VSI Pascal Reference Manual

- Software Version:

- VSI Pascal Version 6.3 for OpenVMS x86-64

VSI Pascal Version 6.2 for OpenVMS IA-64

VSI Pascal Version 6.2 for OpenVMS Alpha

- Operating System and Version:

- VSI OpenVMS x86-64 Version 9.2-2 or higher

VSI OpenVMS IA-64 Version 8.4-1H1 or higher

VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 or higher

Preface

This manual describes the VSI Pascal programming language. It contains information on:

VSI Pascal language syntax and semantics

VSI Pascal adherence to Pascal standards

All references to OpenVMS systems refer to the OpenVMS IA-64, OpenVMS Alpha, and OpenVMS x86-64 operating systems unless otherwise specified.

1. About VSI

VMS Software, Inc. (VSI) is an independent software company licensed by Hewlett Packard Enterprise to develop and support the OpenVMS operating system.

2. Intended Audience

This manual is for experienced applications programmers with a basic understanding of the Pascal language. Some familiarity with your operating system is helpful. This is not a tutorial manual.

3. Document Structure

Chapter 1, "Language Elements" describes Pascal language standards and lexical elements.

Chapter 2, "Data Types and Values" describes data types and values.

Chapter 3, "Declaration Section" describes declaration sections.

Chapter 4, "Expressions and Operators" describes expressions and operators.

Chapter 5, "Statements" describes statements.

Chapter 6, "Procedures and Functions" describes user-written procedures and functions.

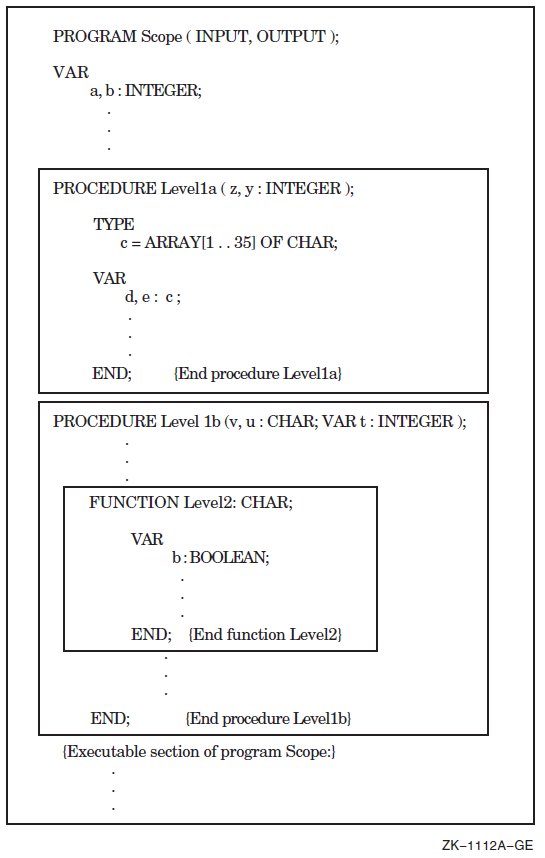

Chapter 7, "Program Structure and Scope" describes program structure and scope.

Chapter 8, "Predeclared Functions and Procedures" describes predeclared procedures and functions, except those that perform input and output.

Chapter 9, "Input and Output Processing" describes the predeclared procedures and functions that perform input and output.

Chapter 10, "Attributes" describes attributes.

Chapter 11, "Directives" describes directives.

Appendix A, "Data Storage and Representation" describes the storage allocation and alignment for data types and the internal representation of each data type.

Appendix B, "Summary of VSI Pascal for OpenVMS Extensions" describes the VSI Pascal extensions to the Pascal standards.

Appendix C, "Description of Implementation Features" describes the VSI Pascal implementation features that the Pascal standards allow each implementation to define.

Appendix D, "Compiler and Run-Time System Error Detection" describes how the VSI Pascal compiler detects errors defined by the Pascal standard.

4. Related Documents

VSI Pascal User Manual—Provides information about programming tasks, about using features in conjunction with one another, and about increasing the efficiency of program execution.

VSI Pascal Installation Guide—Provides information on how to install VSI Pascal on your operating system.

5. VSI Encourages Your Comments

You may send comments or suggestions regarding this manual or any VSI document by sending electronic mail to the following Internet address: <docinfo@vmssoftware.com>. Users who have VSI OpenVMS support contracts through VSI can contact <support@vmssoftware.com> for help with this product.

6. OpenVMS Documentation

The full VSI OpenVMS documentation set can be found on the VMS Software Documentation webpage at https://docs.vmssoftware.com.

7. Conventions

The following conventions are used in this manual:

|

Convention |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

Ctrl/x |

A sequence such as Ctrl/x indicates that you must hold down the key labeled Ctrl while you press another key or a pointing device button. |

| PF1 x |

A sequence such as PF1 x indicates that you must first press and release the key labeled PF1 and then press and release another key or a pointing device button. |

... |

A horizontal ellipsis in examples indicates one of the

following possibilities:

|

. . . |

A vertical ellipsis indicates the omission of items from a code example or command format; the items are omitted because they are not important to the topic being discussed. |

| ( ) |

In command format descriptions, parentheses indicate that you must enclose choices in parentheses if you specify more than one. |

| [ ] | In command format descriptions, brackets indicate optional choices. You can choose one or more items or no items. Do not type the brackets on the command line. However,you must include the brackets in the syntax for OpenVMS directory specifications and for a substring specification in an assignment statement. |

| | | In command format descriptions, vertical bars separate choices within brackets or braces. Within brackets, the choices are optional; within braces, at least one choice is required. Do not type the vertical bars on the command line. |

| { } |

In command format descriptions, braces indicate required choices; you must choose at least one of the items listed. Do not type the braces on the command line. |

| bold type |

Bold type represents the name of an argument, an attribute, or a reason. |

| italic type | Italic type indicates important information, complete titles of manuals, or variables. Variables include information that varies in system output (Internal error number), in command lines (/PRODUCER=name), and in command parameters in text (where dd represents the predefined code for the device type). |

| UPPERCASE TYPE |

Uppercase type indicates a command, the name of a routine, the name of a file, or the abbreviation for a system privilege. |

- |

A hyphen at the end of a command format description, command line, or code line indicates that the command or statement continues on the following line. |

| numbers |

All numbers in text are assumed to be decimal unless otherwise noted. Nondecimal radixes – binary, octal, or hexadecimal – are explicitly indicated. |

Chapter 1. Language Elements

1.1. Pascal Language Standards

The VSI Pascal compiler accepts programs that comply with two standards and a subset of programs that comply with a third. VSI Pascal also provides features (called extensions) that are not part of any standard. For portable code, limit your use of these extensions or isolate the extensions in separate modules.

1.1.1. Unextended Pascal Standards

American National Standard ANSI/IEEE770X3.97-1989 (ANSI)

International Standard ISO 7185-1989 (ISO)

VSI Pascal accepts programs that comply to either standard. In the VSI Pascal documentation set, the term "unextended Pascal" applies to both the ANSI and ISO standards.

VSI Pascal contains FIPS-109 (Federal Information Processing Standard) validation support.

The standards are divided into two levels of standardization: Level 0 and Level 1. An example of a technical difference between the Level 0 standard and the Level 1 standard is that Level 0 does not include conformant arrays, while Level 1 does.

VSI Pascal has passed the validation suite for Pascal compilers. It received a CLASS A certificate for both levels of the ISO standard as well as the ANSI standard. CLASS A certificates are given to compilers with a fully conforming implementation.

For More Information:

On VSI Pascal extensions to unextended Pascal (Appendix B, "Summary of VSI Pascal for OpenVMS Extensions")

On VSI Pascal implementation-dependent features (Appendix C, "Description of Implementation Features")

On VSI Pascal error processing as defined by the standards (Appendix D, "Compiler and Run-Time System Error Detection")

On flagging nonstandard constructs during compilation (VSI Pascal User Manual)

1.1.2. Extended Pascal Standard

American National Standard ANSI/IEEE770X3.160-1989

International Standard ISO 10206-1989

In the VSI Pascal documentation set, the term Pascal standard refers to these standards. Because VSI Pascal supports most Extended Pascal standard features, it cannot compile all programs that comply with Extended Pascal.

For More Information:

On VSI Pascal support for Extended Pascal features (Appendix B, "Summary of VSI Pascal for OpenVMS Extensions")

On flagging nonstandard constructs during compilation (VSI Pascal User Manual)

1.2. Lexical Elements

This section discusses lexical elements of the VSI Pascal language.

1.2.1. Character Set

Uppercase letters A through Z and lowercase letters a through z

Integers 0 through 9

Special characters, such as the ampersand (&), question mark (?), and equal sign (=)

Nonprinting characters, such as the space, tab, line feed, carriage return, and form feed (use of these characters can improve the legibility of your programs)

Extended, unspecified characters with numeric codes from 128 to 255

Each ASCII character corresponds to a numeric value.

Each element of the character set is a constant of the predefined VSI Pascal type CHAR. An ASCII decimal number is the same as the ordinal value (as returned by the Pascal ORD function) of the associated character in the type CHAR.

VSI Pascal allows full use of eight-bit characters.

