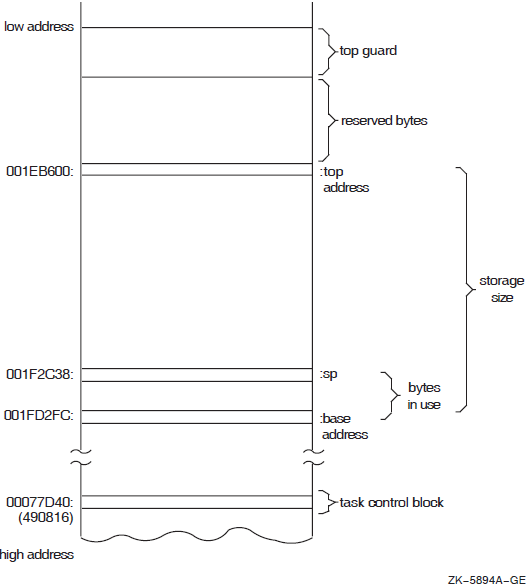

This manual is organized as follows:

- Part I introduces the OpenVMS Debugger. Part I contains one chapter:

Chapter 1, "Introduction to the Debugger " introduces the debugger.

- Part II describes the debugger's command interface. Part II includes the following chapters:

Chapter 2, "Getting Started with the Debugger " gets you started using the debugger.

Chapter 3, "Controlling and Monitoring Program Execution" explains how to control and monitor program execution.

Chapter 4, "Examining and Manipulating Program Data" explains how to examine and manipulate program data.

Chapter 5, "Controlling Access to Symbols in Your Program" explains how to control access to symbols in your program.

Chapter 6, "Controlling the Display of Source Code" explains how to control the display of source code.

Chapter 7, "Screen Mode" explains how to use screen mode.

- Part III describes the debugger's VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface. Part III includes the following chapters:

Chapter 8, "Introduction " gives an overview of its VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface features.

Chapter 9, "Starting and Ending a Debugging Session" explains how to prepare your program for debugging and then start and end a debugging session using the VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface.

Chapter 10, "Using the Debugger", which is organized by task, explains how to use the debugger via the VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface.

- Part IV describes the debugger's PC interface. Part IV contains one chapter:

Chapter 11, "Using the Debugger PC Client/Server Interface" gives an overview of the debugger's PC interface.

- Part V describes advanced debugging topics. Part V includes the following chapters:

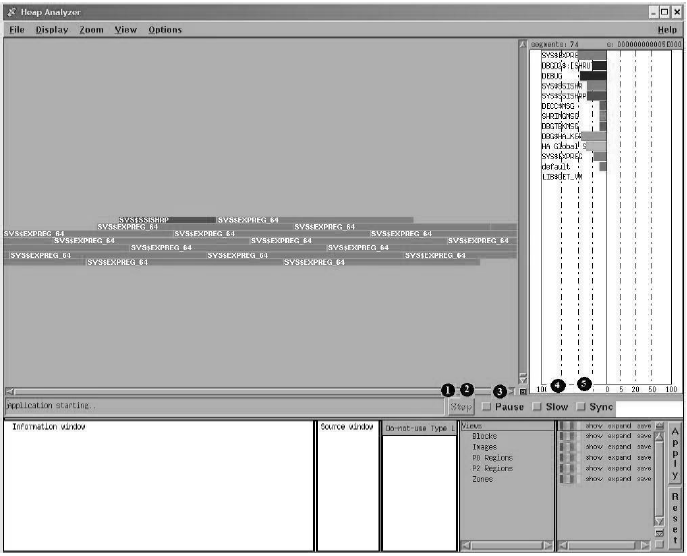

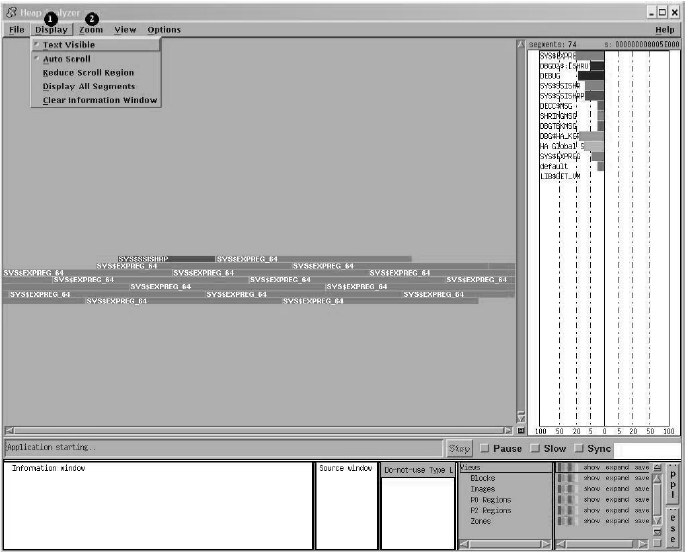

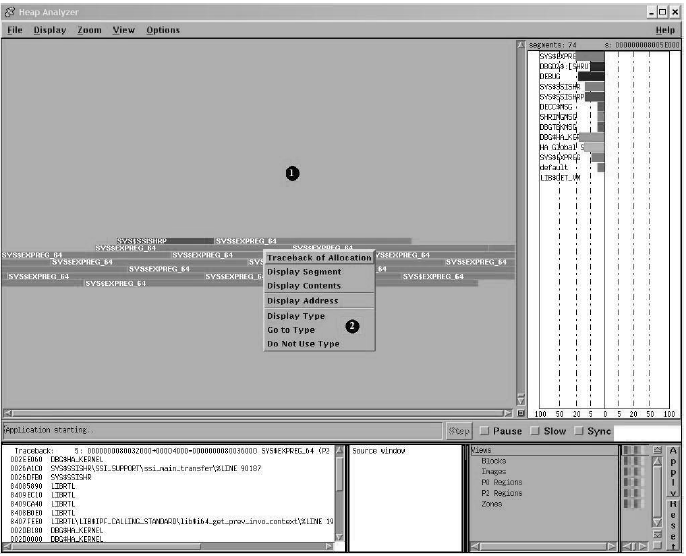

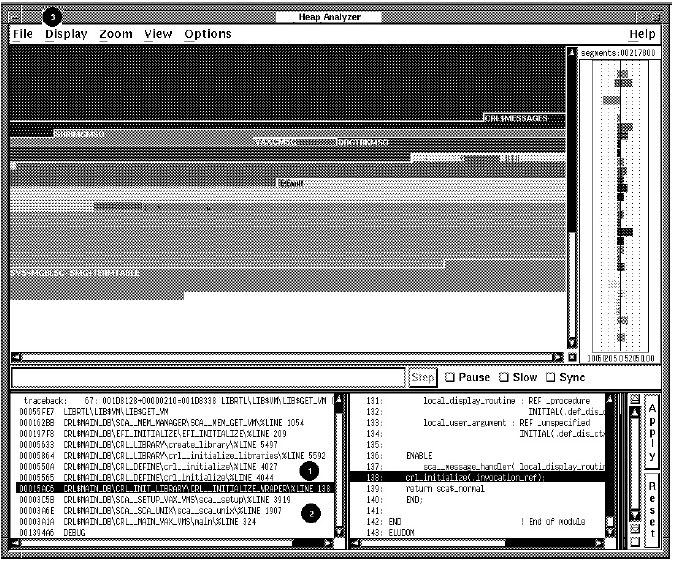

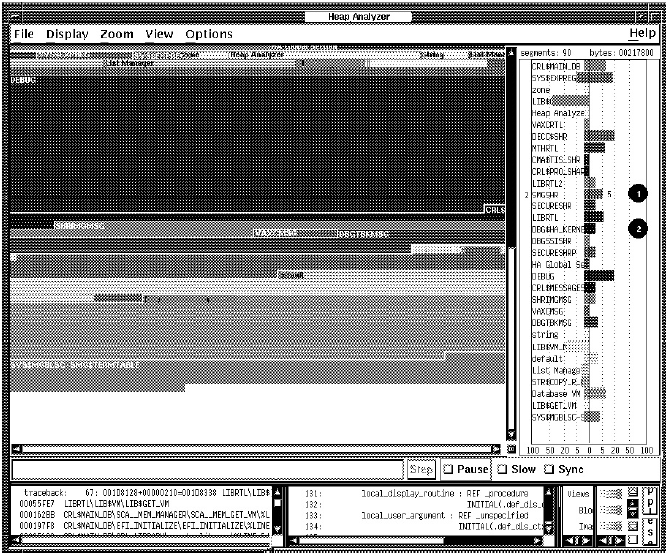

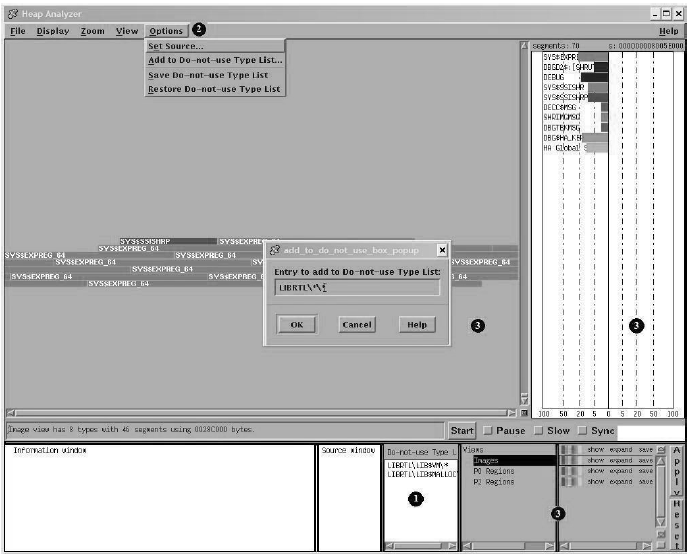

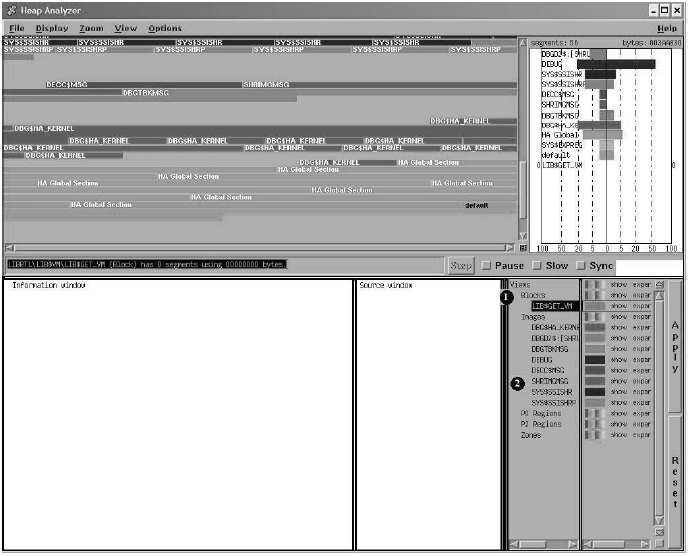

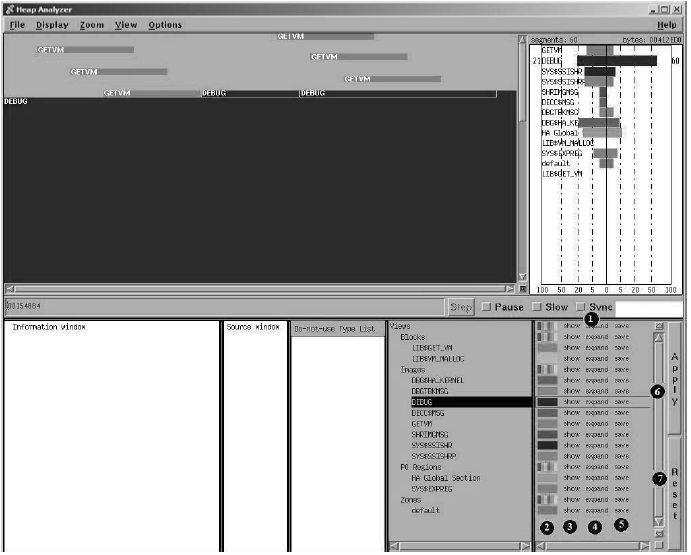

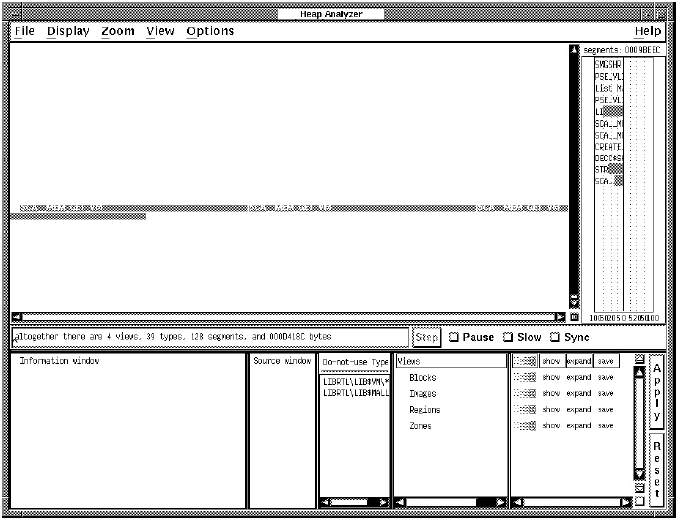

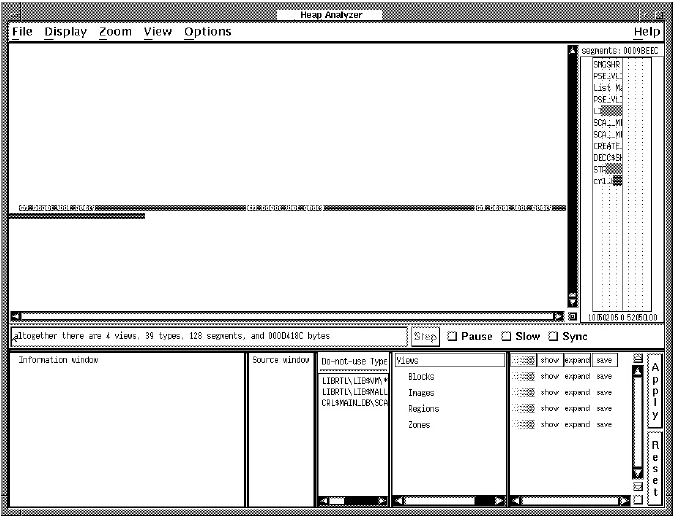

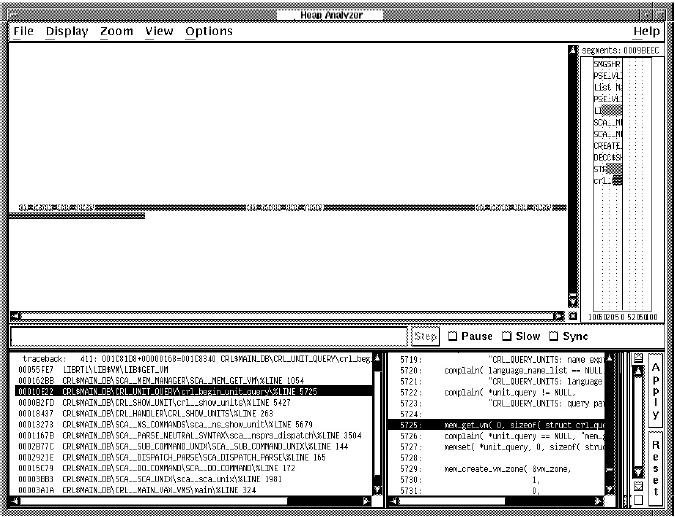

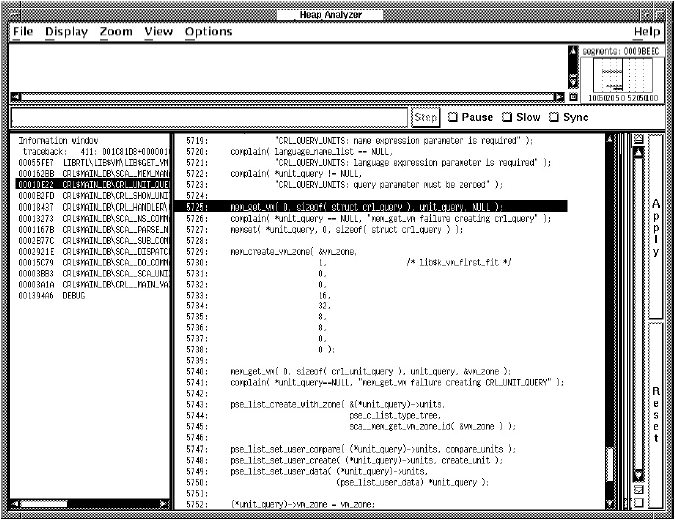

Chapter 12, "Using the Heap Analyzer ", which is organized by task, explains how to use the debugger's Heap Analyzer.

Chapter 13, "Additional Convenience Features" explains additional convenience features, such as key definitions and other customizations.

Chapter 14, "Debugging Special Cases" explains some special cases, such as debugging optimized programs and multilanguage programs.

Chapter 15, "Debugging Multiprocess Programs" explains how to debug multiprocess programs.

Chapter 16, "Debugging Tasking Programs" explains how to debug tasking (multithread) programs.

- Part VI is the debugger command dictionary, followed by the appendixes:

Appendix A, " Predefined Key Functions" lists the keypad-key definitions that are predefined by the debugger.

Appendix C, "Built-In Symbols and Logical Names" identifies all of the debugger built-in symbols and logical names.

Appendix D, "Summary of Debugger Support for Languages" identifies the debugger support for languages.

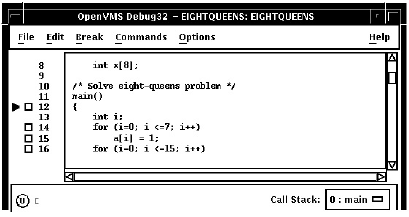

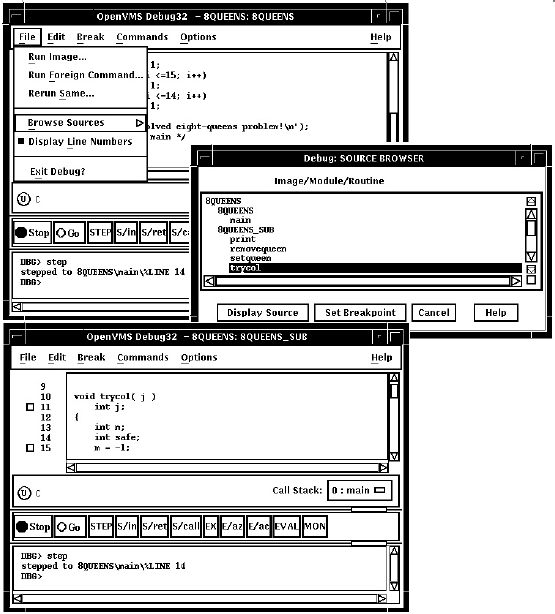

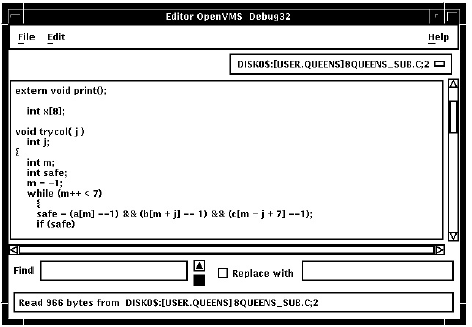

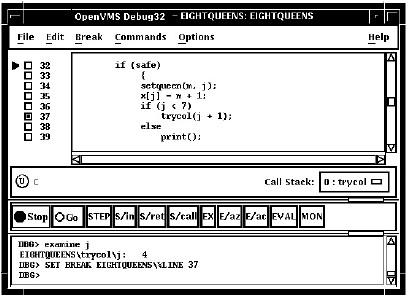

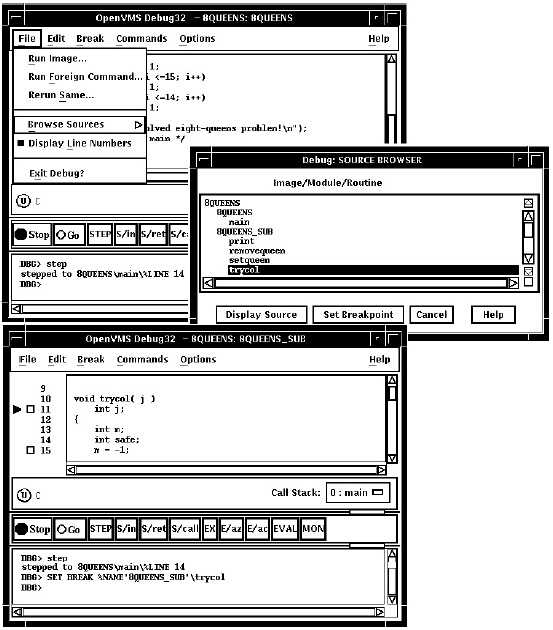

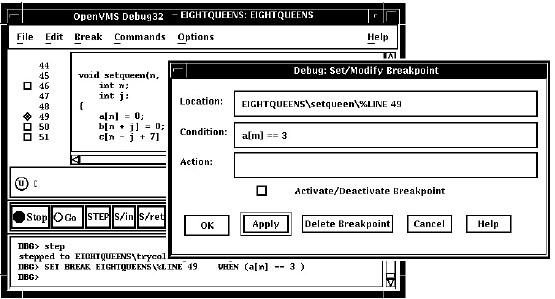

Appendix E, "EIGHTQUEENS.C" contains the source code of the programs shown in the figures in Chapter 8, "Introduction ", Chapter 9, "Starting and Ending a Debugging Session", and Chapter 10, "Using the Debugger".

4. Related Documents

The following documents may also be helpful when using the debugger.

Programming Languages

This manual emphasizes debugger usage that is common to all or most supported languages. For more information specific to a particular language, see:

The debugger's online help system (see Section 2.1, ''Entering Debugger Commands and Accessing Online Help'')

The documentation supplied with that language, particularly regarding compiling and linking the program for debugging

The VAX MACRO and Instruction Set Reference Manual or the MACRO-64 Assembler for OpenVMS AXP Systems Reference Manual for information about assembly-language instructions and the MACRO assembler

Linker Utility

For information about the linking of programs or shareable images, see the VSI OpenVMS Linker Utility Manual.

Delta/XDelta Debugger

For information about debugging code in supervisor, executive, or kernel modes (that is, in other than user mode), see the VSI OpenVMS Delta/XDelta Debugger Manual in the OpenVMS documentation set. This manual contains information about debugging programs that run in privileged processor mode or at an elevated interrupt priority level.

OpenVMS Alpha System-Code Debugger

See the VSI OpenVMS System Analysis Tools Manual for information on debugging operating system code. This manual describes how to activate the OpenVMS System-Code Debugger through the OpenVMS Debugger, and debug within the OpenVMS System-Code Debugger environment.

For information on the OpenVMS System-Code Debugger-specific commands, see the CONNECT and REBOOT commands in Part VI.

DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS

For general information about the DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS user interface, see the Using VSI DECwindows Motif for OpenVMS.

5. VSI Encourages Your Comments

You may send comments or suggestions regarding this manual or any VSI document by sending electronic mail to the following Internet address: <docinfo@vmssoftware.com>. Users who have VSI OpenVMS support contracts through VSI can contact <support@vmssoftware.com> for help with this product.

6. OpenVMS Documentation

The full VSI OpenVMS documentation set can be found on the VMS Software Documentation webpage at https://docs.vmssoftware.com.

7. Typographical Conventions

The following conventions are used in this manual:

| Convention | Meaning |

|---|---|

Ctrl/X

| A sequence such as

Ctrl/x

indicates that you must hold down the key labeled Ctrl while you

press another key or a pointing device button. |

PF1

X | A sequence such as PF1

X indicates that you

must first press and release the key labeled PF1 and then press and

release another key (x)

or a pointing device button. |

| Enter | In examples, a key name in bold indicates that you press that key. |

... | A horizontal ellipsis in examples indicates one of the following possibilities:− Additional optional arguments in a statement have been omitted.− The preceding item or items can be repeated one or more times.− Additional parameters, values, or other information can be entered. |

. . . | A vertical ellipsis indicates the omission of items from a code example or command format; the items are omitted because they are not important to the topic being discussed. |

| ( ) | In command format descriptions, parentheses indicate that you must enclose choices in parentheses if you specify more than one. In installation or upgrade examples, parentheses indicate the possible answers to a prompt, such as: |

Is this correct? (Y/N)

[Y] | |

| [ ] | In command format descriptions, brackets indicate optional choices. You can choose one or more items or no items. Do not type the brackets on the command line. However, you must include the brackets in the syntax for directory specifications and for a substring specification in an assignment statement. In installation or upgrade examples, brackets indicate the default answer to a prompt if you press Enter without entering a value, as in: |

Is this correct? (Y/N) [Y] | |

| | | In command format descriptions, vertical bars separate choices within brackets or braces. Within brackets, the choices are optional; within braces, at least one choice is required. Do not type the vertical bars on the command line. |

| { } | In command format descriptions, braces indicate required choices; you must choose at least one of the items listed. Do not type the braces on the command line. |

| bold type | Bold type represents the name of an argument, an attribute, or a reason. In command and script examples, bold indicates user input. Bold type also represents the introduction of a new term. |

| italic type | Italic type indicates important information, complete titles of manuals, or variables. Variables include information that varies in system output (Internal error number), in command lines (/PRODUCER=name), and in command parameters in text (where dd represents the predefined code for the device type). |

| UPPERCASE TYPE | Uppercase type indicates a command, the name of a routine, the name of a file, or the abbreviation for a system privilege. |

Example |

This typeface indicates code examples, command examples, and interactive screen displays. In text, this type also identifies website addresses, UNIX command and pathnames, PC-based commands and folders, and certain elements of the C programming language. |

| – | A hyphen at the end of a command format description, command line, or code line indicates that the command or statement continues on the following line. |

| numbers | All numbers in text are assumed to be decimal unless otherwise noted. Nondecimal radixes—binary, octal, or hexadecimal—are explicitly indicated. |

Part I. Introduction to the Debugger

Chapter 1. Introduction to the Debugger

An overview of debugger features

Instructions to compile and link your program for debugging

Instructions to start and end a debugging session

A list of the debugger commands grouped by function

For a tutorial introduction to basic debugging tasks, see Chapter 2, "Getting Started with the Debugger ".