PROGRAM PRogrAm program

'b' 'B' "c" "C"

1.2.2. Special Symbols

|

Symbol |

Name |

Symbol |

Name |

|---|---|---|---|

|

' |

Apostrophe |

<= |

Less than or equal to |

|

:= |

Assignment operator |

- |

Minus sign |

|

[ ] or (. .) |

Brackets |

* |

Multiplication |

|

: |

Colon |

<> |

Not equal |

|

, |

Comma |

( ) |

Parentheses |

|

(* *) or { } |

Comments |

% |

Percent |

|

/ |

Division |

. |

Period |

| " |

Double quote |

+ |

Plus sign |

|

= |

Equal sign |

^ or @ |

Pointer |

|

** |

Exponentiation |

; |

Semicolon |

|

> |

Greater than |

.. |

Subrange operator |

|

>= |

Greater than or equal to |

:: |

Type cast operator |

|

< |

Less than |

1.2.3. String Delimiters

VSI Pascal accepts single-quote and double-quote characters as string and character delimiters.

1.2.4. Embedded String Constants

|

Constant |

Definition |

ASCII Value |

|---|---|---|

|

\a |

Bell character |

16#7 |

|

\b |

Backspace character |

16#8 |

|

\f |

Form-feed character |

16#C |

|

\n |

Line-feed character |

16#A |

|

\r |

Carriage-return character |

16#D |

|

\t |

Horizontal tab character |

16#9 |

|

\v |

Vertical character |

16#B |

|

\ \ |

Backslash character |

16#5C |

|

\" |

Double-quotation character |

16#22 |

|

\' |

Single-quotation character |

16#27 |

|

\nnn |

Character whose value is nnn |

nnn is an octal number from 000 to 377. Leading zeros can be omitted. |

|

\xnn |

Character whose value is nn |

nn is a hexadecimal number from 00 to FF. Leading zeros can be omitted. |

1.2.5. Reserved Words

|

%DESCR |

%DICTIONARY |

%IMMED |

%INCLUDE |

|

%REF |

%STDESCR |

%SUBTITLE |

%TITLE |

|

AND |

ARRAY |

BEGIN |

CASE |

|

CONST |

DIV |

DO |

DOWNTO |

|

ELSE |

END |

FILE |

FOR |

|

FUNCTION |

GOTO |

IF |

IN |

|

LABEL |

MOD |

NIL |

NOT |

|

OF |

OR |

PACKED |

PROCEDURE |

|

PROGRAM |

RECORD |

REPEAT |

SET |

|

THEN |

TO |

TYPE |

UNTIL |

|

VAR |

WHILE |

WITH |

The manuals in the VSI Pascal documentation set show these reserved words in uppercase letters. If you choose, you can express them in mixed case or lowercase in your programs.

|

AND_THEN |

BREAK |

CONTINUE |

MODULE |

|

OR_ELSE |

OTHERWISE |

REM |

RETURN |

|

VALUE |

VARYING |

Note

This table does not include statements that are only provided by VSI Pascal for compatibility with other Pascal compilers.

This manual shows redefinable reserved words in uppercase letters. If you choose, you can express them in mixed case or lowercase in your programs.

1.2.6. Identifiers

An identifier cannot start with a digit.

An identifier cannot contain spaces or special symbols.

The first 31 characters of an identifier must denote a unique name within the block in which the identifier is declared. An identifier longer than 31 characters generates a warning message. The compiler ignores characters beyond the thirty-first character

The Pascal standard dictates that an identifier cannot start or end with an underscore, nor can two adjacent underscores be used within an identifier. However, VSI Pascal allows both cases of underscore use and generates an informational message if you compile with the standard switch.

On VSI OpenVMS systems, VSI Pascal uses uppercase characters for all external user symbols by default.

If you wish to use mixed-case names for externals symbols, use the GLOBAL or EXTERNAL attribute with a quoted string. VSI Pascal passes the string unmodified to the linker.

This manual shows predeclared identifiers in uppercase letters. If you choose, you can express them in mixed case or lowercase in your programs. The following examples show valid and invalid identifiers:

Valid:

For2n8

MAX_WORDS

upto

LOGICAL_NAME_TABLE {Unique in first}

Logical_Name_Scanner { 31 characters}

SYS$CREMBXInvalid:

4Awhile {Starts with a digit}

up&to {Contains an ampersand}

YEAR_END_87_MASTER_FILE_TOTAL_DISCOUNT {Not unique in first}

Year_End_87_Master_File_Total_Dollars { 31 characters}| ABS |

ADD_ATOMIC |

ADD_INTERLOCKED |

ADDRESS |

|

AND_ATOMIC |

ARCTAN |

ARGC |

ARGUMENT |

|

ARGUMENT_LIST_ |

ARGV |

ASSERT | |

|

BARRIER |

BIN |

BIT_OFFSET |

BITNEXT |

|

BITSIZE |

BOOLEAN |

BYTE_OFFSET | |

|

CARD |

CARDINAL |

CARDINAL16 |

CARDINAL32 |

|

CHAR |

CHR |

CLEAR_ |

CLOCK |

|

C_STR |

C_STR_T |

CLOSE |

COS |

|

CREATE_DIRECTORY | |||

|

D_FLOAT |

DATE |

DBLE |

DEC |

|

DELETE |

DELETE_FILE |

DISPOSE |

DOUBLE |

|

EOF |

EOLN |

EPSDOUBLE |

EPSQUADRUPLE |

|

EPSREAL |

EQ |

ESTABLISH |

EXP |

|

EXPO |

EXTEND | ||

|

F_FLOAT |

FALSE |

FIND |

FIND_FIRST_BIT_ |

|

FIND_FIRST_BIT_SET |

FIND_MEMBER |

FIND_NONMEMBER |

FINDK |

|

G_FLOAT |

GE |

GET |

GETTIMESTAMP |

|

GT | |||

|

H_FLOAT |

HALT |

HEX | |

|

IADDRESS |

IADDRESS64 |

INDEX |

INPUT |

|

INT |

INTEGER |

INTEGER8 |

INTEGER16 |

|

INTEGER32 |

INTEGER64 |

INTEGER_ADDRESS | |

|

LE |

LENGTH |

LINELIMIT |

LN |

|

LOCATE |

LOWER |

LSHIFT |

LT |

|

MALLOC_C_STR |

MAX |

MAXCHAR |

MAXDOUBLE |

|

MAXINT |

MAXQUADRUPLE |

MAXREAL |

MAXUNSIGNED |

|

MIN |

MINDOUBLE |

MINQUADRUPLE |

MINREAL |

|

NE |

NEW |

NEXT |

NIL |

|

OCT |

ODD |

OPEN |

OR_ATOMIC |

|

ORD |

OUTPUT | ||

|

PACK |

PAD |

PAGE |

PAS_STR |

|

PAS_STRCPY |

POINTER |

PRED |

PRESENT |

|

PUT | |||

|

QUAD |

QUADRUPLE | ||

|

RANDOM |

READ |

READLN |

READV |

|

REAL |

RENAME_FILE |

RESET |

RESETK |

|

REVERT |

REWRITE |

ROUND |

ROUND64 |

|

RSHIFT | |||

|

S_FLOAT |

SEED |

SET_INTERLOCKED |

SIN |

|

SINGLE |

SIZE |

SNGL |

SQR |

|

SQRT |

STATUS |

STATUSV |

STRING |

|

SUBSTR |

SUCC |

SYSCLOCK | |

|

T_FLOAT |

TEXT |

TIME |

TIMESTAMP |

|

TRUE |

TRUNC |

TRUNC64 |

TRUNCATE |

|

UAND |

UDEC |

UFB |

UINT |

|

UNDEFINED |

UNLOCK |

UNOT |

UNPACK |

|

UNSIGNED |

UNSIGNED8 |

UNSIGNED16 |

UNSIGNED32 |

|

UNSIGNED64 |

UOR |

UPDATE |

UPPER |

|

UROUND |

UROUND64 |

UTRUNC |

UTRUNC64 |

|

UXOR | |||

|

WALLCLOCK |

WRITE |

WRITELN |

WRITEV |

|

X_FLOAT |

XOR | ||

|

ZERO |

Note

This table does not include predefined identifiers that are only provided by VSI Pascal for compatibility with other Pascal compilers.

For More Information:

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

1.3. Comments

Comments document the actions or elements of a program. The text of a comment can contain any ASCII character except a nonprinting control character, such as an ESCAPE character. You can place comments anywhere in a program that white space can appear.

{ This is a comment. }

(* This is a comment, too. *){ The delimiters of this comment do not match. *)

(* VSI Pascal allows you to mix delimiters in this way. }(* Cannot { nest comments inside } of comments like this *)%IF FALSE %THEN ...code to disable... %ENDIF

For more information on %IF, see Section 11.4, ''%IF, %ELSE, %ELIF, and %ENDIF''.

VSI Pascal allows for an end-of-line comment using an exclamation point (!). If an exclamation point is encountered on a line in the source program, the remainder of that line will be treated as a comment.

This comment syntax is not recognized by SCA for report generation.

1.4. Page Breaks and Form Feeds in Programs

FF %TITLE 'Variable Declarations' end; FF FF FF VAR FF

BEGIN FF ENDThe page break does not affect the meaning of the program, but causes a page to eject at the corresponding line in a listing file.

Chapter 2. Data Types and Values

Every piece of data that is created or manipulated by an VSI Pascal program has a data type. The data type determines the range of values, set of valid operations, and maximum storage allocation for each piece of data.

Ordinal types (Section 2.1, ''Ordinal Types'')

Real types (Section 2.2, ''Real Types'')

Pointer types (Section 2.3, ''Pointer Types'')

Structured types (Section 2.4, ''Structured Types'')

Schema types (Section 2.5, ''Schema Types'')

String schemas and types (Section 2.6, ''String Types'')

Predefined TIMESTAMP type (Section 2.8, ''TIMESTAMP Type'')

Static and nonstatic types (Section 2.9, ''Static and Nonstatic Types'')

Rules of type compatibility (Section 2.10, ''Type Compatibility'')

For More Information:

On user-defined types and the TYPE section (Section 3.5, ''TYPE Section'')

On variable declarations and the VAR section (Section 3.7, ''VAR Section'')

On automatic type conversions (Section 4.4, ''Type Conversions'')

On type conversion functions (Chapter 8, "Predeclared Functions and Procedures")

Internal representation of data types (Section A.3, ''Internal Representation of Data Types'')

2.1. Ordinal Types

This section describes the ordinal types that are predefined by VSI Pascal and user-defined ordinal types (types that require you to provide identifiers or boundary values to completely define the data type).

The ranges of values for these types are ordinal in nature; the values are ordered so that each has a unique ordinal value indicating its position in a list of all the values of that type. There is a one-to-one correspondence between the values in an ordinal type and the set of positive integers.

2.1.1. Integer Types

VSI Pascal makes available the INTEGER, INTEGER64, UNSIGNED, UNSIGNED64, and INTEGER_ADDRESS predeclared types. These data types are described in Section 2.1.1.1, ''INTEGER and INTEGER64 Types'', Section 2.1.1.2, ''UNSIGNED and UNSIGNED64 Types'', and Section 2.1.1.4, ''INTEGER_ADDRESS Type'', respectively.

2.1.1.1. INTEGER and INTEGER64 Types

VSI Pascal provides the INTEGER and INTEGER64 integer types. Also provided are the INTEGER8, INTEGER16, and INTEGER32 types, which are used as synonyms for subranges of the INTEGER type.

The range of the integer values consists of positive and negative integer values, and of the value 0. The range boundaries depend on the architecture of the machine you are using.

|

Data Type |

Size |

Range |

|---|---|---|

|

INTEGER8 |

8 bits |

-128..127 16#80..16#7F |

|

INTEGER16 |

16 bits |

-32768..32767 16#8000..16#7FFF |

|

INTEGER32 |

32 bits |

-2147483648..2147483647 16#80000000..16#7FFFFFFF |

|

INTEGER64 |

64 bits |

|

The largest possible value of the INTEGER64 type is represented by the predefined constant MAXINT64. The smallest possible value of the INTEGER64 type is represented by the value of the expression -MAXINT64. While the value of -MAXINT64-1 can also be represented, correct results may not be produced in certain expressions.

The largest possible value of the INTEGER type is represented by the predefined constant MAXINT. The smallest possible value of the INTEGER type is represented by the value of the expression -MAXINT. While the value -MAXINT-1 can also be represented, it may not produce correct results in certain expressions.

|

Constant |

Size |

Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MAXINT |

32 bits |

(231)-1 |

16#7FFFFFFF |

|

MAXINT64 |

64 bits |

(263)-1 |

16#7FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF |

2.1.1.2. UNSIGNED and UNSIGNED64 Types

VSI Pascal provides the UNSIGNED and UNSIGNED64 types. Also provided are the UNSIGNED32, CARDINAL, CARDINAL16, and CARDINAL32 types, which are used as synonyms for subranges of the UNSIGNED type. UNSIGNED8 and UNSIGNED16 are provided as synonyms for subranges of INTEGER with positive values that correspond to an UNSIGNED subrange of the same size. The range of unsigned values consists of nonnegative integer values.

The unsigned data types are VSI Pascal extensions that are provided to facilitate systems programming using certain operating systems. Given that these data types are not standard, you should not use them for every application involving nonnegative integers.

|

Data Type |

Size |

Range |

|---|---|---|

|

UNSIGNED8 |

8 bits |

0..255 0..16#FF |

|

UNSIGNED16, CARDINAL16 |

16 bits |

0..65535 (216-1) 0..16#FFFF |

|

UNSIGNED32, CARDINAL32 |

32 bits |

0..4294967295 (232)-1 0..16#FFFFFFFF |

|

UNSIGNED64 |

64 bits |

0..18446744073709551615 (264-1) 0..16#FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF |

The largest possible value of the UNSIGNED64 type is represented by the predefined constant MAXUNSIGNED64. The smallest possible value of the UNSIGNED64 type is 0.

|

Constant |

Size |

Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MAXUNSIGNED |

32 bits |

(232)-1 |

16#FFFFFFFF |

|

MAXUNSIGNED64 |

64 bits |

(264)-1 |

16#FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF |

2.1.1.3. Integer Literals

{ decimal-number }

{ base-number#[[']]extended-digit[[']] }

{- } { }

[[ { } ]] { {b } }

{+ } { % {o } [[']]extended-digit[[']] }

{ { } }

{ {x } }

{ }decimal-number 17 0 89324

base-number Specifies the base, or radix, of the number. VSI Pascal accepts numbers in bases 2 through 36.

extended-digit Specifies the notation that is appropriate for the specified base.

b o x Specifies an integer in either binary (base 2), octal (base 8), or hexadecimal (base 16) notation. In VSI Pascal you can use either uppercase or lowercase letters to specify the extended-digit notation.

You can use extended-digit notation in the same way you use the conventional integer notation. The one restriction is that you cannot use extended-digit values as labels.

VSI Pascal allows the use of spaces and tabs to make the extended-digit notation easier to read. To use spaces and tabs, enclose the extended digit in single quotation marks ( ’ ’).

2#10000011 2#'1000 0011' 32#1J -16#'7FFF FFFF'

%b'1000 0011' %O'7712' -%x'DEC'When VSI Pascal processes an integer constant, its type is based on its apparent value. Table 2.5, ''Data Types for Integer Constants'' and Table 2.5, ''Data Types for Integer Constants'' describe the type that is chosen for the integer constant.

|

Range of Integer Values |

Data Type |

|---|---|

|

- MAXINT64...( - MAXINT) -1 |

INTEGER64 |

|

- MAXINT...MAXINT |

INTEGER |

|

MAXINT+1...MAXINT64 |

INTEGER64 |

|

MAXINT64+1...MAXUNSIGNED64 |

UNSIGNED64 |

To force an INTEGER constant to become UNSIGNED, INTEGER64, or UNSIGNED64, you can use the UINT, INT64, or the UINT64 predeclared routines, respectively.

To force an UNSIGNED constant to become INTEGER64 or UNSIGNED64, you can use the INT64 or UINT64 predeclared routines, respectively.

To force an INTEGER64 constant to become UNSIGNED64, you can use the UINT64 predeclared routine.

For More Information:

On unary operators (Section 4.2, ''Operators'')

On built-in routines (Chapter 8, "Predeclared Functions and Procedures")

2.1.1.4. INTEGER_ADDRESS Type

The INTEGER_ADDRESS data type has the same underlying size as a pointer. INTEGER_ADDRESS is equivalent to the INTEGER data type.

For More Information:

On INTEGER notations (Section 2.1.1.1, ''INTEGER and INTEGER64 Types'')

On the IADDRESS function (Chapter 8, "Predeclared Functions and Procedures")

2.1.2. CHAR Type

The CHAR data type consists of single character values from the ASCII character set. The largest possible value of the CHAR type is the predefined constant MAXCHAR.

'A'

'z'

'0' { This is the character 0, not the integer value 0 }

'''' { The apostrophe or single quotation mark }

'?'"A"

"z"

"\"" { The double quotation mark }

"?"The ORD function accepts parameters of type CHAR. The function return value is the ordinal value of the character in the ASCII character set.

''(7) CHR( 7 )

"\n"

For More Information:

On the ORD function (Section 8.63, ''ORD Function'')

On the CHR function (Section 8.18, ''CHR Function'')

On the ASCII character set (Section 1.2.1, ''Character Set'')

On character strings (Section 2.6, ''String Types'')

On using escape sequences within double quotation marks for nonprinting characters (Section 1.2.4, ''Embedded String Constants'')

2.1.3. BOOLEAN Type

Boolean values are the result of testing relationships for truth or validity. The BOOLEAN data type consists of the two predeclared identifiers FALSE and TRUE. The expression ORD( FALSE ) results in the value 0; ORD( TRUE ) returns the integer 1.

The relational operators operate on the ordinal, real, string, or set expressions, and produce a Boolean result.

For More Information:

On the ORD function (Section 8.63, ''ORD Function'')

On relational operators (Section 4.2.2, ''Relational Operators'')

2.1.4. Enumerated Types

An enumerated type is a user-defined ordered set of constant values specified by identifiers. It has the following form:

({enumerated-identifier},...) enumerated-identifier The identifier of the enumerated type being defined. VSI Pascal allows a maximum of 65,535 identifiers in an enumerated type.

TYPE

Seasons = ( Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter );

VAR

Some_Seasons : Seasons VALUE Winter; {Initialized}In this enumerated type, Spring (value 0) and Summer (value 1) are less than Fall (value 2) because they precede Fall in the list of constant values. Winter (value 3) is greater than Fall because it follows Fall.

The ORD function accepts expressions of an enumerated type.

TYPE Seasons2 = ( Fall, Winter, Spring );

This enumerated type cannot be defined in the same block as the previous type, because the identifiers Spring, Fall, and Winter would not be unique.

For More Information:

On the ORD function (Section 8.63, ''ORD Function'')

2.1.5. Subrange Types

A subrange type is user-defined and specifies a limited portion of another ordinal type (called the base type). It has the following form:

lower-bound..upper-bound lower-bound A constant expression or a formal discriminant identifier that establishes the lower limit of the subrange.

upper-bound A constant expression or formal discriminant identifier that establishes the upper limit of the subrange. The value of the upper bound must be greater than or equal to the value of the lower bound.

The base type can be any enumerated or predefined ordinal type. The values in the subrange type appear in the same order as they are in the base type. For example, the result of the ORD function applied to a value of a subrange type is the ordinal value that is associated with the relative position of the value in the base type, not in the subrange type.