1.1. Overview of the Debugger

The OpenVMS Debugger is a tool to locate run-time programming or logic errors, also known as bugs, in a program that has been compiled and linked successfully but does not run correctly. For example, the program might give incorrect output, go into an infinite loop,or terminate prematurely.

Control and observe execution of the program

Display and browse through the source code of the program to identify instructions and variables worth scrutiny

Suspend program execution at specified points in order to monitor changes in variables and other program entities

Change the value of a variable and, in some cases, test the modification without having to edit the source code, recompile, and relink

Trace the execution path of the program

Monitor exception conditions and language-specific events

These are basic debugging techniques. After locating program errors,you can edit the source code and compile, link, execute, and test the corrected version.

As you use the debugger and its documentation, you will discover and develop variations on the basic techniques. You can also customize the debugger for your own needs. Section 1.1.1, ''Functional Features''summarizes the features of the OpenVMS Debugger.

1.1.1. Functional Features

Programming Language Support

Ada | BASIC | BLISS | C |

C++ | COBOL | Fortran | MACRO-32 Note that MACRO-32 must be compiled with the AMACRO compiler. |

MACRO-64 | Pascal | PL/I |

|

Assembler (IAS ) | BASIC | BLISS | C |

C++ | COBOL | Fortran | MACRO-32. Note that MACRO-32 must be compiled with the AMACRO compiler. |

IMACRO | PASCAL |

The debugger recognizes the syntax, data types, operators, expressions,scoping rules, and other constructs of a supported language. You can change the debugging context from one language to another (with the SET LANGUAGE command) during a debugging session.

Symbolic Debugging

The debugger is a symbolic debugger. You can refer to program locations by the symbols used in your program — the names of variables, routines, labels, and so on. You can also specify explicit memory addresses or machine registers if you choose.

Support for All Data Types

The debugger recognizes the data types generated by the compilers of all supported languages, such as integer, floating-point, enumeration, record,array, and so on, and displays the values of each program variable according to its declared type.

Flexible Data Format

With the debugger, you can enter and display a variety of data forms and data types. The source language of the program determines the default format for the entry and display of data. However, you can select other formats as needed.

Starting or Resuming Program Execution

Once the program is under control of the debugger, you can start or resume program execution with the GO or STEP command. The GO command causes the program to execute until specified events occur (the PC points to a designated line of code, a variable is modified, an exception is signaled, or the program terminates). You can use the STEP command to execute a specified number instructions or lines of source code, or until the program reaches the next instruction of a specified class.

Breakpoints

You can set a breakpoint with the SET BREAK command, to suspend program execution at a specified location in order to check the current status of the program. You can also direct the debugger to suspend execution when the program is about to execute an instruction of a specific class. You can also suspend execution when certain events occur, such as exceptions and tasking (multithread) events.

Tracepoints

You can set a tracepoint with the SET TRACE command, to cause the debugger to report each time that program execution reaches a specified location (that is, each time the program counter (PC) references that location). As with the SET BREAK command, you can also trace the occurrence of classes of instructions and monitor the occurrence of certain events, such as exceptions and tasking (multithread) events.

Watchpoints

You can set a watchpoint with the SET WATCH command to cause the debugger to suspend program execution whenever a particular variable (or other specified memory location) has been modified, at which point the debugger reports the old and new values of the variable.

Manipulation of Variables and Program Locations

You can use the EXAMINE command to determine the value of a variable or memory location. You can use the DEPOSIT command to change that value. You can then continue execution of the program to determine the effect of the change without having to recompile, relink, and rerun the program.

Evaluation of Expressions

You can use the EVALUATE command to compute the value of a source-language expression or an address expression in the syntax of the language to which the debugger is currently set.

Control Structures

You can use logical control structures (FOR, IF, REPEAT, WHILE) in commands to control the execution of other commands.

Shareable Image Debugging

You can debug shareable images (images that are not directly executable). The SET IMAGE command enables you to access the symbols declared in as shareable image (that was compiled and linked with the /DEBUG qualifiers).

Multiprocess Debugging

You can debug multiprocess programs (programs that run in more than one process). The SHOW PROCESS and SET PROCESS commands enable you to display process information and to control the execution of images in individual processes.

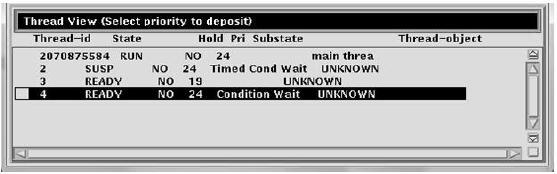

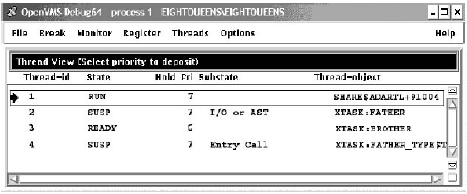

Task Debugging

You can debug tasking programs (also known as multithread programs). These programs use POSIX Threads Library or POSIX 1003.1b services, or use language-specific tasking services (for example, Ada tasking programs). The SHOW TASK and SET TASK commands enable you to display task information and to control the execution of individual tasks.

Terminal and Workstation Support

The debugger supports all VT-series terminals and VAX workstations.

1.1.2. Convenience Features

Online Help

Online help is always available during a debugging session. Online help contains information about all debugger commands and additional selected topics.

Source Code Display

During a debugging session, you can display the source code for program modules written in any of the languages supported by the OpenVMS Debugger.

Screen Mode

In screen mode, you can capture and display various kinds of information in scrollable display units. You can move these display units around the screen and resize them as needed. Automatically updated source, instruction, and register displays units are available. You can selectively direct debugger input, output, and diagnostic messages to specific display units. You can also create display units to capture the output of specific command sequences.

Kept Debugger

The kept debugger enables you to run different program images or rerun the same image from the current debugging session without having to first exit and restart the debugger. When you rerun a program, you can choose to retain or cancel any previously set breakpoints, as well as most trace points and watch points.

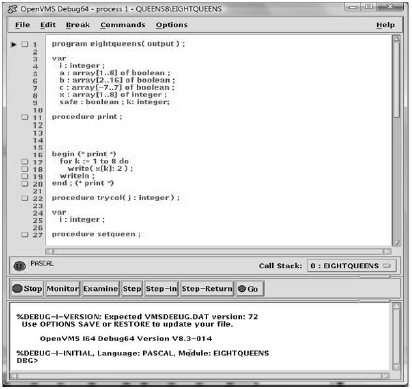

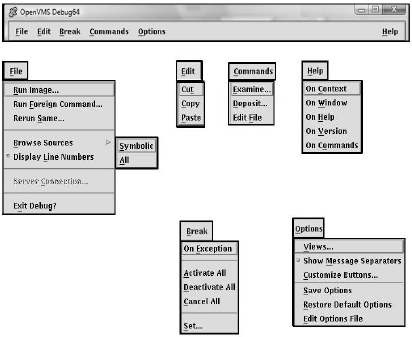

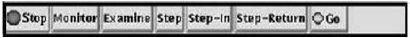

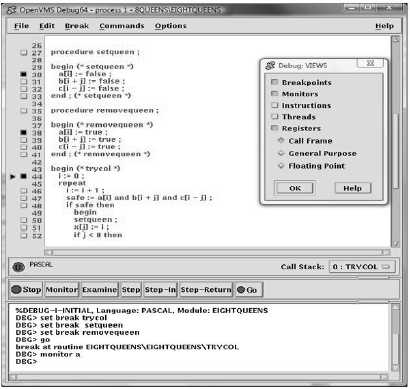

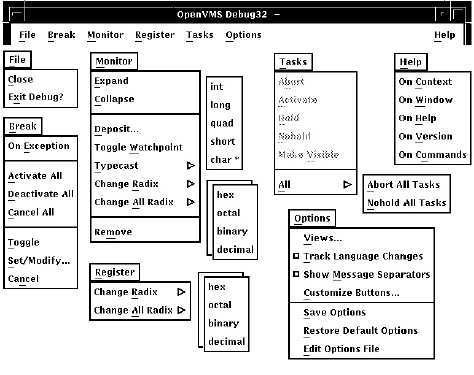

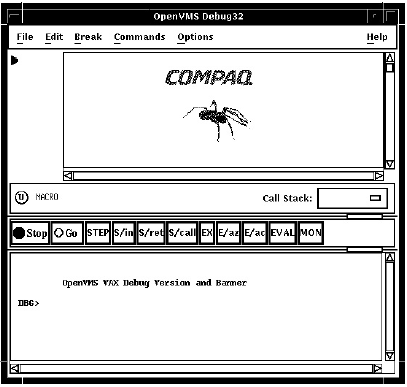

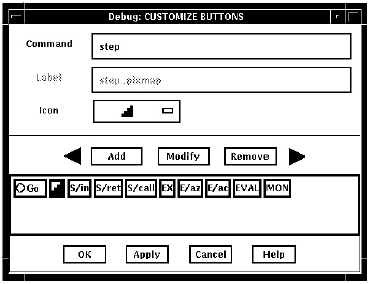

DECwindows Motif User Interface

The OpenVMS Debugger has an optional HP DECwindows Motif graphical user interface (GUI) that provides access to common debugger commands by means of push buttons, pull down menus, and pop up menus. The GUI is an optional enhancement to the debugger command line interface that is available on workstations running DECwindows Motif. When using the GUI, you have full command-line access to all debugger commands that are relevant within a DECwindows Motif environment.

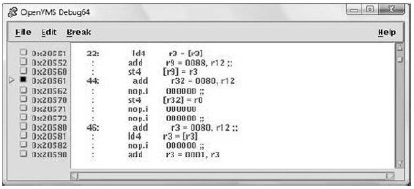

Microsoft Windows Interface

The OpenVMS Debugger has an optional client/server configuration that allows you to access the debugger and its functions from a PC running on your supplied Microsoft operating system. This debugger implementation has a debug server that runs on OpenVMS on an Alpha or Integrity server CPU, and a debug client interface that runs on Microsoft operating systems on an Intel or Alpha CPU.

Client/Server Configuration

The client/server configuration allows you to debug programs that run on an OpenVMS node remotely from another OpenVMS node using the DECwindows Motif user interface, or from a PC using the Microsoft Windows interface. Up to 31 debug clients can simultaneously access the same debug server,which allows many debugging options.

Keypad Mode

When you start the debugger, several predefined debugger command sequences are assigned to the keys of the numeric keypad of the VT52, VT100, and LK201 keyboards. You can also create your own key definitions.

Source Editing

As you find errors during a debugging session, you can use the EDIT command to use any editor available on your system. You can specify the editor with the SET EDITOR command. If you use the Language-Sensitive Editor (LSE), the editing cursor is automatically positioned within the source file corresponding to the source code that appears in the screen-mode source display.

Command Procedures

You can direct the debugger to execute a command procedure (a file of debugger commands) to re-create a debugging session, to continue a previous session, or to avoid typing the same debugger commands many times during a debugging session. In addition, you can pass parameters to command procedures.

Initialization Files

You can create an initialization file that contains debugger commands to set default debugging modes, screen display definitions, keypad key definitions, symbol definitions, and so on. Upon start up, the OpenVMS Debugger automatically executes the initialization file to create the predefined debugging environment.

Log Files

You can create a log file to contain a record of command input and debugger output. You can then use the log file to analyze the debugging session, or edit the file for use as a command procedure in subsequent debugging sessions.

Symbol Definitions

You can define your own symbols to represent lengthy commands, address expressions, or values in abbreviated form.

1.2. Preparing an Executable Image for Debugging

To take full advantage of symbolic debugging, you must first compile and link the program's modules (compilation units) using the compiler and linker /DEBUG qualifiers as explained in Section 1.2.1, ''Compiling a Program for Debugging'' and Section 1.2.2, ''Linking a Program for Debugging''.

1.2.1. Compiling a Program for Debugging

FORMS.EXE, that consists of two source modules:

FORMS.C and INVENTORY.C.

FORMS.C is the main program module. $ CC/DEBUG/NOOPTIMIZE INVENTORY,FORMS

Note that the /DEBUG and /NOOPTIMIZE qualifiers are compiler command defaults for some languages. These qualifiers are used in the example for emphasis. (For information about compiling programs in a specific language, see the documentation for that language.)

The /DEBUG qualifier in the compiler command in Example 1.1, ''Compiling a Program with the /DEBUG Qualifier'' directs the compiler to include the symbol

information associated with FORMS.C and

INVENTORY.C in object modules

FORMS.OBJ and INVENTORY.OBJ,

respectively. This enables you to refer to the symbolic names of variables,

routines,and other declared symbols while debugging the program. Only object files

created with the /DEBUG qualifier contain symbol information. You

can control whether to include all symbol information or only that required to trace

program flow (see Section 5.1.1, ''Compiling'').