You can use a subrange type anywhere in a program that its base type is legal. A value of a subrange type is converted to a value of its base type before it is used in an operation. All rules that govern the operations performed on an ordinal type pertain to subranges of that type.

TYPE

Day = ( Mon, Tues, Wed, Thur, Fri, Sat, Sun );

Weekday = Mon..Fri; {subrange of base type Day}

Weekend = Sat..Sun; {subrange of base type Day}

Digit = '0'..'9'; {subrange of base type CHAR}

Month = 1..31; {subrange of base type INTEGER}

National Debt = 1..92233720368 {subrange of base type INTEGER64}

5477580;type word = [word] 0..65535; procedure take_a_word( p : word ); begin writeln(p); end; begin take_a_word(90000); end.

procedure take_a_word( p_ : integer );

var p : word; { Local copy }

begin

p := p_; { Make local copy and do range check from longword

integer expression into word subrange on assignment }

writeln(p);

end;This means that VSI Pascal will fetch an entire longword from P_ when making the local copy. If you call Pascal functions from non-Pascal routines with value parameters that are subranges, you must pass the address of a value with the size of the base type. If subrange checking is disabled, the compiler can assume that the actual parameter is in range and can only fetch a word since that is sufficient to represent all valid values.

If the parameter was a VAR parameter, then the compiler would indeed only fetch a word since the formal parameter is an alias for the actual parameter and you are not allowed to pass expressions to a VAR parameter. The compiler assumes that the VAR parameter contains a valid value of the subrange. In other words, subranges are checked at assignment time and are considered valid when fetched.

For More Information:

On ordinal types (Section 2.1, ''Ordinal Types'')

On compile-time and run-time expressions (Section 4.1, ''Expressions'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

On predeclared routines (Chapter 8, "Predeclared Functions and Procedures")

On using schema types (VSI Pascal User Manual)

On the ORD function (Section 8.63, ''ORD Function'')

On the TYPE section (Section 3.5, ''TYPE Section'')

On discriminant identifiers in subranges (Section 2.5, ''Schema Types'')

On using the CHECK attribute for subrange checking (Section 10.2.8, ''CHECK'')

2.2. Real Types

VSI Pascal predefines the REAL, SINGLE, DOUBLE, and QUADRUPLE data types in the floating-point formats listed in Table 2.6, ''Supported Floating-Point Formats''.

|

Data Type |

Format |

Precision |

Default on |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Single-precision REAL types? |

VAX F_floating-point format? |

1 part in 223 = 7 decimal digits |

VSI OpenVMS Alpha |

|

IEEE S_floating-point format |

1 part in 223 = 7 decimal digits |

VSI OpenVMS I64 | |

|

Double-precision DOUBLE types? |

1 part 255 = 16 decimal digits |

VSI OpenVMS x86-64 | |

|

VAX G_floating-point format? |

1 part in 252 = 15 decimal digits |

VSI OpenVMS Alpha | |

|

IEEE T_floating-point format |

1 part in 252 = 15 decimal digits |

VSI OpenVMS I64 | |

|

QUADRUPLE |

IEEE X_floating-point format |

1 part in 2112 = 33 decimal digits |

All OpenVMS systems |

VSI Pascal provides the following built-in data types to declare variables of a specific floating point type regardless of the /FLOAT setting on the command line (or FLOAT attribute on the MODULE):

F_FLOAT

D_FLOAT

G_FLOAT

S_FLOAT

T_FLOAT

X_FLOAT

To express REAL numbers, you can use either decimal or exponential notation. To express DOUBLE or QUADRUPLE numbers, you must use exponential notation.

2.4 893.2497 8.0 0.0

2.3E2 10.0E-1 9.14159e0

|

Letters |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

E or e |

Single-precision real number. The integer exponent following this letter specifies the power of 10. |

|

D or d |

Double-precision real number. All double-precision numbers in your program must appear in this exponential format; otherwise, the compiler reverts to single-precision representation. |

|

Q or q |

Quadruple-precision real number. All quadruple-precision numbers in your program must appear in this exponential format; otherwise, the compiler reverts to single-precision format. On systems that do not support the quadruple data type, the letters Q and q are treated as double-precision numbers (D). |

To express negative real numbers in exponential notation, use the negation operator (-). Remember that a negative real number such as -4.5E+3 is not a constant, but is actually an expression consisting of the negation operator (-) and the real number 4.5E+3. Use caution when expressing negative real numbers in complex expressions.

The floating lexical functions %F_FLOAT, %D_FLOAT, %G_FLOAT, %S_FLOAT, and %T_FLOAT can be prefixed on a floating constant to select the floating type regardless of any module-level attribute or command line selection.

| Identifier | Value |

|---|---|

|

Single-Precision F_floating | |

|

MINREAL |

2.938736E-39 |

|

MAXREAL |

1.701412E+38 |

|

EPSREAL? |

1.192093E-07 |

|

IEEE Single-Precision S_floating | |

|

MINREAL |

1.175494E-38 |

|

MAXREAL |

3.402823E+38 |

|

EPSREAL |

1.192093E-07 |

|

Double-Precision D_floating | |

|

MINDOUBLE |

2.938735877055719E-39 |

|

MAXDOUBLE |

1.701411834604692E+38 |

|

EPSDOUBLE |

2.22044604925031E-16? |

|

Double-Precision G_floating | |

|

MINDOUBLE |

5.56268464626800E-309 |

|

MAXDOUBLE |

8.98846567431158E+307 |

|

EPSDOUBLE |

2.22044604925031E-016 |

|

IEEE Double-Precision T_floating | |

|

MINDOUBLE |

2.2250738585072014E-308 |

|

MAXDOUBLE |

1.7976931348623157E+308 |

|

EPSDOUBLE |

2.2204460492503131E-016 |

|

IEEE Quadruple-Precision X_floating | |

|

MINQUADRUPLE |

3.36210314311209350626267781732175E-4932 |

|

MAXQUADRUPLE |

1.18973149535723176508575932662801E+4932 |

|

EPSQUADRUPLE |

9.62964972193617926527988971292464E-0035 |

For More Information:

On operators (Section 4.2, ''Operators'')

On floating lexicals (Section 11.10, ''%FLOAT, %x_FLOAT'')

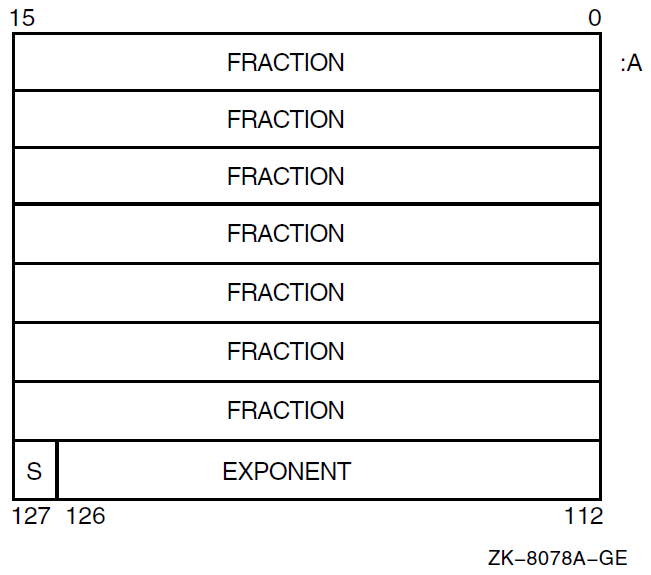

On the internal representation of real numbers (Section A.3.2, ''Representation of Floating-Point Data'')

On compilation switches (VSI Pascal User Manual)

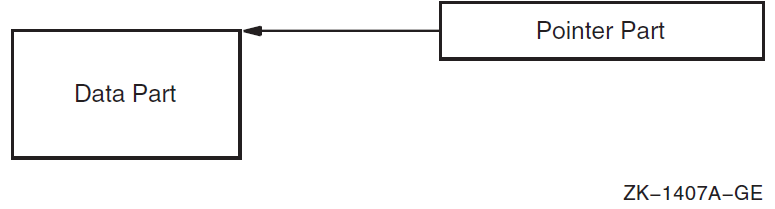

2.3. Pointer Types

A pointer type allows you to refer to a dynamic variable. Dynamic variables do not have lifetimes that are strictly related to the scope of a routine, module, or program; you can create and eliminate them at various times during program execution. Also, pointer types clearly define the type of an object, but you can create or eliminate objects during program execution.

[[attribute-list]] ^ [[attribute-list]]

base-type-identifier attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the base type.

base-type-identifier The type identifier of the dynamic variable to which the pointer refers. The base type can be any type name or schema name. (If the base type is an undiscriminated schema type, you need to supply actual discriminants when you call the NEW function.)

Unlike other variables, dynamic variables do not have identifiers. You can access them indirectly with pointers.

When you use pointers, you call the procedure NEW to allocate storage for dynamic variables. You call the procedure DISPOSE to deallocate this storage.

TYPE

My_Rec = RECORD

Name : STRING( 30 );

Age : INTEGER;

END VALUE [Name: 'Chris Lee'; Age: 29]; {Initialized}

VAR

Ptr : ^My_Rec;

{In executable section:}

NEW( Ptr );Ptr^ := My_Rec[Name: 'Kim Jones'; age: 65];

Pointers assume values through initialization, assignment, and the READ and NEW procedures. The value of a pointer is either the storage address of a dynamic variable or the predeclared identifier NIL. NIL indicates that the pointer does not currently refer to a dynamic variable.

A file referenced by a pointer is not closed until the execution of the program terminates or until the dynamic variable is deallocated with the DISPOSE procedure. If you do not want the file to remain open throughout program execution, you must use the CLOSE procedure to close it.

VAR

Ptr : ^INTEGER VALUE NIL;For performance reasons, on VSI OpenVMS I64 and VSI OpenVMS x86-64 systems, the VSI Pascal compiler assumes that all pointers point to objects that are aligned on at least octaword boundaries. The NEW predeclared routine always returns memory that is aligned on octaword boundaries.

For performance reasons on VSI OpenVMS Alpha systems, the VSI Pascal compiler assumes that all pointers point to objects that are aligned on at least quadword boundaries. The NEW predeclared routine always returns memory that is aligned on quadword boundaries.

var

p : ^ [aligned(0)] integer; { Pointer to a byte-aligned integer } var

long_ptr : ^integer;

quad_ptr : [quad] ^integer;

begin

new(long_ptr);

quad_ptr := long_ptr;

quad_ptr^ := 5;

if quad_ptr <> long_ptr then quad_ptr := long_ptr;

end;When comparing a 32-bit and a 64-bit pointer, the 32-bit pointer will be sign-extended before the comparison. Also, when assigning a 32-bit pointer value into a 64-bit pointer variable, the value will be sign-extended. You cannot assign a 64-bit pointer value into a 32-bit pointer variable.

For More Information:

On the NEW procedure (Section 8.58, ''NEW Procedure'')

On the DISPOSE procedure (Section 8.28, ''DISPOSE Procedure'')

On records (Section 2.4.2, ''RECORD Types'')

On pointers to schema types (Section 2.5, ''Schema Types'')

On linked lists (VSI Pascal User Manual)

On compiler switches for selecting alignment, packing, and allocation rules for each platform (VSI Pascal User Manual)

2.3.1. POINTER Type

To assign to or from any other type of pointer, including function result variables

To compare equality with any other type of pointer

To pass actual parameters of type POINTER to VAR and value parameters of any other type of pointer

To accept parameters of any other type of pointer with formal parameters of type POINTER

2.4. Structured Types

The structured data types are user defined and consist of components. Each component of a structured data type has its own data type; components can be any type.

To express values of structured objects (arrays, records, and sets), you can use a list of values called constructors. Constructors are valid in the TYPE, CONST, VAR, and executable sections of your program. Examples of valid constructors are provided throughout the following sections. The following sections also contain examples that show how to assign values to individual components of structured objects.

To save storage space, you can specify PACKED before any structured type identifier except VARYING OF CHAR (for example, PACKED ARRAY, PACKED RECORD, and PACKED SET). Defining PACKED structured types causes the compiler to economize storage by storing the structure in as few bits as possible. Keep in mind, however, that a packed data item is not compatible with a data item that is not packed. Also, accessing components of some packed structures can be slower than accessing components of unpacked structures.

VSI Pascal also provides the predefined structured type TIMESTAMP for more easily manipulating date and time information.

For More Information:

On string data types (Section 2.6, ''String Types'')

On VARYING OF CHAR (Section 2.6.2, ''VARYING OF CHAR Types'')

On array constructors (Section 2.4.1.2, ''ARRAY Constructors'')

On record constructors (Section 2.4.2.2, ''Record Constructors'')

On set constructors (Section 2.4.3.1, ''Set Constructors'')

On the TIMESTAMP type (Section 2.8, ''TIMESTAMP Type'')

2.4.1. ARRAY Types

An array is a group of components (called elements) that all have the same data type and share a common identifier. An individual element of an array is referred to by an ordinal index (or subscript) that designates the element's position (or order) in the array.

[[PACKED]] ARRAY [{[[attribute-list]] index-type},...] OF [[attribute-list]] component-typeattribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the component type.

index-type The type of the index, which can be any ordinal type or discriminated ordinal schema type.

component-type The type of the array components, which can be any type. The components of an array can be another array.

The indexes of an array must be of an ordinal type. However, specifying large types, such as INTEGER, as the index type can cause the memory request to exceed available memory space. To use integer values as indexes, you must specify an integer subrange in the data type definition (unless you are using a conformant-array parameter).

You can use an array component anywhere in a program that a variable of the component type is allowed. Also, the only operation defined for entire array objects is the assignment operation (:=) (unless your array components are of a FILE type).

2.4.1.1. ARRAY Components

TYPE

Count = ARRAY[1..10] OF INTEGER; {Array type of 10 integers}

VAR

Numbers : Count; {Array variable}

{In the executable section:}

Numbers[5] := 18; {Assigns the value 18 to the fifth element}VAR

Tic_Tac_Toe : ARRAY[1..3] OF ARRAY['a'..'c'] OF CHAR;

{Or equivalently:}

Tic_Tac_Toe : ARRAY[1..3, 'a'..'c'] OF CHAR; {3x3 matrix}

{In the executable section:}

Tic_Tac_Toe[ 1, 'a' ] := 'X'; {Or equivalently:}

Tic_Tac_Toe[1]['a'] := 'X';For More Information:

On character-string types (Section 2.6, ''String Types'')

On conformant-array parameters (Section 6.3.7.1, ''Conformant Array Parameters'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

On the TEXT predefined data type (Section 2.4.5, ''TEXT Type'')

2.4.1.2. ARRAY Constructors

{component }

[[data-type]] [ [[{{ {component-subrange } },... : component-value};... ]]

[[OTHERWISE component-value [[;]] ]] ]data-type component component-value OTHERWISE Specifies a value to be assigned to all array elements that have not already been assigned values.

When using array constructors, you must initialize all elements of the array; you cannot partially initialize the array.

VAR

Numbers : Count VALUE [1..3,5 : 1; 4,6 : 2; 7..9 : 3; 10 : 6];

{In the executable section, constructor type is required:}

Numbers := Count[1..3,5 : 1; 4,6 : 2; 7..9 : 3; 10 : x+3];These constructors give the first, second, third, and fifth component the value 1; the fourth and sixth component the value 2; and the seventh, eighth, and ninth components the value 3. The first constructor gives the tenth component the value 6; the second constructor, since it is in the executable section, can assign the run-time value x+3 to the tenth component.

Numbers := Count[4,6 : 2; 7..9 : 3; 10 : x+3; OTHERWISE 1];

TYPE

One_Dimension = ARRAY[1..3] OF CHAR;

Matrix = ARRAY['a'..'b'] OF One_Dimension;

VAR

Tic_Tac_Toe : Matrix;

{In the executable section:}

Tic_Tac_Toe := Matrix[ 1,3 : [OTHERWISE ' '];

2 : [ 1,3 : ' '; 2 : 'X']];For More Information:

On nonstandard array constructors (Section 2.4.6.1, ''Nonstandard Array Constructors'')

2.4.2. RECORD Types

[[PACKED]] RECORD [[field-list]] END {{{field-identifier},... : [[attribute-list]] type};... [[; variant-clause]] [[;]]}

{variant-clause [[;]]}field-identifier The name of a field.

attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the field.

type The type of the corresponding field. A field can be of any type.

variant-clause The variant part of the record.

The names of the fields must be unique within one record type, but can be repeated in different record types. You can specify the fields by specifying the record variable name (or the name of an object whose result, when used as an expression, is of a record type), followed by a period (.), and followed by the field name. If the record is unpacked, you can use a field anywhere in a program that a variable of the field type is allowed. (This manual flags circumstances in which components of packed records cannot appear where a variable of the field type is allowed.) The only operation defined for entire records is the assignment operation (:=).

TYPE

Player_Rec = RECORD

Wins : INTEGER;

Losses : INTEGER;

Percentage : REAL;

END;

VAR

Player1, Player2 : Player_Rec;

{In the executable section:}

Player1.Wins := 18; {Assigns the value 18 to the Wins field.}VAR

Player : RECORD

Wins : INTEGER VALUE 18; {Initial value for one field}

Losses : INTEGER;

Percentage : REAL;

END;TYPE

Team_Rec = RECORD

Total_Wins : INTEGER;

Total_Losses : INTEGER;

Total_Percentage : REAL;

Player1 : Player_Rec; {Defined in previous example}

Player2 : Player_Rec;

Player3 : Player_Rec;

END;

VAR

Team : Team_Rec;Team.Total_Wins := Team.Player1.Wins +

Team.Player2.Wins +

Team.Player3.Wins;For More Information:

On variant clauses (Section 2.4.2.1, ''Records with Variants'')

On record constructors (Section 2.4.2.2, ''Record Constructors'')

On specifying record fields using the WITH statement (Section 5.15, ''WITH Statement'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

2.4.2.1. Records with Variants

A record can include one or more fields or groups of fields called variants, which can contain different types or amounts of data at different times during program execution. When you use a record with variants, two variables of the same record type can represent different data. You can define a variant clause only for the last field in the record. The syntax for record variants is as follows:

{[[tag-identifier : ]] [[attribute-list]] tag-type-identifier }

CASE {discriminant-identifier } OF

{case-label-list : (field-list)};...

[[ [[;]] OTHERWISE (field-list) ]]tag-identifier The name of the tag field.

attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the variant.

tag-type-identifier The type identifier for the tag field.

discriminant-identifier TYPE

Record_Template( a : INTEGER ) = RECORD

Field_1 : REAL;

CASE a OF

0 : ( x : INTEGER );

1 : ( y : REAL );

END;case-label-list One or more case constant values of the tag field type separated by commas. A case constant is either a single constant value (for example, 1) or a range of values (for example, 5..10). You must enumerate one label for each possible value in the tag-type-identifier.

field-list The names, types, and attributes of one or more fields. At the end of a field list, you can specify another variant clause. The field list can be empty.

The tag field consists of the elements between the reserved words CASE and OF. The tag field is common to all variants in the record type. The tag field data type corresponds to the case label values and determines the current variant.

tag-identifier : [[attribute-list]]

The tag-identifier and tag-type-identifier define the name and type of the tag field. The tag-type-identifier must denote an ordinal type. You refer to the tag field in the same way that you refer to any other field in the record (with the record.field-identifier syntax).