Some compilers optimize the object code to reduce the size of the program or to make it run faster. In such cases the object code does not always match the source code, which can make debugging more difficult. To avoid this, compile the program with the /NOOPTIMIZE command qualifier (or equivalent). After the non-optimized program has been debugged, you can recompile and test it again without the /NOOPTIMIZE qualifier to take advantage of optimization. Section 14.1, ''Debugging Optimized Code'' describes some of the effects of optimization.

1.2.2. Linking a Program for Debugging

FORMS.EXE that consists of two source modules:

FORMS.C and INVENTORY.C.

FORMS.C is the main program module. Both source modules

were compiled with the /DEBUG qualifier (see Example 1.1, ''Compiling a Program with the /DEBUG Qualifier'').

$ LINK/DEBUG FORMS,INVENTORY

In Example 1.2, the /DEBUG qualifier in the LINK command directs the linker to include in the executable image all symbol information that is contained in the object modules being linked. Most languages require that you specify all included object modules in the LINK command. See Section 5.1.3, ''Linking'' for more details on how to control symbol information with the LINK command.

The name of the

.DSFfile must match the name of the.EXEfile being debugged.You must define DBG$IMAGE_DSF_PATH to point to the directory that contains the

.DSFfile.

$ CC/DEBUG/NOOPTIMIZE TESTPROGRAM

$ LINK/DSF=TESTDISK:[TESTDIR]TESTPROGRAM.DSF TESTPROGRAM

$ DEFINE DBG$IMAGE_DSF_PATH TESTDISK:[TESTDIR]

$ DEBUG/KEEP TESTPROGRAMSee Section 5.1.5, ''Creating Separate Symbol Files (Alpha Only)'' for more information about debugging programs that have separate symbol files. See the VSI OpenVMS Linker Utility Manual for more information about using the /DSF qualifier.

1.2.3. Controlling Debugger Activation with the LINK and RUN Commands

In addition to passing symbol information to the executable image, the LINK /DEBUG command causes the image activator to start the debugger if you execute the resulting image with the DCL command RUN. (See Section 1.6, ''Starting the Debugger by Running a Program''.)

$ RUN/NODEBUG FORMS

This is convenient for checking your program once you think it is error free. Note that the data required by the debugger occupies space within the executable image. When your program is correct, you can link your program again without the /DEBUG qualifier. This creates an image with only trace back data in the debug symbol table, which creates a smaller executable file.

| LINK Command Qualifier | To Run Program without Debugger | To Run Program with Debugger |

Maximum Symbol Information Available? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

/DEBUG? |

RUN /NODEBUG |

RUN |

Full |

|

None or /TRACEBACK or /NODEBUG? |

RUN |

RUN /DEBUG |

Only traceback? |

|

/NOTRACEBACK |

RUN |

RUN /DEBUG? |

None |

|

/DSF? |

RUN |

DEBUG /KEEP? |

Full |

|

/DSF? |

RUN |

DEBUG /SERVER? |

Full |

1.3. Debugging a Program with the Kept Debugger

Start the kept debugger and then bring a program under debugger control

Rerun the same program from the current debugging session

Run another program from the current debugging session

Interrupt program execution and abort debugger commands

Interrupt a debugging session and then return to the debugging session

1.3.1. Starting the Kept Debugger

This section explains how to start the kept debugger from DCL level ($) and bring your program under debugger control. Section 1.6, ''Starting the Debugger by Running a Program'' and Section 1.7, ''Starting the Debugger After Interrupting a Running Program'' describe other ways to invoke the debugger.

Note

- If a previous debugger process has not completely stopped, you may see the following error at debugger startup:

%DEBUG-E-INTERR, internal debugger error in DBGMRPC\DBG$WAIT_FOR_EVENT got an ACKTo fix this problem, exit the debugger. Then use the DCL command SHOW PROCESS /SUBPROCESS to check whether any debugger subprocesses exist. If so, stop them by using the DCL command STOP and then restart the debugger.

Running a sequence of many large programs can cause the debugger to fail because it has run out of memory, global sections, or some other resource.

To fix this problem, exit the debugger and restart the debugging session.

Verify that you have compiled and linked the program as explained in Section 1.2, ''Preparing an Executable Image for Debugging''.

- Enter the following command line:

$ DEBUG/KEEP

Upon startup, the debugger displays its banner, executes any user-defined initialization file (see Section 13.2, ''Using a Debugger Initialization File''), and displays its

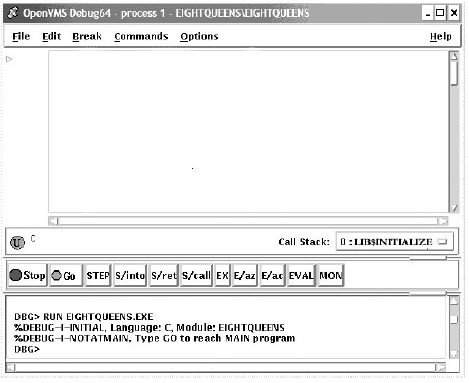

DBG>prompt to indicate that you can now enter debugger commands, as explained in Section 2.1, ''Entering Debugger Commands and Accessing Online Help''. - Bring your program under debugger control with the debugger RUN command, specifying the executable image of your program as the parameter. For example:

DBG> RUN FORMS %DEBUG-I-INITIAL,Language: C, Module: FORMS DBG>

The message displayed indicates that this debugging session is initialized fora C program and that the name of the main program unit (the module containing the image transfer address) is FORMS. The initialization sets up language-dependent debugger parameters. These parameters control the way the debugger parses names and expressions, formats debugger output, and so on. See Section 4.1.9, ''Language Dependencies and the Current Language'' for more information about language-dependent parameters.

%DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Type GO to reach main program

With some of these programs (for example, Ada programs), the temporary breakpoint enables you to debug the initialization code using full symbolic information. See Section 14.3, ''Debugging Multilanguage Programs'' for more information.

At this point, you can debug your program as explained in Chapter 2, "Getting Started with the Debugger ".

RUN and RERUN Command Options for Programs That Require Arguments

Some programs require arguments. This section explains how to use the RUN and RERUN commands with the /ARGUMENTS and /COMMAND qualifiers when debugging a program with the kept debugger.

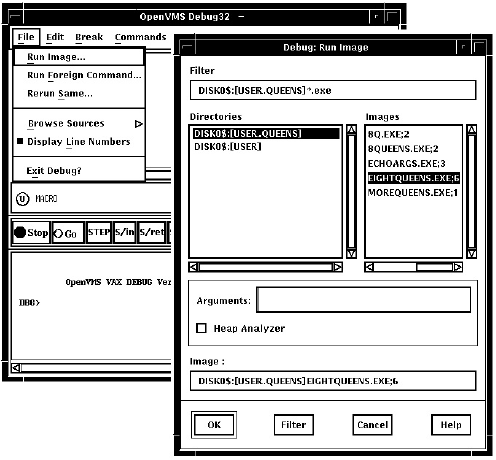

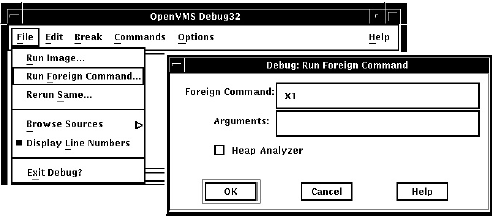

After starting the kept debugger, you can specify the image to be debugged by entering the RUN command with an image name, or the RUN /COMMAND command with a DCL foreign command. Note that you can specify a DCL foreign command only with the /COMMAND qualifier to the RUN command.

You can specify a list of arguments with the /ARGUMENTS qualifier to the RUN and RERUN commands.

echoargs.c,a program that echoes

the input arguments to the terminal:

#include <stdio.h>

main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i;

for (i = 0; i < argc; i++)

printf("%s\n", argv[i]);

}$ cc/debug/noopt echoargs.c $ link/debug echoargs

RUN with /COMMAND and /ARGUMENTS

RERUN with /ARGUMENTS

RUN with /ARGUMENTS and image name

RUN with /COMMAND and /ARGUMENTS

echo.The /ARGUMENTS qualifier specifies arguments fa

sol la mi. The first GO command executes the initialization code of

echoargs.exe after which the debugger suspends program

execution at the temporary breakpoint at the start of the program. The second GO

command executes echoargs.exe, which correctly echoes the

arguments to the

screen.$ DEBUG/KEEP

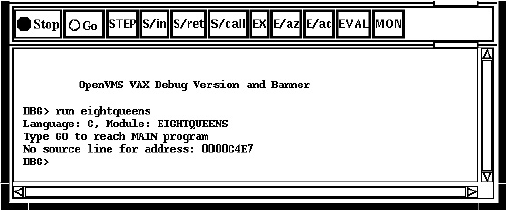

Debugger Banner and Version Number

DBG> RUN/COMMAND="echo"/ARGUMENTS="fa sol la mi"

%DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Language: C, Module: ECHOARGS

%DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Type GO to reach main program

DBG> GO

break at routine ECHOARGS\main

1602: for (i = 0; i < argc; i++)

DBG> GO

_dsa1:[jones.test]echoargs.exe;2

fa

sol

la

mi

%DEBUG-I-EXITSTATUS,is '%SYSTEM-S-NORMAL, Normal successful completion'This section of the debugger session shows the use of the RERUN command with the

/ARGUMENTS qualifier to run the same image again, with new arguments fee

fii foo fum. (If you omit the /ARGUMENTS qualifier, the

debugger reruns the program with the arguments used previously.)

echoargs.exe after which the debugger suspends program

execution at the temporary breakpoint at the start of the program. The second GO

command executes echoargs.exe, which correctly echoes the

arguments to the

screen.DBG> RERUN/ARGUMENTS="fee fii foo fum" %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Language: C, Module: ECHOARGS %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Type GO to reach main program DBG> GO break at routine ECHOARGS\main 1602: for (i = 0; i < argc; i++) DBG> GO _dsa1:[jones.test]echoargs.exe;2 fee fii foo fum %DEBUG-I-EXITSTATUS,is '%SYSTEM-S-NORMAL, Normal successful completion'

This section of the debugging session uses the RUN command to invoke a fresh image

of echoargs, with the /ARGUMENTS qualifier to specify a new set

of arguments a b c.

echoargs.exe after which the debugger suspends program

execution at the temporary breakpoint at the start of the program. The second GO

command executes echoargs.exe,which correctly echoes the

arguments to the

screen.DBG> RUN/ARGUMENTS="a b c" echoargs %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Language: C, Module: ECHOARGS %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN,Type GO to reach main program DBG> GO break at routine ECHOARGS\main 1602: for (i = 0; i < argc; i++) DBG> GO _dsa1:[jones.test]echoargs.exe;2 a b c %DEBUG-I-EXITSTATUS,is '%SYSTEM-S-NORMAL, Normal successful completion' DBG> quit

RUN Command Restrictions

You can use the RUN command only if you started the debugger with the DCL command DEBUG /KEEP.

You cannot use the RUN command to connect the debugger to a running program (see Section 1.7, ''Starting the Debugger After Interrupting a Running Program'').

Unless you are using the debugger client/server interface, you cannot run a program under debugger control over a network link. See Section 9.9, ''Starting the Motif Debug Client'' and Chapter 11, "Using the Debugger PC Client/Server Interface" for more information about using the debugger client/server interface.

1.3.2. When Your Program Completes Execution

%DEBUG-I-EXITSTATUS,is '%SYSTEM-S-NORMAL, Normal successful completion')

You can rerun your program from the same debugging session (see Section 1.3.3, ''Rerunning the Same Program from the Kept Debugger'').

You can run another program from the same debugging session (see Section 1.3.4, ''Running Another Program from the Kept Debugger'').

You can end the debugging session (see Section 1.8, ''Ending a Debugging Session'').

1.3.3. Rerunning the Same Program from the Kept Debugger

DBG> RERUN %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Language: C, Module: ECHOARGS %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Type GO to reach main program DBG>

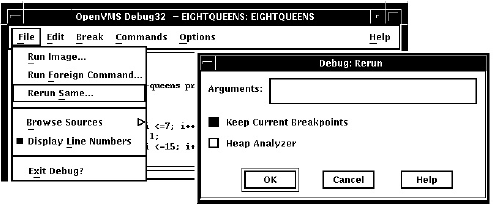

The RERUN command terminates the image you were debugging and brings a fresh copy of that image under debugger control, pausing at the start of the main source module as if you had used the RUN command (see Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger'').

When you use the RERUN command you can save the current state (activated or deactivated) of any breakpoints, trace points, and static watch points. Note that the state of a particular nonstatic watchpoint might not be saved, depending on the scope of the variable being watched relative to the main program unit (where execution restarts). RERUN /SAVE is the default. To clear all breakpoints tracepoints, and watchpoints, enter RERUN /NOSAVE.

The RERUN command invokes the same version of the image that is currently under debugger control. To debug a different version of that program (or a different program) from the same debugging session, use the RUN command. To rerun a program with new arguments, use the /ARGUMENTS qualifier (see the section called “RUN and RERUN Command Options for Programs That Require Arguments”).

1.3.4. Running Another Program from the Kept Debugger

DBG> RUN TOTALS %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Language: FORTRAN, Module: TOTALS DBG>

The debugger loads the program and pauses execution at the start of the main source module.