The following example shows the use of the tag-identifier form:TYPE Orders = RECORD Part : 1..9999; CASE On_Order : BOOLEAN OF TRUE : ( Order_Quantity : INTEGER; Price : REAL ); FALSE : ( Rec_Quantity : INTEGER; Cost : REAL ); END;In this example, the last two fields in the record vary depending on whether the part is on order. Records for which the value of the tag-identifier On_Order is TRUE will contain information about the current order; those for which it is FALSE, about the previous shipment.

[[attribute-list]]

In the second form, there is no tag-identifier you can evaluate to determine the current variant. If you use this form, you must keep track of the current variant yourself. The tag-type-identifier must denote an ordinal type.

The following example shows the specification of a tag field without a tag-identifier:TYPE Characters = RECORD CASE CHAR OF 'A'..'Z' : ( Capital : INTEGER ); '0'..'9' : ( Number : INTEGER ); OTHERWISE ( Misc : BOOLEAN ); END;In this example, the last field in this record will be one of the following:The integer field Capital if the range ’A ’.. ’Z ’ is the variant most recently referred to

The integer field Number if the range ’0 ’.. ’9 ’ is the variant most recently referred to

The Boolean field Misc if the character value falls outside the previous two variants

You can refer only to the fields in the current variant. You should not change the variant while a reference exists to any field in the current variant.

You can include an OTHERWISE clause as the last case label list. OTHERWISE is equivalent to a case label list that contains tag values (if any) not previously used in the record. The variant labeled with OTHERWISE is the current variant when the tag-identifier has a value that does not occur in any of the case label lists.

VAR

Hospital : RECORD

Patient : Name;

Birthdate : Date;

Age : INTEGER;

CASE Pat_Sex : Sex OF

Male : ();

Female : ( CASE Births : BOOLEAN OF

FALSE : ();

TRUE : ( Num_Kids : INTEGER ));

END;This record includes a variant field for each woman based on whether she has children. A second variant, which contains the number of children, is defined for women who have children.

For More Information:

On the syntax of a field list (Section 2.4.2, ''RECORD Types'')

On conditions that establish a variable reference (Section 3.7, ''VAR Section'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

2.4.2.2. Record Constructors

Record constructors are lists of values that you can use to initialize a record; they have the following form:

[[data-type]] [ [[{{component},... : component-value};... ]]

[[ CASE [[tag-identifier :]] tag-value OF

[{{component},... : component-value};...] ]]

[[ OTHERWISE ZERO [[;]] ]]data-type Specifies the constructor's data type. If you use the constructor in the executable section or in the CONST section, a data-type identifier is required. Do not use a type identifier in initial-state specifiers elsewhere in the declaration section or in nested constructors.

component Specifies a field in the fixed-part of the record. Fields in the constructor do not have to appear in the same order as they do in the type definition. If you choose, you can specify fields from the variant-part as long as the fields do not overlap.

component-value Specifies a value of the same data type as the component. The value is a compile-time value; if you use the constructor in the executable section, you can also use run-time values.

CASE Provides a constructor for the variant portion of a record. If the record contains a variant, its constructor must be the last component in the constructor list.

tag-identifier Specifies the tag-identifier of the variant portion of the record. This is only required if the variant part contained a tag-identifier.

tag-value Determines which component list is applicable according to the variant portion of the record.

OTHERWISE ZERO Sets all remaining components to their binary zero value. If you use OTHERWISE ZERO, it must be the last component in the constructor.

VAR

Player1 : Player_Rec VALUE [Wins: 18; Losses: 3;

Percentage: 21/18];

{In executable section, constructor type is required

and run-time expressions are legal:}

Player1 := Player_Rec[Wins: 18; Losses: y; Percentage: y+18/18];TYPE

Team_Rec = RECORD

Total_Wins : INTEGER;

Total_Losses : INTEGER;

Total_Percentage : REAL;

Player1 : Player_Rec;

Player2 : Player_Rec;

Player3 : Player_Rec;

END;

VAR

Team : Team_Rec;

{In the executable section: }

Team :=

Team_Rec[Total_Wins: 18; Total_Losses: 3; Total_Percentage: 21/18;

Player1: [Wins: 6; Losses: 0; Percentage: 1.0 ];

Player2: [Wins: 5; Losses: 2; Percentage: 7/5 ];

Player3: [Wins: 7; Losses: 1; Percentage: 8/7 ]];VAR

Team : Team_Rec VALUE ZERO ;

Team : Team_Rec VALUE

[Total_Wins: 5; Total_Losses: 2; Total_Percentage: 7/5;

Player2: [Wins: 5; Losses: 2; Percentage: 7/5 ];

OTHERWISE ZERO

]; {Initializes Player1 and Player3}A tag-identifier and a colon (:), followed by a constant expression (if you use both a tag-identifier and a tag-type-identifier in the declaration)

A constant expression (if you use only a discriminant-identifier or a tag-type-identifier in the declaration)

TYPE

Orders = RECORD

Part : 1..9999;

CASE On_Order : BOOLEAN OF

TRUE : ( Order_Quantity : INTEGER;

Price : REAL );

FALSE : ( Rec_Quantity : INTEGER;

Cost : REAL );

END;

VAR

An_Order : Orders VALUE

[Part: 2358;

CASE On_Order : FALSE OF

[Rec_Quantity: 10; Cost: 293.99]];

{In the executable section, constructor type is required:}

An_Order := Orders

[Part: 2358;

CASE On_Order : FALSE OF [Rec_Quantity: 10; Cost: 293.99]];TYPE

Orders = RECORD

Part : 1..9999 VALUE 25;

CASE On_Order : BOOLEAN OF

TRUE : ( Order_Quantity : INTEGER VALUE 18;

Price : REAL VALUE 4.65 );

FALSE : ( Rec_Quantity : INTEGER VALUE 10;

Cost : REAL VALUE 46.50 );

END;For More Information:

On the ZERO function (Section 8.109, ''ZERO Function'')

On nonstandard record constructors (Section 2.4.6.2, ''Nonstandard Record Constructors'')

2.4.3. SET Type

A set is a collection of data items of the same ordinal type (called the base type). The SET type definition specifies the values that can be elements of a variable of that type. The SET type has the following form:

[[PACKED]] SET OF [[attribute-list]] attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the base-type.

base-type The ordinal type identifier or type definition, or discriminated schema type, from which the set elements are selected. Real numbers cannot be elements of a set type.

You define a set by listing all the values that can be its elements. A set whose base type is integer or unsigned has two restrictions. First, the set can not contain more than 256 elements. Second, the ordinal value of the elements in a set must be within the range of 0 and 255.

For sets of other ordinal base types, elements can include the full range of the type.

TYPE INTSET = SET OF 0 .. 255;

For More Information:

On the INTEGER type (Section 2.1.1.1, ''INTEGER and INTEGER64 Types'')

On the UNSIGNED type (Section 2.1.1.2, ''UNSIGNED and UNSIGNED64 Types'')

On the subrange type (Section 2.1.5, ''Subrange Types'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

On schema discriminants in sets (Section 2.5, ''Schema Types'')

2.4.3.1. Set Constructors

Set constructors are lists of values that you can use to initialize a set; they have the following form:

[[data-type]] [ [[{component-value},... ]] ] data-type The data type of the constructor. This identifier is optional when used in the CONST and executable sections; do not use this identifier in the TYPE and VAR sections or in nested constructors.

component-value Specifies values within the range of the defined data type. Component values can be subranges (..) to indicate consecutive values that appear in the set definition. These values are compile-time values; if you use the constructor in the executable section, you can also use run-time values.

A set having no elements is called an empty set and is written as empty brackets ([]).

VAR

Numbers : SET OF 35..115 VALUE [39, 67, 110..115];

{In the executable section, run-time expressions are legal:}

Numbers := [39, 67, x+95, 110..115];The set constructors contain up to nine values: 39, 67, x+95 (in the executable section only), and all the integers between 110 and 115, inclusive. If the expression x+95 evaluates to an integer outside of the range 35..115, then Pascal includes no set element for that expression.

2.4.4. FILE Type

A file is a sequence of components of the same type. The number of components is not fixed; a file can be of any length. The FILE type definition identifies the component type and has the following form:

[[PACKED]] FILE OF [[attribute-list]]

component-type attribute-list component-type Nonstatic type

Structured type with a nonstatic component

File type

Structured type with a file component

The arithmetic, relational, Boolean, and assignment operators cannot be used with file variables or structures containing file components. You cannot form constructors of file types.

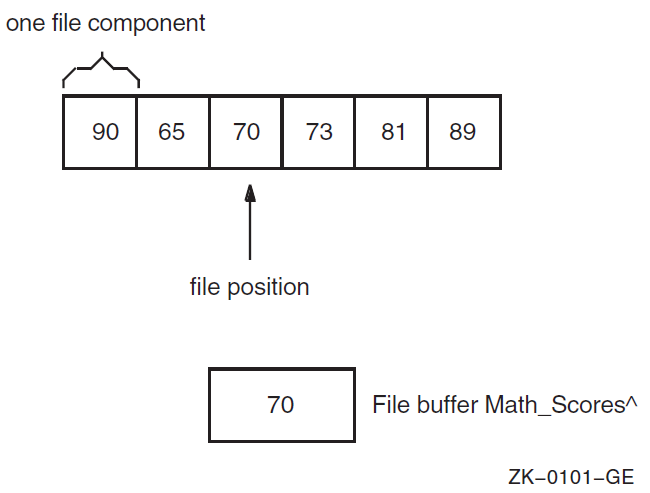

When you declare a file variable in your program, VSI Pascal automatically creates a file buffer variable of the component type. This variable takes on the value of one file component at a time.