For more information about startup conditions and restrictions, see Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger''.

For information about all RUN command options, see the debugger RUN command description.

1.4. Interrupting Program Execution and Aborting Debugger Commands

DBG> GO . . . Ctrl/C DBG>

You can also press Ctrl/C to abort the execution of a debugger command. This is useful if, for example, the debugger is displaying along stream of data.

Pressing Ctrl/C when the program is not running or when the debugger is not performing an operation has no effect.

If your program has a Ctrl/C AST (asynchronous system trap) service routine enabled, use the SET ABORT_KEY command to assign the debugger's abort function to another Ctrl/key sequence. To identify the abort key that is currently defined, enter the SHOW ABORT_KEY command.

Pressing Ctrl/Y from within a debugging session has the same effect as pressing Ctrl/Y during the execution of a program. Control is returned to the DCL command interpreter ($ prompt).

1.5. Pausing and Resuming a Debugging Session

Use the debugger SPAWN command to create a subprocess.

Use the debugger ATTACH command to attach to an existing process or subprocess.

DBG> SPAWN DIR [JONES.PROJECT2]*.FOR . . . Control returned to process JONES_1 DBG>

DBG> SPAWN MAIL MAIL> READ/NEW . . . MAIL> EXIT Control returned to process JONES_1 DBG>

DBG> SPAWN $ RUN PROG2 . . . $ ATTACH JONES_1 Control returned to process JONES_1 DBG>

If you plan to go back and forth several times between your debugging session and a spawned subprocess (which might be another debugging session), use the debugger ATTACH command to attach to that subprocess. Use the DCL command ATTACH to return to the parent process. Because you do not create a new subprocess every time you leave the debugger, you use system resources more efficiently.

If you are running two debugging sessions simultaneously, you can define anew debugger prompt for one of the sessions with the SET PROMPT command. This helps you differentiate the sessions.

1.6. Starting the Debugger by Running a Program

You can bring your program under control of the non-kept debugger in one step by entering the

DCL command RUN filespec.

Note that when running the non-kept debugger, you cannot use the debugger RERUN or RUN features explained in Section 1.3.3, ''Rerunning the Same Program from the Kept Debugger'' and Section 1.3.4, ''Running Another Program from the Kept Debugger'', respectively. To rerun the same program or run another program under debugger control, you must first exit the debugger and start it again.

$ RUN FORMS

Debugger Banner and Version Number

%DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Language: C, Module: FORMS

DBG>Upon startup, the debugger displays its banner, executes any user-defined initialization file, sets the language-dependent parameters to the source language of the main program, suspends execution at the start of the main program,and prompts for commands.

For more information about startup conditions, see Section 1.2.3, ''Controlling Debugger Activation with the LINK and RUN Commands'' and Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger''.

1.7. Starting the Debugger After Interrupting a Running Program

You can bring a program that is executing freely under debugger control. This is useful either if you suspect that the program might be in an infinite loop or if you see erroneous output.

Verify that you have compiled and linked the program as explained in Section 1.2, ''Preparing an Executable Image for Debugging''.

Enter the DCL command RUN/NODEBUG

filespecto execute the program without invoking the debugger.Press Ctrl/Y to interrupt the executing program. Control passes to the DCL command interpreter.

Enter the DCL command DEBUG. This invokes the non-kept debugger.

$ RUN/NODEBUG FORMS . . . Ctrl/Y Interrupt $ DEBUG Debugger Banner and Version Number %DEBUG-I-NOTATMAIN, Language: C, Module: FORMS DBG>

Upon startup, the debugger displays its banner, executes any user-defined initialization file, sets the language-dependent parameters to the source language of the module where execution is interrupted, and prompts for commands.

To know where the execution is interrupted, enter the SHOW CALLS command to determine where execution is paused and to display the sequence of routine calls on the call stack (the SHOW CALLS command is described in Section 2.3.3, ''Determining Where Execution Is Paused'').

Note that when running the non-kept debugger, you cannot use the debugger RERUN or RUN features explained in Section 1.3.3, ''Rerunning the Same Program from the Kept Debugger'' and Section 1.3.4, ''Running Another Program from the Kept Debugger'', respectively. To rerun the same program or run another program under debugger control, you must first exit the debugger and start it again.

For more information about startup conditions, see Section 1.2.3, ''Controlling Debugger Activation with the LINK and RUN Commands'' and Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger''.

1.8. Ending a Debugging Session

DBG> EXIT $

The QUIT command starts the debugger exit handlers to close log files, restores the screen and keypad states, and so on.

The EXIT command and Ctrl/Z function identically. They perform the same functions as the QUIT command,and additionally execute any exit handlers that are declared in your program.

1.9. Debugging a Program on a Workstation Running DECwindows Motif

If you are at a workstation running HP DECwindows Motif, by default the debugger starts up in the HP DECwindows Motif user interface, which is displayed on the workstation specified by the HP DECwindows Motif application wide logical name DECW$DISPLAY.

The logical name DBG$DECW$DISPLAY enables you to override the default to display the debugger's command interface in a DECterm window, along with any program input/output (I/O).

- Enter the following definition in the DECterm window from which you plan to start the debugger:

$ DEFINE/JOB DBG$DECW$DISPLAY " "You can specify one or more space characters between the quotation marks. You should use a job definition for the logical name. If you use a process definition, it must not have the CONFINE attribute.

Start the debugger in the usual way from that DECterm window (see Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger'').The debugger's command interface is displayed in the same window.

$ DEFINE/JOB DBG$DECW$DISPLAY " "

$ DEBUG/KEEP

Debugger Banner and Version Number

DBG>You can now bring your program under debugger control as explained in Section 1.3.1, ''Starting the Kept Debugger''.For more information about the logical names DBG$DECW$DISPLAY and DECW$DISPLAY, see Section 9.8.3, ''Overriding the Debugger's Default Interface''.

On a workstation running HP DECwindows Motif, you can also run the client/server configuration of the OpenVMS debugger. See Section 9.9, ''Starting the Motif Debug Client'' for details.

1.10. Debugging a Program from a PC Running the Debug Client

Microsoft Windows (Intel)

Microsoft Windows NT Version 3.51 or greater (Intel or Alpha)

Note

The client/server interface for OpenVMS Integrity server systems is planned for a future release.

Remote access to OpenVMS Debug servers from other OpenVMS systems or from PCs running Windows 95 or Windows NT Version 3.51 or later

Client access to multiple servers, each running on the same or different OpenVMS nodes

Multiple clients on different nodes to simultaneously connect to the same server for teaching or team debugging

Debugging of multitier client/server applications that are distributed among several mixed-platform systems

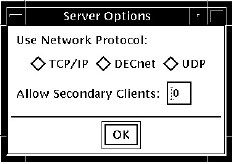

TCP/IP

UDP

DECnet

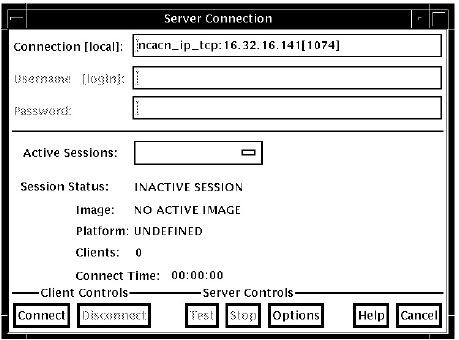

$ DEBUG/SERVER

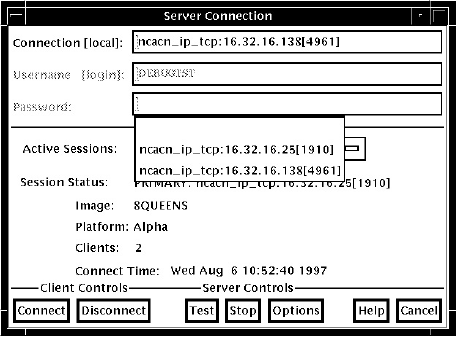

The server displays its network binding strings. You must specify one of these strings when you connect a HP DECwindows Motif or Microsoft Windows client to this server. For example:

$ DEBUG/SERVER %DEBUG-I-SPEAK: TCP/IP: YES, DECnet: YES, UDP: YES %DEBUG-I-WATCH: Network Binding: ncacn_ip_tcp:16.32.16.138[1034] %DEBUG-I-WATCH: Network Binding: ncacn_dnet_nsp:19.10[RPC224002690001] %DEBUG-I-WATCH: Network Binding: ncadg_ip_udp:16.32.16.138[1045] %DEBUG-I-AWAIT: Ready for client connection...

Note

Messages and program output appear by default in the window in which you start the server. You can redirect program output to another window as required.

For more information about using the debug client interface, see Chapter 11, "Using the Debugger PC Client/Server Interface".

1.11. Debugging Detached Processes That Run with No CLI

The design and implementation of the debugger's HP DECwindows Motif user interface requires that the process being debugged have a command line interpreter (CLI). To debug a detached process (such as a print symbiont) that does not have a CLI, you must use the character-cell (screen mode) interface to the debugger.

To do so, direct DBG$INPUT, DBG$OUTPUT and DBG$ERROR to a terminal port that is not logged in. This allows the image to be debugged with the standard character-cell interface on that terminal.

$ DEFINE/TABLE=GROUP DBG$INPUT TTA3: $ DEFINE/TABLE=GROUP DBG$OUTPUT TTA3: $ DEFINE/TABLE=GROUP DBG$ERROR TTA3: $ START/QUEUE SYS$PRINT /PROCESSOR=dev:[dir]test_program [Debugger starts up on logged-out terminal TTA3:]

1.12. Configuring Process Quotas for the Debugger

Each user needs a PRCLM quota sufficient to create an additional subprocess for the debugger, beyond the number of processes needed by the program.

You should increase each user's ENQLM quota by at least the number of processes being debugged.

You might need to increase each user's PGFLQUOTA. If a user has an insufficient PGFLQUOTA, the debugger may fail to activate or may cause "virtual memory exceeded" errors during execution.

You might need to increase each user's BYTLM and FILLM quotas. The debugger requires sufficient BYTLM and FILLM quotas to open each image file being debugged, the corresponding source files, and the debugger input, output, and log files. To increase these quotas, you can run SYS$SYSTEM:AUTHORIZE.EXE to adjust parameters in

SYSUAF.DAT.

1.13. Debugger Command Summary

The following sections list all the debugger commands and any related DCL commands in functional groupings, along with brief descriptions. During a debugging session, you can get online help on all debugger commands and their qualifiers by typing HELP at the debugger prompt (see Section 2.1, ''Entering Debugger Commands and Accessing Online Help'').

1.13.1. Starting and Ending a Debugging Session

$ DEBUG/KEEP |

(DCL) Starts the kept debugger. |

$ RUN SYS$SHARE:DEBUGSHR.EXE

|

(DCL) Starts the kept debugger. |

$ DEBUG/SERVER |

(DCL) Starts the debug server. |

$ DEBUG/CLIENT |

(DCL) Starts the debug client. |

$ RUN SYS$SHARE:DEBUGUISHR.EXE

|

(DCL) Starts the debug client. |

RUN

|

Brings a program under debugger control. |

RERUN |

Reruns the program currently under debugger control. |

$ RUN

|

(DCL) If the specified image was linked using LINK /DEBUG, starts the debugger and also brings the image under debugger control. When you start the debugger in this manner, you cannot then use the debugger RUN or RERUN commands. You can use the /[NO]DEBUG qualifiers with the RUN command to control whether the debugger is started when the program is executed. |

|

Ends a debugging session, executing all exit handlers. |

QUIT |

Ends a debugging session without executing any exit handlers declared in the program. |

|

Ctrl/C |

Aborts program execution or a debugger command without interrupting the debugging session. |

(SET, SHOW) ABORT_KEY |

(Assigns, identifies) the default Ctrl/C abort function to another Ctrl/key sequence, identifies the Ctrl/key sequence currently defined for the abort function. |

|

Ctrl/Y $ DEBUG |

(DCL) Interrupts a program that is running without debugger control and starts the debugger. |

ATTACH |

Passes control of your terminal from the current process to another process. |

SPAWN |

Creates a subprocess, which enables you to execute DCL commands without ending a debugging session or losing your debugging context. |

1.13.2. Controlling and Monitoring Program Execution

GO |

Starts or resumes program execution |

STEP |

Executes the program up to the next line, instruction, or specified instruction |

(SET,SHOW) STEP |

(Establishes, displays) the default qualifiers for the STEP command |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) BREAK |

(Sets, displays, cancels) breakpoints |

(ACTIVATE,DEACTIVATE) BREAK |

(Activates, deactivates) previously set breakpoints |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) TRACE |

(Sets, displays, cancels) tracepoints |

(ACTIVATE,DEACTIVATE) TRACE |

(Activates, deactivates) previously set tracepoints |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) WATCH |

(Sets, displays, cancels) watchpoints |

(ACTIVATE,DEACTIVATE) WATCH |

(Activates, deactivates) previously set watchpoints |

SHOW CALLS |

Identifies the currently active routine calls |

SHOW STACK |

Gives additional information about the currently active routine calls |

CALL |

Calls a routine |

1.13.3. Examining and Manipulating Data

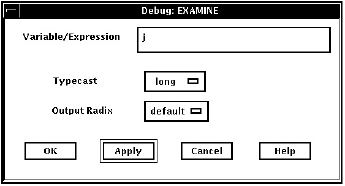

EXAMINE |

Displays the value of a variable or the contents of a program location |

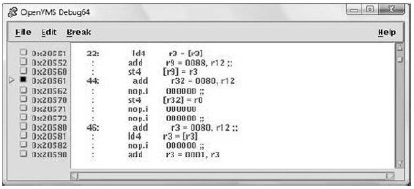

SET MODE [NO]OPERANDS |

Controls whether the address and contents of the instruction operands are displayed when you examine an instruction |

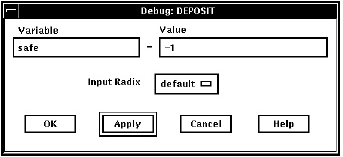

DEPOSIT |

Changes the value of a variable or the contents of a program location |

DUMP |

Displays the contents of memory in a manner similar to the DCL command DUMP |

EVALUATE |

Evaluates a language or address expression |

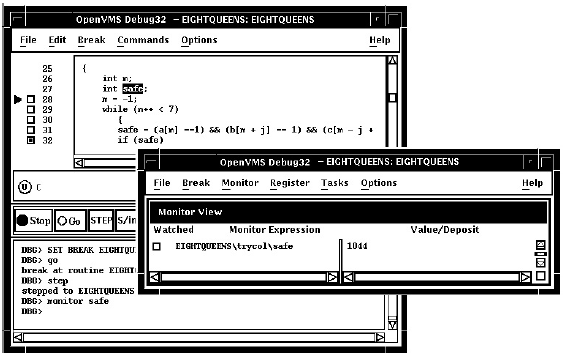

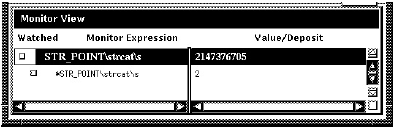

MONITOR |

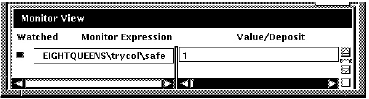

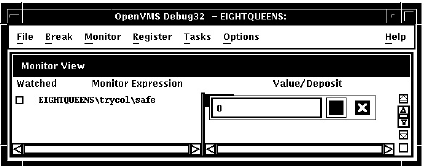

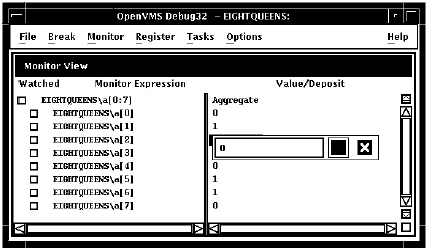

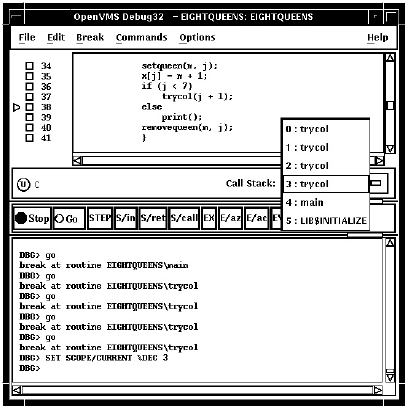

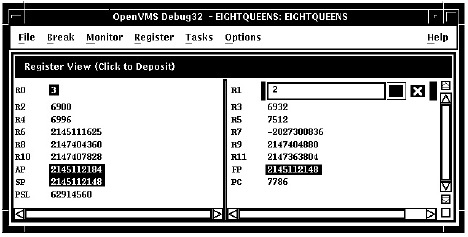

(Applies only to the debugger's HP DECwindows Motif user interface) Displays the current value of a variable or language expression in the monitor view of the HP DECwindows Motif user interface |

1.13.4. Controlling Type Selection and Radix

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) RADIX |

(Establishes, displays, restores) the radix for data entry and display |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) TYPE |

(Establishes, displays, restores) the type for program locations that are not associated with a compiler-generated type |

SET MODE [NO]G_FLOAT |

Controls whether double-precision floating-point constants are interpreted as G_FLOAT or D_FLOAT |

1.13.5. Controlling Symbol Searches and Symbolization

SHOW SYMBOL |

Displays symbols in your program |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) MODULE |

Sets a module by loading its symbol information into the debugger's symbol table, identifies, cancels a set module |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) IMAGE |

Sets a shareable image by loading data structures into the debugger's symbol table, identifies, cancels a set image |

SET MODE [NO]DYNAMIC |

Controls whether or not modules and shareable images are set automatically when the debugger interrupts execution |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) SCOPE |

(Establishes, displays, restores) the scope for symbol searches |

SYMBOLIZE |

Converts a memory address to a symbolic address expression |

SET MODE [NO]LINE |

Controls whether or not program locations are displayed

in terms of line numbers or |

SET MODE [NO]SYMBOLIC |

Controls whether or not program locations are displayed symbolically or in terms of numeric addresses |

1.13.6. Displaying Source Code

TYPE |

Displays lines of source code |

EXAMINE/SOURCE |

Displays the source code at the location specified by the address expression |

SEARCH |

Searches the source code for the specified string |

(SET,SHOW) SEARCH |

(Establishes, displays) the default qualifiers for the SEARCH command |

SET STEP [NO]SOURCE |

Enables/disables the display of source code after a STEP command has been executed or at a breakpoint, tracepoint, or watchpoint |

(SET,SHOW) MARGINS |

(Establishes, displays) the left and right margin settings for displaying source code |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) SOURCE |

(Creates, displays, cancels) a source directory search list |

1.13.7. Using Screen Mode

SET MODE [NO]SCREEN |

Enables/disables screen mode |

DISPLAY |

Creates or modifies a display |

SCROLL |

Scrolls a display |

EXPAND |

Expands or contracts a display |

MOVE |

Moves a display across the screen |

(SHOW,CANCEL) DISPLAY |

(Identifies, deletes) a display |

(SET,SHOW,CANCEL) WINDOW |

(Creates, identifies, deletes) a window definition |

SELECT |

Selects a display for a display attribute |

SHOW SELECT |

Identifies the displays selected for each of the display attributes |

SAVE |

Saves the current contents of a display into another display |

EXTRACT |

Saves a display or the current screen state into a file |

(SET,SHOW) TERMINAL |

(Establishes, displays) the terminal screen height and width that the debugger uses when it formats displays and other output |

SET MODE [NO]SCROLL |

Controls whether an output display is updated line by line or once per command |

|

Refreshes the screen |

1.13.8. Editing Source Code

EDIT |

Starts an editor during a debugging session |

(SET,SHOW) EDITOR |

(Establishes, identifies) the editor started by the EDIT command |

1.13.9. Defining Symbols

DEFINE |

Defines a symbol as an address, command, or value |

DELETE |

Deletes symbol definitions |

(SET,SHOW) DEFINE |

(Establishes, displays) the default qualifier for the DEFINE command |

SHOW SYMBOL/DEFINED |

Identifies symbols that have been defined with the DEFINE command |

1.13.10. Using Keypad Mode

SET MODE [NO]KEYPAD |

Enables/disables keypad mode |

DEFINE/KEY |

Creates key definitions |

DELETE/KEY |

Deletes key definitions |

SET KEY |

Establishes the key definition state |

SHOW KEY |

Displays key definitions |

1.13.11. Using Command Procedures, Log Files, and Initialization Files

@(execute procedure) |

Executes a command procedure |

(SET,SHOW) ATSIGN |

(Establishes, displays) the default file specification that the debugger uses to search for command procedures |

DECLARE |

Defines parameters to be passed to command procedures |

(SET,SHOW) LOG |

(Specifies, identifies) the debugger log file |

SET OUTPUT [NO]LOG |

Controls whether or not a debugging session is logged |

SET OUTPUT [NO]SCREEN_LOG |

Controls whether or not, in screen mode, the screen contents are logged as the screen is updated |

SET OUTPUT [NO]VERIFY |

Controls whether or not debugger commands are displayed as a command procedure is executed |

SHOW OUTPUT |

Identifies the current output options established by the SET OUTPUT command |

1.13.12. Using Control Structures

FOR |

Executes a list of commands while incrementing a variable |

IF |

Executes a list of commands conditionally |

REPEAT |

Executes a list of commands a specified number of times |

WHILE |

Executes a list of commands while a condition is true |

EXITLOOP |

Exits an enclosing WHILE, REPEAT, or FOR loop |

1.13.13. Debugging Multiprocess Programs

process-spec, DISPLAY

/PROCESS=).

CONNECT |

Brings a process under debugger control |

DEFINE/PROCESS_SET |

Assigns a symbolic name to a list of process specifications |

SET MODE [NO]INTERRUPT |

Controls whether execution is interrupted in other processes when it is paused in some process |

(SET,SHOW) PROCESS |

Modifies the multiprocess debugging environment, displays process information |

WAIT |

When debugging a multiprocess program, controls whether the debugger waits until all processes have stopped before prompting for another command |

1.13.14. Additional Commands

HELP |

Displays online help on debugger commands and selected topics |

ANALYZE/CRASH_DUMP |

Opens a process dump for analysis with the System Dump Debugger (SDD) |

ANALYZE/PROCESS_DUMP |

Opens a process dump for analysis with the System Code Debugger (SCD) |

(DISABLE,ENABLE,SHOW) AST |

(Disables, enables) the delivery of ASTs in the program, identifies whether delivery is enabled or disabled |

PTHREAD |

Passes a command to the POSIX Threads Debugger |

(SET,SHOW) EVENT_FACILITY |

(Establishes, identifies) the current run-time facility for Ada, POSIX Threads, and SCAN events |

(SET,SHOW) LANGUAGE |

(Establishes, identifies) the current language |

SET OUTPUT [NO]TERMINAL |

Controls whether debugger output, except for diagnostic messages, is displayed or suppressed |

SET PROMPT |

Specifies the debugger prompt |

(SET,SHOW) TASK|THREAD |

Modifies the tasking environment, displays task information |

SHOW EXIT_HANDLERS |

Identifies the exit handlers declared in the program |

SHOW MODE |

Identifies the current debugger modes established by the SET MODE command (for example, screen mode, step mode) |

SHOW OUTPUT |

Identifies the current output options established by the SET OUTPUT command |

Part II. Command Interface

Chapter 2. Getting Started with the Debugger

This chapter gives a tutorial introduction to the debugger's command interface.

Entering debugger commands and getting online help

Viewing your source code with the TYPE command and in screen mode

Controlling program execution with the GO, STEP, and SET BREAK commands, and monitoring execution with the SHOW CALLS, SET TRACE, and SET WATCH commands

Examining and manipulating data with the EXAMINE, DEPOSIT, and EVALUATE commands

Controlling symbol references with path names and the SET MODULE and SET SCOPE commands

Several examples are language specific. However, the general concepts are readily adaptable to all supported languages.

The sample debugging session in Section 2.6, ''Sample Debugging Session'' shows how to use some of this information to locate an error and correct it.

For information about starting and ending a debugging session, see Section 1.3, ''Debugging a Program with the Kept Debugger''.

2.1. Entering Debugger Commands and Accessing Online Help

DBG>) is displayed.

To enter a command, type it at the keyboard and press Return. For

example, the following command sets a watchpoint on the variable

COUNT:

DBG> SET WATCH COUNT

To list the help topics, type HELP at the prompt.

For an explanation of the help system, type HELP.

For complete rules on entering commands, type HELP

Command_Format.To display help on a particular command, type HELP

command. For example, to display HELP on the SET WATCH command, type HELP SET WATCH.To list commands grouped by function, type HELP

Command_Format.

- New_Features

- Release_Notes

- Address_Expressions

- Built_in_Symbols

- DECwindows_Interface

- Keypad_Definitions

- Language_Support

- Logical_Names

- Messages (diagnostic messages)

- Path_Names (to qualify symbolic names)

- Screen_Mode

- SS$_DEBUG condition (to start debugger from program)

- System_Management

To display help about any of these topics, type HELP

topic. For example, to display information

about diagnostic messages, type HELP Messages.