To reference the file buffer variable, write the name of the associated file variable, followed by a circumflex (^). No operations can be performed on the file while a reference to the file buffer variable exists.

VAR

True_False_File : FILE OF BOOLEAN; {File of TRUE and FALSE values}

Experiment_Records : FILE OF RECORD {File of records}

Trial : INTEGER; {To access, Experiment_Records^.Trial}

Temp, Pressure : INTEGER;

Yield, Purity : REAL;

END;For More Information:

On file organization (Section 9.1, ''Files and File Organizations'')

On component formats (Section 9.2, ''Component Formats'')

On conditions that establish a variable reference (Section 3.7, ''VAR Section'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

2.4.5. TEXT Type

The TEXT predefined type is a file containing sequences of characters with special markers (end-of-line and end-of-file) added to the file. Although each character of a TEXT file is one file component, the end-of-line marker allows you to process the file line by line, if you choose. The TEXT type has the following form:

[[attribute-list]] TEXT attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the file components.

For More Information:

On the FILE type (Section 2.4.4, ''FILE Type'')

On TEXT files (Section 9.5, ''TEXT Files'')

On INPUT, OUTPUT, and ERR identifiers (Section 9.5, ''TEXT Files'')

2.4.6. Nonstandard Constructors

As an option, you can use another format for constructors that is provided as an VSI Pascal extension. VSI Pascal retains this format only for compatibility with programs written for use with previous versions of this product. Also, you cannot use nonstandard constructors for variables of nonstatic types.

For all nonstandard constructors, you place constant values, of the same type as the corresponding component, in a comma list within parentheses. The compiler matches the values with the components using positional syntax; you must provide a value for each component in the variable. Nested structured components are designated by another comma list inside of another set of parentheses. Nonstandard constructors are legal in the VAR and VALUE initialization sections, and in the executable section. Specifying a type identifier as part of a constructor is optional for constructors used in the VAR and VALUE initialization sections, are required for constructors in the executable section, and cannot be used for nested constructors.

For More Information:

On Pascal standards (Section 1.1, ''Pascal Language Standards'')

On standard constructors (Section 2.4, ''Structured Types'')

2.4.6.1. Nonstandard Array Constructors

The format for nonstandard array constructors is as follows:

[[data-type]] ( [[{component-value},... ]] [[ REPEAT component-value ]]

) data-type Specifies the constructor's data type. If you use the constructor in the executable section, a data-type identifier is required. Do not use a type identifier in the VAR or VALUE sections or for a nested constructor.

component-value n OF value

VAR Array1 : ARRAY[1..4] OF INTEGER; VALUE Array1 := ( 3 OF 15, 78 );

You cannot use the OF reserved word in a REPEAT clause.

REPEAT Specifies a value to be assigned to all array elements that have not already been assigned values.

TYPE

Count = ARRAY[1..10] OF INTEGER;

VAR

Numbers : Count;

VALUE

Count := ( 3 OF 1, 2, 1, 2, 3 OF 3, 3 );

{In the executable section, constructor type is required:}

Numbers := Count( 3 OF 1, 2, 1, 2, REPEAT 3 );TYPE

One_Dimension = ARRAY[1..3] OF CHAR;

Matrix = ARRAY['a'..'b'] OF One_Dimension;

VAR

Tic_Tac_Toe : Matrix;

{ In the executable section: }

Tic_Tac_Toe := Matrix( (3 OF ' '), (' ', 'X', ' '), (3 OF ' ') );For More Information:

On standard array constructors (Section 2.4.1.2, ''ARRAY Constructors'')

2.4.6.2. Nonstandard Record Constructors

The format for a nonstandard record constructor is as follows:

[[data-type]] ( [[{component-value},... ]] [[ tag-value, {component-value};... ]]

) data-type Specifies the constructor's data type. If you use the constructor in the executable section, a data-type identifier is required. Do not use a type identifier in the VAR or VALUE sections or for a nested constructor.

component-value Specifies a compile-time value of the same data type as the component. The compiler assigns the first value to the first record component, the second value to the second record component, and so forth.

tag-value Specifies a value for the tag-identifier of a variant record component. The value that you specify as this component of the constructor determines the types and positions of the remaining component values (according to the variant portion of the type definition).

TYPE

Player_Rec = RECORD

Wins : INTEGER;

Losses : INTEGER;

Percentage : REAL;

VAR

Player1 : Player_Rec := ( 18, 6, 24/18 );

{In the executable section, constructor type is required:}

Player1 := Player_Rec( 18, 6, 24/18 );TYPE

Team_Rec = RECORD

Total_Wins : INTEGER;

Total_Losses : INTEGER;

Total_Percentage : REAL;

Player1 : Player_Rec;

Player2 : Player_Rec;

Player3 : Player_Rec;

END;

VAR

Team : Team_Rec;

{In the executable section: }

Team := Team_Rec ( 18, 3, 18/21,

( 6, 0, 1.0 ),

( 5, 2, 5/7 ),

( 7, 1, 7/8 ) );TYPE

Orders = RECORD

Part : 1..9999;

CASE On_Order : BOOLEAN OF

TRUE : ( Order_Quantity : INTEGER;

Price : REAL );

FALSE : ( Rec_Quantity : INTEGER;

Cost : REAL );

END;

VAR

An_order : Orders := ( 2358, FALSE, 10, 293.99 );For More Information:

On standard record constructors (Section 2.4.2.2, ''Record Constructors'')

On record variants (Section 2.4.2.1, ''Records with Variants'')

2.5. Schema Types

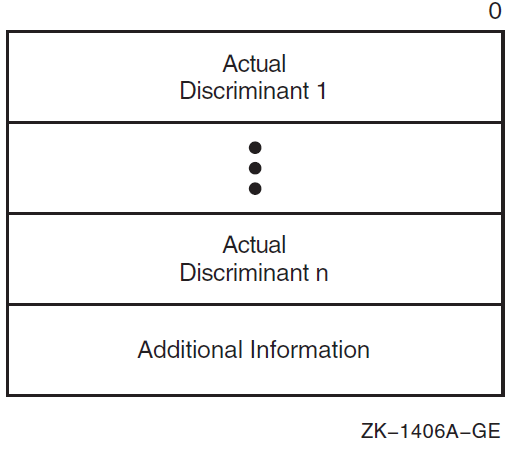

A schema type is a user-defined construct that provides a template for a family of distinct data types. A schema type definition contains one or more formal discriminants that take the place of specific boundary values or variant-record selectors. By specifying boundary or selector values to a schema type, you form a valid data type; the provided boundary or selector values are called actual discriminants. Schema types have the following form:

schema-identifier ({{discriminant-identifier},... :

[[attribute-list]] ordinal-type-name};... )

= [[attribute-list]] type-denoter;schema-identifier The name of the schema.

discriminant-identifier The name of a formal discriminant.

attribute-list One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the type-denoter.

ordinal-type-name The type of the formal discriminant, which must be an ordinal type (except those types that have INTEGER64 or UNSIGNED64 base types).

type-denoter The type definition of the components of the schema. This must define a new record, array, set, or subrange type.

TYPE

Array_Template( Upper_Bound : INTEGER )

= ARRAY[1..Upper_Bound] OF INTEGER;As the domain type of a pointer

As the type of a formal parameter

TYPE

Vector( d : INTEGER ) = ARRAY[0..d-1] OF BOOLEAN;

Number_Line( Starting, Distance : INTEGER ) =

Starting..Starting+Distance;

My_Subrange( l,u : INTEGER ) = l..u;

Shift_Array_Index( l2, u2, Length : INTEGER ) =

ARRAY[My_Subrange( l2+10, u2+10 )] OF STRING( Length );TYPE

Array_Template( Upper_Bound : INTEGER )

= ARRAY[1..Upper_Bound] OF INTEGER;

VAR

Array1 : Array_Template( 10 ); {ARRAY[1..10] OF INTEGER;}

Array2 : Array_Template( x ); {Upper boundary determined at

run time by variable or

function call}In the previous example, the actual discriminants 10 and x complete the boundaries for Array_Template, forming two complete data types within the same schema type family. A schema type that has been provided actual discriminants is called a discriminated schema; discriminated schema can appear in either the TYPE or VAR sections. The type specifiers Array_Template( 10 ) and Array_Template( x ) are examples of discriminated schema.

Actual discriminants can be compile- or run-time expressions. This expression must be assignment compatible with the ordinal type specified for the formal discriminant. Also, the actual discriminant value must be inside the range specified for the formal discriminant; in the case of subranges, the upper value must be greater than or equal to the lower value. In the previous example, 10 and x must be within the range -MAXINT..MAXINT.

TYPE

Array_Type1 = Array_Template( 10 );

PROCEDURE Example( Param : Array_Type1 ); {Procedure body...}TYPE My_Subrange( a, b : INTEGER ) = a..b; Sub_A = My_Subrange( 1, 5 ); Sub_B = My_Subrange( 1, 5 ); Sub_C = My_Subrange( -50, 50 );

TYPE

My_Subrange( a, b : INTEGER ) = a..b;

My_Array( Upper : INTEGER ) = ARRAY[1..Upper] OF INTEGER;

VAR

i : My_Array( 10 );

j : My_Array( 10 );

k : My_Array( 15 );

l : ARRAY[ My_Subrange( 1, 10 ) ] OF INTEGER;

m : ARRAY[ My_Subrange( 1, 10 ) ] OF INTEGER;

{In the executable section:}

i := j; {Legal; same schema family, same actual discriminant}

i := k; {Illegal; same schema family, different actual}

i := l; {Illegal; different types}

l := m; {Illegal; different types}Types l and m are not assignment compatible despite having the same subrange values specified by the same schema type; the two distinct type declarations create two distinct types, regardless of the ranges of the two types.

VAR

Array1 : Array_Template( 10 );

{In the executable section:}

WRITELN( Array1.Upper_Bound ); {Writes 10 to the default device}FOR i := 1 TO Array1.Upper_Bound DO Array1[i] := i;

You can use discriminated schema in the type-denoter of a schema definition. You can also discriminate a schema in the type-denoter of a schema definition, but the actual discriminants must be expressions whose values are nonvarying; the actual discriminants cannot be variables or function calls.

TYPE

{ Legal schema types: }

Range1( a, b : INTEGER ) = SET OF a..b+1; {Run-time bounds checking}

My_Record( Number_Size, Status_Size : INTEGER ) = RECORD

Part_Number : PACKED ARRAY[1..Number_Size] OF INTEGER;

Status : STRING( Status_Size ); {Nested schema}

END;

Range2( Low, Span : INTEGER ) = Low..Low + Span;

My_Integer( Dummy : INTEGER ) = -MAXINT-1..MAXINT;

Matrix( Bound : INTEGER ) = ARRAY[1..Bound, 1..Bound] OF REAL;

{ Illegal schema types (they do not form "new" types): }

My_String( Len : INTEGER ) = VARYING[Len] OF CHAR;

My_Integer( Dummy : INTEGER ) = INTEGER;2.6. String Types

CHAR type

PACKED ARRAY OF CHAR user-defined types

VARYING OF CHAR user-defined types

STRING predefined schema

Objects of the CHAR data type are character strings with a length of 1 and are lowest in the order of character string complexity. You can assign CHAR data to variables of the other string types.

The PACKED ARRAY OF CHAR types allow you to specify fixed-length character strings. The VARYING OF CHAR types are a VSI Pascal extension that allows you to specify varying-length character strings with a constant maximum length. The STRING types provide a standard way for you to specify storage for varying-length character strings with a maximum length that can be specified at run time.

To provide values for variables of these types, you should use a character-string constant (or an expression that evaluates to a character string) instead of an array constructor. Using array constructors with STRING and VARYING OF CHAR types generates an error; to use array constructors with PACKED ARRAY OF CHAR types, you must specify component values for every element in the array (otherwise, you generate an error).

VAR String1 : VARYING[10] OF CHAR

Generally, you can use any member of the ASCII character set in character-string constants and expressions. However, some members of the ASCII character set, including the bell, the backspace, and the carriage return, are nonprinting characters. The extended string format for character strings with nonprinting characters is as follows:

{'printing-string'({ordinal-value},...)}...

printing-string

A character-string constant.

Two bells'(7,7)' in a null-terminated ASCII string.'(0)

string-access "[" lower-bound ".." upper-bound "]"

var s : packed array [1..10] of char; s[1..5] :='hello'; s[6..10] := 'world';

procedure do_buf(var p : packed array [1..u:integer] of char);

begin p := '12345'; end;

var buff : packed array [1..10] of char;

do_buff(buff[1..5]);

do_buff(buff[6..10);

writeln(buff);To avoid compile-time warning messages about passing components of PACKED structures to VAR parameters, use /USAGE=NOPACKED_ACTUALS to compile.

In expressions, substring access behaves much like the SUBSTR built-in.

VSI Pascal also provides features for handling null-terminated strings. These are useful for communicating with routines written in the C language.

For More Information:

On the CHAR data type (Section 2.1.2, ''CHAR Type'')

On the ASCII character set (Section 1.2.1, ''Character Set'')

On null-terminated strings (Section 2.7, ''Null-Terminated Strings'')

2.6.1. PACKED ARRAY OF CHAR Types

User-defined packed arrays of characters with specific lower and upper bounds provide a method of specifying fixed-length character strings. The string's lower bound must equal 1. The upper bound establishes the fixed length of the string.

VAR My_String : PACKED ARRAY[1..20] OF CHAR;

Note

If the upper bound of the array exceeds 65,535, if the PACKED reserved word is not used, or if the array's components are not byte-sized characters, the compiler does not treat the array as a character string.

VAR

States : PACKED ARRAY[1..20] OF CHAR

VALUE 'Hello'; {Is legal}

States : PACKED ARRAY[1..20] OF CHAR

VALUE [1:'H';2:'e';3:'l';4:'l';5:'o'] {Generates

an error}

States : PACKED ARRAY[1..20] OF CHAR

VALUE [1:'H';2:'e';3:'l';4:'l';5:'o';

OTHERWISE ' '] {Is legal,

but awkward}For More Information:

On arrays (Section 2.4.1, ''ARRAY Types'')

2.6.2. VARYING OF CHAR Types

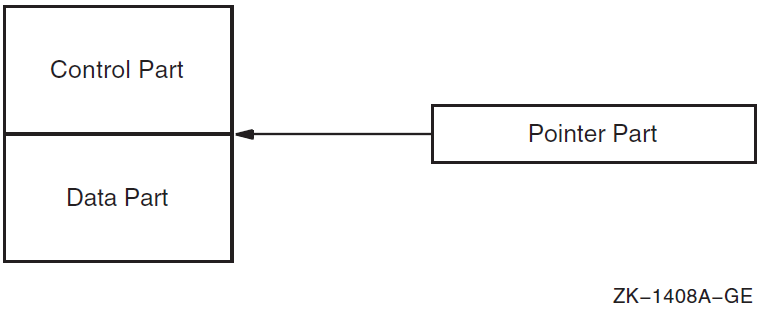

The VARYING OF CHAR user-defined types are an VSI Pascal extension that provides a way of declaring variable-length character strings with a constant maximum length. If you require portable code, use the STRING predefined schema types to specify variable-length character strings.

VARYING OF CHAR types have the following form:

VARYING [upper-bound] OF [[attribute-list]] CHAR upper-bound An unsigned integer in the range from 1 through 65,535 that indicates the length of the longest possible string.

attribute-list

One or more identifiers that provide additional information about the VARYING OF CHAR string component.

VAR String1 : VARYING[10] OF CHAR VALUE '';

RECORD

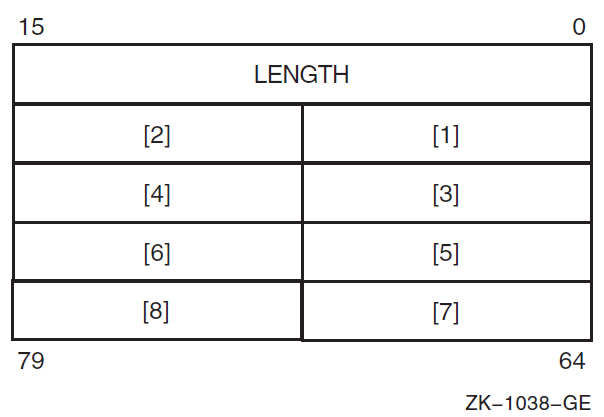

LENGTH : [WORD] 0..upper-bound; {Length of current string}

BODY : PACKED ARRAY[1..upper-bound] OF CHAR; {Current string}

END;VAR

String1 : VARYING[10] OF CHAR VALUE 'Wolf';

{In the executable section: }

Max_Length := SIZE( string1.BODY );

WRITELN( Max_Length ); {writes '10'}To determine the current length of a VARYING OF CHAR variable, use the LENGTH predeclared function. From the previous example, the result of LENGTH( String1 ) is the same as String1.LENGTH.

String1[8] := 'L';

You cannot specify an index value that is greater than the length of the current string. VSI Pascal does not pad remaining characters in the current string with blanks ( ’ ’). If you specify an index that is greater than the current length of the string, an error occurs.

For More Information:

On arrays (Section 2.4.1, ''ARRAY Types'')

On attributes (Chapter 10, "Attributes")

On the SIZE predeclared function (Section 8.81, ''SIZE Function'')

On the LENGTH predeclared function (Section 8.49, ''LENGTH Function'')

2.6.3. STRING Schema Type

TYPE STRING( capacity : INTEGER ) = VARYING[capacity] OF CHAR;

STRING( capacity ) An unsigned integer in the range 1..65,535 that indicates the length of the longest possible string.

VAR

Short_String : STRING( 5 ); {Maximum length of 5 characters}

Long_String : STRING( 100 ); {Maximum length of 100 characters}VAR Short_String : STRING( 5 ) VALUE '';

VAR

String1 : STRING( 10 ) VALUE 'Wolf';

{In the executable section: }

WRITELN( String1.CAPACITY ); {prints '10'}

WRITELN(

String1.LENGTH

{prints '4'}The value String1.BODY contains the four-character string 'Wolf' followed by whatever is currently stored in memory for the remaining six characters.

To determine the current length of a STRING variable, you can use the LENGTH predeclared function. The result of LENGTH( String1) is the same as String1.LENGTH.

String1[5] := 't';

VAR

String1 : STRING( 10 ) VALUE 'Wombat';

x : CHAR;

{In the executable section:}

x := String1[9]; {Generates an error}

x := String1.BODY[9]; {Provides whatever is in memory there}

x := String1[5]; {Is legal}

String1[9] := 'X'; {Generates an error}For More Information:

On schema types (Section 2.5, ''Schema Types'')

On arrays (Section 2.4.1, ''ARRAY Types'')

On the SIZE predeclared function (Section 8.81, ''SIZE Function'')

2.7. Null-Terminated Strings

VSI Pascal includes routines and a built-in type to better coexist with null-terminated strings in the C language.

C_STR_T = ^ ARRAY [0..0] OF CHAR;