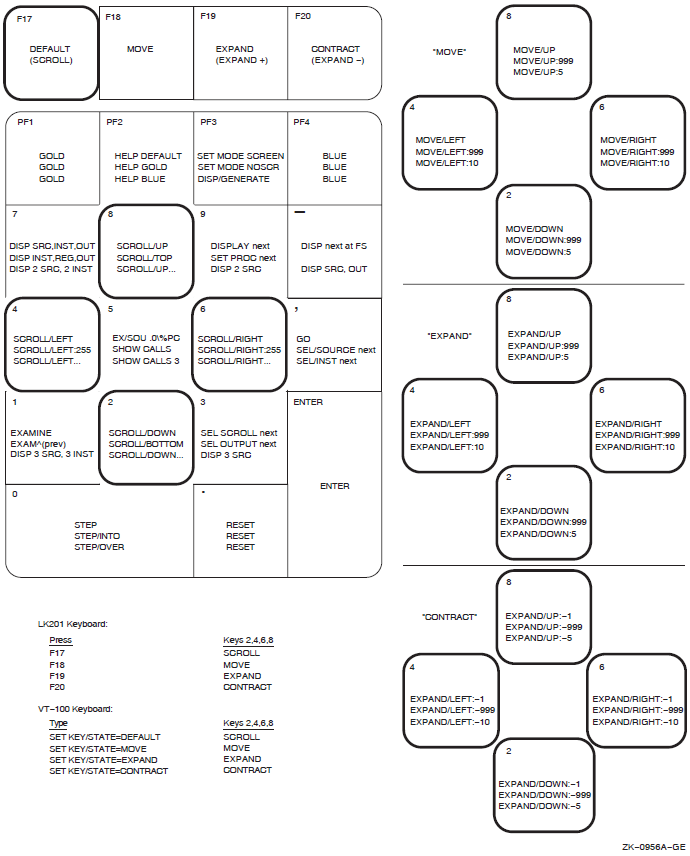

When you start the debugger, a few commonly used command sequences are automatically assigned to the keys on the numeric keypad (to the right of the main keyboard). Thus, you can perform certain functions either by entering a command or by pressing a keypad key.

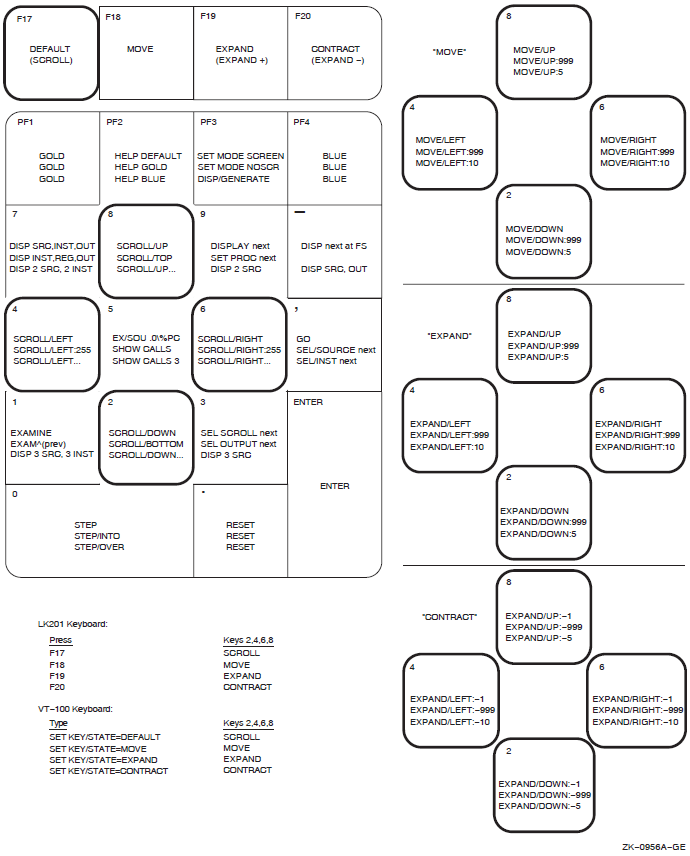

The predefined key functions are identified in Figure 2.1, ''Keypad Key Functions Predefined by the Debugger—Command Interface''.

To enter a key's DEFAULT function, press the key.

To enter its GOLD function, first press and release the PF1 (GOLD) key, and then press the key.

To enter its BLUE function, first press and release the PF4 (BLUE) key, and then press the key.

Pressing KP0 (keypad key 0) enters the STEP command.

Pressing PF1 KP0 enters the STEP /INTO command.

Pressing PF4 KP0 enters the STEP /OVER command.

Normally, keys KP2, KP4, KP6, and KP8 scroll screen displays down, left, right, or up,

respectively. By putting the keypad in the MOVE, EXPAND, or CONTRACT state, indicated in

Figure 2.1, ''Keypad Key Functions Predefined by the Debugger—Command Interface'', you can also use these keys to move, expand, or contract

displays in four directions. Enter the command HELP

Keypad_Definitions to display the keypad

key definitions.

2.2. Displaying Source Code

The debugger provides two modes for displaying information: noscreen mode and screen mode. By default, when you start the debugger, you are in noscreen mode, but you might find that it is easier to view source code in screen mode. The following sections briefly describe both modes.

2.2.1. Noscreen Mode

Noscreen mode is the default, line-oriented mode of displaying input and output. The interactive examples throughout this chapter, excluding Section 2.2.2, ''Screen Mode'', show noscreen mode.

DBG> TYPE 7

module SWAP_ROUTINES

7: TEMP := A;

DBG>DBG> TYPE TEST\16:21

Path names are discussed in more detail in Section 2.3.2, ''Executing the Program by Step Unit'', with the STEP command.

You can also use the EXAMINE /SOURCE command to display the source line for a routine or any other program location that is associated with an instruction.

The debugger also displays source lines automatically when it suspends execution at a breakpoint or watch point, after a STEP command, or when a trace point is triggered (see Section 2.3, ''Controlling and Monitoring Program Execution'').

After displaying source lines at various locations in your program, you can redisplay the location at which execution is currently paused by pressing KP5.

Execution is paused within a module that was compiled or linked without the /DEBUG qualifier.

Execution is paused within a system or shareable image routine for which no source code is available.

The source file was moved to a different directory after it was compiled (the location of source files is embedded in the object modules).In this case, use the SET SOURCE command to specify the new location.

The module might need to be set with the SET MODULE command. Module setting is explained in Section 2.5.1, ''Setting and Canceling Modules''.

To switch to noscreen mode from screen mode, press PF1 PF3 (or type SET MODE NOSCREEN). You can use the TYPE and EXAMINE /SOURCE commands in screen mode as well as noscreen mode.

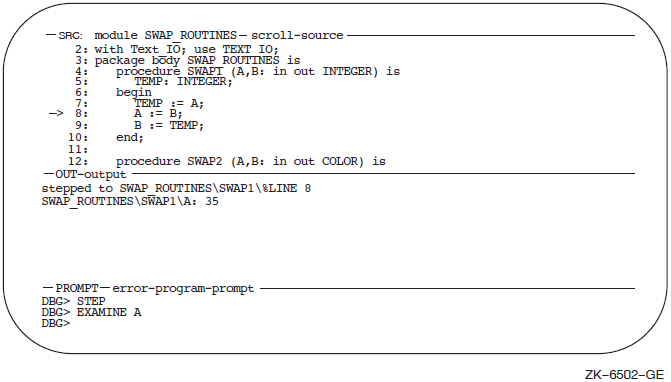

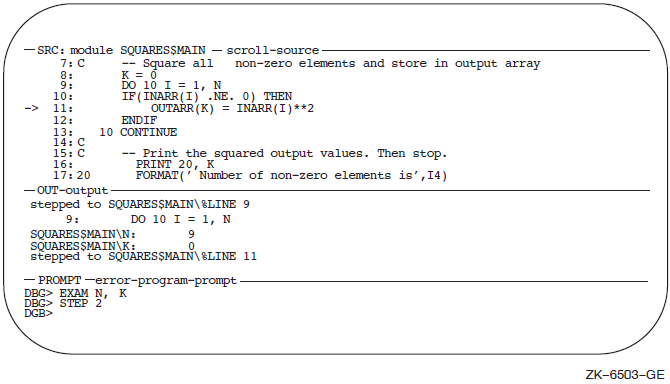

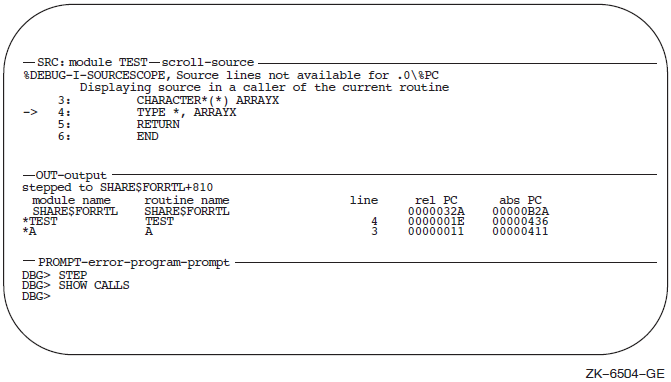

2.2.2. Screen Mode

Screen mode provides the easiest way to view your source code. To switch to screen mode, press PF3 (or type SET MODE SCREEN). In screen mode, by default the debugger splits the screen into three displays named SRC, OUT, and PROMPT, as shown in Figure 2.2, ''Default Screen Mode Display Configuration''.

|

The SRC display shows the source code of the module in which execution is currently paused. An arrow in the left column points to the source line corresponding to the current value of the program counter (PC). The PC is a register that contains the memory address of the instruction to be executed next. The line numbers, which are assigned by the compiler, match those in a listing file. As you execute the program, the arrow moves down and the source code is scrolled vertically to center the arrow in the display.

The OUT display captures the debugger's output in response to the commands that you enter. The PROMPT display shows the debugger prompt, your input (the commands that you enter), debugger diagnostic messages, and program output.

You can scroll both SRC and OUT to see whatever information might scroll beyond the display window's edge. Press KP3 repeatedly as needed to select the display to be scrolled (by default, SRC is scrolled). Press KP8 to scroll up and KP2 to scroll down. Scrolling a display does not affect program execution.

%DEBUG-I-SOURCESCOPE, Source lines not available for .0 \%PC.Displaying source in a caller of the current routine. DBG>

In such cases, the arrow in the SRC display identifies the line that contains code following the call statement in the calling routine.

2.3. Controlling and Monitoring Program Execution

Start and resume program execution

Execute the program to the next source line, instruction, or other step unit

Determine where execution is currently paused

Use breakpoints to suspend program execution at points of interest

Use trace points to trace the execution path of your program through specified locations

Use watchpoints to monitor changes in the values of variables

With this information you can pick program locations where you can then test and manipulate the contents of variables as described in Section 2.4, ''Examining and Manipulating Program Data''.

2.3.1. Starting or Resuming Program Execution

Use the GO command to start or resume program execution.

The program completes execution

A breakpoint is reached

A watchpoint is triggered

An exception is signaled

You press Ctrl/C

With most programming languages, when you bring a program under debugger control, execution is initially paused directly at the beginning of the main program. Entering a GO command at this point quickly enables you to test for an infinite loop or an exception.

If an infinite loop occurs during execution, the program does not terminate, so the debugger prompt does not reappear. To obtain the prompt, interrupt execution by pressing Ctrl/C (see Section 1.4, ''Interrupting Program Execution and Aborting Debugger Commands''). If you are using screen mode, the pointer in the source display indicates where execution stopped. You can also use the SHOW CALLS command to identify the currently active routine calls on the call stack (see Section 2.3.3, ''Determining Where Execution Is Paused'').

If an exception that is not handled by your program is signaled, the debugger interrupts execution at that point so that you can enter commands. You can then look at the source display and a SHOW CALLS display to find where execution is paused.

The most common use of the GO command is in conjunction with breakpoints, tracepoints, and watchpoints, as described in Section 2.3.4, ''Suspending Program Execution with Breakpoints'', Section 2.3.5, ''Tracing Program Execution with Tracepoints'', and Section 2.3.6, ''Monitoring Changes in Variables with Watchpoints'', respectively. If you set a breakpoint in the path of execution and then enter the GO command, execution is paused at that breakpoint. Similarly, if you set a tracepoint, execution is monitored through that tracepoint. If you set a watchpoint, execution is paused when the value of the watched variable changes.

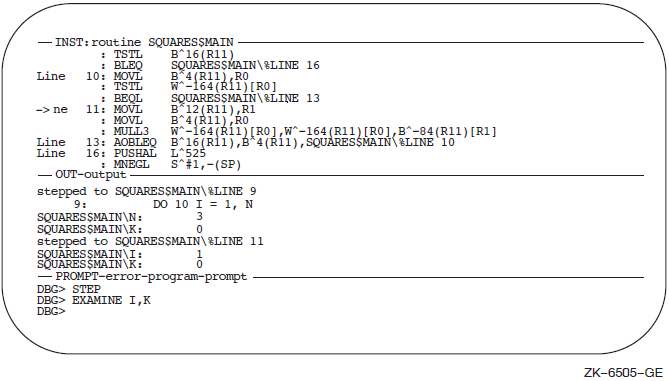

2.3.2. Executing the Program by Step Unit

Use the STEP command to execute the program one or more step units at a time.

DBG> STEP

stepped to TEST\COUNT\%LINE 27

27: X := X + 1;

DBG>Execution is now paused at the first machine-code instruction for line 27 within routine COUNT of module TEST.

When displaying a program symbol (for example, a line number, routine name, or variable name),

the debugger always uses a path name. A path name consists of

the symbol plus a prefix that identifies the symbol's location. In the previous

example, the path name is TEST \COUNT \%LINE27. The leftmost

element of a path name is the module name. Moving toward the right, the path name

lists any successively nested routines and blocks that enclose the symbol. A

backslash character (\) is used to separate elements (except when

the language is Ada, where a period is used to parallel Ada syntax).

A path name uniquely identifies a symbol of your program to the debugger. In general, you need to use path names in commands only if the debugger cannot resolve a symbol ambiguity in your program (see Section 2.5, ''Controlling Access to Symbols in Your Program''). Usually the debugger can determine the symbol you mean from its context.

When using the STEP command, note that only those source lines for which code instructions were generated by the compiler are recognized as executable lines by the debugger. The debugger skips over any other lines - for example, comment lines.

You can specify different stepping modes, such as stepping by instruction rather than by line (SET STEP INSTRUCTION). Also, by default, the debugger steps over called routines-execution is not paused within a called routine, although the routine is executed. By entering the SET STEP INTO command, you direct the debugger to suspend execution within called routines as well as within the routine in which execution is currently paused (SET STEP OVER is the default mode).

2.3.3. Determining Where Execution Is Paused

Use the SHOW CALLS command when you are unsure where execution is paused during a debugging session (for example, after a Ctrl/C interruption).

The name of the module that contains the routine

The name of the routine

The line number at which the call was made (or at which execution is paused, in the case of the current routine)

The corresponding PC value

On Alpha and Integrity server processors, the PC is shown as a memory address relative to the first code address in the module and also as an absolute address.

Note that on Integrity server processors, there is no hardware PC register. The PC is a software constructed value, built by adding the hardware Instruction Pointer (IP) register and the slot offset of the instruction within the bundle (0, 1, or 2).

DBG> SHOW CALLS module name routine name line rel PC abs PC *TEST PRODUCT 18 00000009 0000063C *TEST COUNT 47 00000009 00000647 *MY_PROG MY_PROG 21 0000000D 00000653 DBG>

This example indicates that execution is paused at line 18 of routine PRODUCT (in module TEST), which was called from line 47 of routine COUNT (in module TEST), which was called from line 21 of routine MY_PROG (in module MY_PROG).

2.3.4. Suspending Program Execution with Breakpoints

The SET BREAK command enables you to select locations at which to suspend program execution (breakpoints).You can then enter commands to check the call stack, examine the current values of variables, and so on. You resume execution from a breakpoint with the GO or STEP commands.

DBG> SET BREAK COUNT

DBG> GO

.

.

.

break at routine PROG2\COUNT

54: procedure COUNT(X, Y:INTEGER);

DBG>Execution is paused.

The debugger announces that the breakpoint at COUNT has been reached ("break at …").

The debugger displays the source line (54) at which execution is paused.

The debugger prompts for another command.

At this breakpoint, you can use the STEP command to step through routine COUNT and then use the EXAMINE command (discussed in Section 2.4.1, ''Displaying the Value of a Variable'') to check on the values of X and Y.

When using the SET BREAK command, you can specify program locations using various kinds of address expressions (for example, line numbers, routine names, memory addresses, byte offsets). With high-level languages, you typically use routine names, labels, or line numbers, possibly with path names to ensure uniqueness.

DBG> SET BREAK %LINE 41

DBG> SET BREAK SCREEN_IO\%LINE 58

DBG> SET BREAK/LINE DBG> SET BREAK/CALL

You can set breakpoints on events, such as exceptions, or state transitions in tasking programs.

You can conditionalize a breakpoint (with a WHEN clause)or specify that a list of commands be executed at the breakpoint (with a DO clause).

To display the current breakpoints, enter the SHOW BREAK command.

To deactivate a breakpoint, enter the DEACTIVATE BREAK command, and specify the program location exactly as you did when setting the breakpoint. This causes the debugger to ignore the breakpoint during program execution. However, you can activate it at a later time, for example, when you rerun the program (see Section 1.3.3, ''Rerunning the Same Program from the Kept Debugger''). A deactivated breakpoint is listed as such in a SHOW BREAK display.

To activate a breakpoint, use the ACTIVATE BREAK command. Activating a breakpoint causes it to take effect during program execution.

The commands DEACTIVATE BREAK/ALL and ACTIVATE BREAK/ALL operate on all breakpoints and are particularly useful when rerunning a program.

To cancel a breakpoint, use the CANCEL BREAK command. A canceled breakpoint is no longer listed in a SHOW BREAK display.

2.3.5. Tracing Program Execution with Tracepoints

The SET TRACE command enables you to select locations for tracing the execution of your program (tracepoints), without stopping its execution. After setting a tracepoint, you can start execution with the GO command and then monitor the path of execution, checking for unexpected behavior. By setting a tracepoint on a routine, you can also monitor the number of time sit is called.

DBG> SET TRACE COUNT

DBG> GO

trace at routine PROG2\COUNT

54: procedure COUNT(X, Y:INTEGER);

.

.

.This is the only difference between a breakpoint and a tracepoint. When using the SET TRACE command, you specify address expressions, qualifiers, and optional clauses exactly as with the SET BREAK command. The commands SHOW TRACE, ACTIVATE TRACE, DEACTIVATE TRACE, and CANCEL TRACE operate on tracepoints in a manner similar to the corresponding commands for breakpoints (see Section 2.3.4, ''Suspending Program Execution with Breakpoints'').

2.3.6. Monitoring Changes in Variables with Watchpoints

The SET WATCH command enables you to specify program variables that the debugger monitors as your program executes. This process is called setting watchpoints. If the program modifies the value of a watched variable, the debugger suspends execution and displays information. The debugger monitors watchpoints continuously during program execution. (Note that you can also use the SET WATCH command to monitor arbitrary program locations, not just variables.)

TOTAL:DBG> SET WATCH TOTAL

Note

The technique you use to set watchpoints depends on your system (Alpha or Integrity servers) and the type of variable, static or nonstatic. On Alpha systems, for example, a static variable is associated with the same memory address throughout program execution.

DBG> SET WATCH TOTAL

DBG> GO

.

.

.

watch of SCREEN_IO\TOTAL at SCREEN_IO\%LINE 13

13: TOTAL = TOTAL + 1;

old value: 16

new value: 17

break at SCREEN_IO\%LINE 14

14: POP(TOTAL);

DBG>In this example, a watchpoint is set on the variable TOTAL and execution is started. When the value of TOTAL changes, execution is paused. The debugger announces the event ("watch of …"), identifying where TOTAL changed (the beginning of line 13) and the associated source line. The debugger then displays the old and new values and announces that execution has been paused at the beginning of the next line (14). Finally, the debugger prompts for another command. When a change in a variable occurs at a point other than the beginning of a source line, the debugger gives the line number plus the byte offset from the beginning of the line.

On Alpha systems, you can set a watchpoint on a nonstatic variable by setting a tracepoint on the defining routine and specifying a DO clause to set the watchpoint whenever execution reaches the tracepoint. Since a nonstatic variable is allocated on the stack or in a register and exists only when its defining routine is active (on the call stack), the variable name is not always meaningful in the way that a static variable name is.

DBG> SET TRACE/NOSOURCE ROUT3 DO (SET WATCH Y)

DBG> GO

.

.

.

trace at routine MOD4\ROUT3

%DEBUG-I-WPTTRACE, nonstatic watchpoint, tracing every

instruction

.

.

.

watch of MOD4\ROUT3\Y at MOD4\ROUT3\%LINE 16

16: Y := 4

old value: 3

new value: 4

break at MOD4\ROUT3\%LINE 17

17: SWAP(X, Y);

DBG>When execution returns to the calling routine, the nonstatic variable is no longer active, so the debugger automatically cancels the watchpoint and issues a message to that effect.

On Alpha and Integrity servers, the debugger treats all watchpoints as nonstatic watchpoints.

The commands SHOW WATCH, ACTIVATE WATCH, DEACTIVATE WATCH, and CANCEL WATCH operate on watchpoints in a manner similar to the corresponding commands for breakpoints (see Section 2.3.4, ''Suspending Program Execution with Breakpoints''). However, a nonstatic watchpoint exists only as long as execution remains within the scope of the variable being watched.

2.4. Examining and Manipulating Program Data

This section explains how to use the EXAMINE, DEPOSIT, and EVALUATE commands to display and modify the contents of variables and evaluate expressions. Before you can examine or deposit into a nonstatic variable, as defined in Section 2.3.6, ''Monitoring Changes in Variables with Watchpoints'', its defining routine must be active.

2.4.1. Displaying the Value of a Variable

EXAMINE address-expressionThe debugger recognizes the compiler-generated data type of the variable you specify and retrieves and formats the data accordingly. The following examples show some uses of the EXAMINE command.

DBG> EXAMINE EMPLOYEE_NAME

PAYROLL\EMPLOYEE_NAME:

"Peter C. Lombardi"

DBG>DBG> EXAMINE WIDTH, LENGTH, AREA SIZE\WIDTH: 4 SIZE\LENGTH: 7 SIZE\AREA: 28 DBG>

DBG> EXAMINE REAL_ARRAY PROG2\REAL_ARRAY (1, 1): 27.01000 (1, 2): 31.00000 (1, 3): 12.48000 (2, 1): 15.08000 (2, 2): 22.30000 (2, 3): 18.73000 DBG>

DBG> EXAMINE CHAR_ARRAY(4) PROG2\CHAR_ARRAY(4): 'm' DBG>

DBG> EXAMINE PART

INVENTORY\PART:

ITEM: "WF-1247"

PRICE: 49.95

IN_STOCK: 24

DBG>DBG> EXAMINE IN_STOCK OF PART

INVENTORY\IN-STOCK of PART:

IN_STOCK: 24

DBG>You can use the EXAMINE command with any kind of address expression (not just a variable name) to display the contents of a program location. The debugger associates certain default data types with untyped locations. If you want the data interpreted and displayed in some other data format you can override the defaults for typed and untyped locations.

2.4.2. Assigning a Value to a Variable

DEPOSITaddress-expression=language-expression

The DEPOSIT command is like an assignment statement in most programming languages.

In the following examples, the DEPOSIT command assigns new values to different variables. The debugger checks that the value assigned, which can be a language expression, is consistent with the data type and dimensional constraints of the variable.

DBG> DEPOSIT PART_NUMBER = "WG-7619.3-84"

DBG> DEPOSIT WIDTH = CURRENT_WIDTH + 10

DBG> DEPOSIT C_ARRAY(12) := 'K'

DBG> DEPOSIT EMPLOYEE.ZIPCODE = 02172

DBG> DEPOSIT X = -14

%DEBUG-I-IVALOUTBNDS, value assigned is out of bounds

at or near DEPOSITAs with the EXAMINE command, you can specify any kind of address expression (not just a variable name) with the DEPOSIT command. You can override the defaults for typed and untyped locations if you want the data interpreted in some other data format.

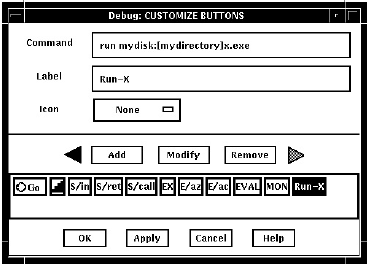

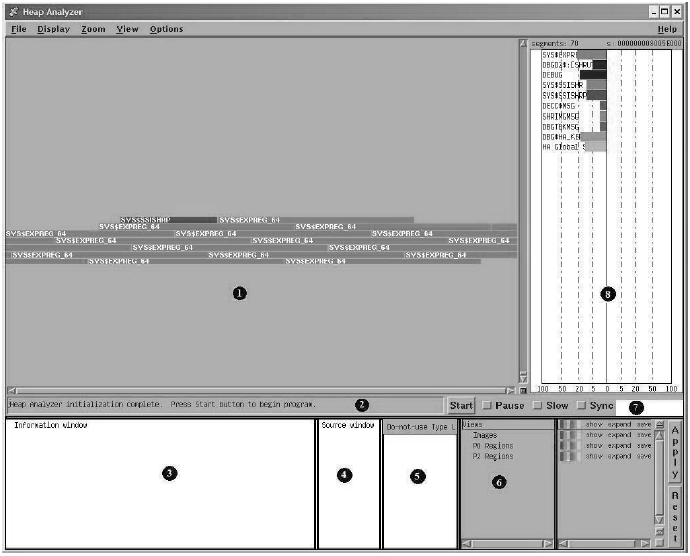

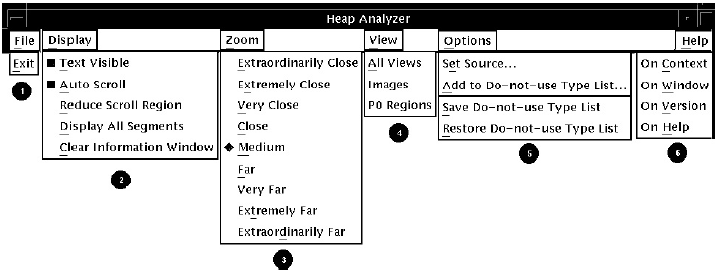

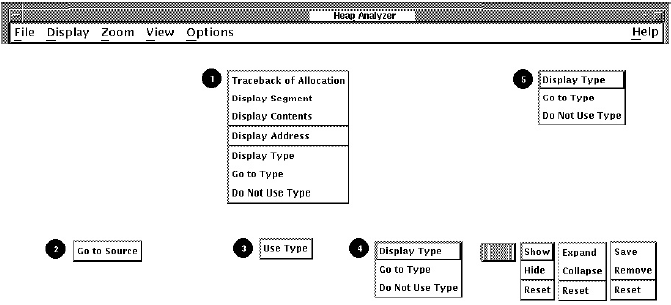

2.4.3. Evaluating Language Expressions