VSI OpenVMS User's Manual

- Operating System and Version:

- VSI OpenVMS x86-64 Version 9.2-1 or higher

VSI OpenVMS IA-64 Version 8.4-1H1 or higher

VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 or higher

Preface

1. About VSI

VMS Software, Inc. (VSI) is an independent software company licensed by Hewlett Packard Enterprise to develop and support the OpenVMS operating system.

2. Intended Audience

This manual is intended for all users of the VSI OpenVMS operating system.

A system manager performs the administrative tasks that create and maintain an efficient computing environment. If you are a system manager or want to understand system management concepts and procedures, refer to the VSI OpenVMS System Manager's Manual.

3. Document Structure

Each chapter describes concepts and procedures for performing computing tasks. Basic information is presented first within each chapter; more complex concepts and procedures are presented last.

3.1. Getting Started

Chapter 1, "Getting Started with the OpenVMS Operating System" describes how to log in and log out of the system, how to change your password, and how to get help.

Chapter 2, "Using DCL to Interact with the System" describes how to use the DIGITAL Command Language (DCL).

Chapter 3, "Storing Information with Files" describes files and how you can use them to store information. It also includes examples for creating, copying, renaming, displaying, deleting, protecting, and printing files.

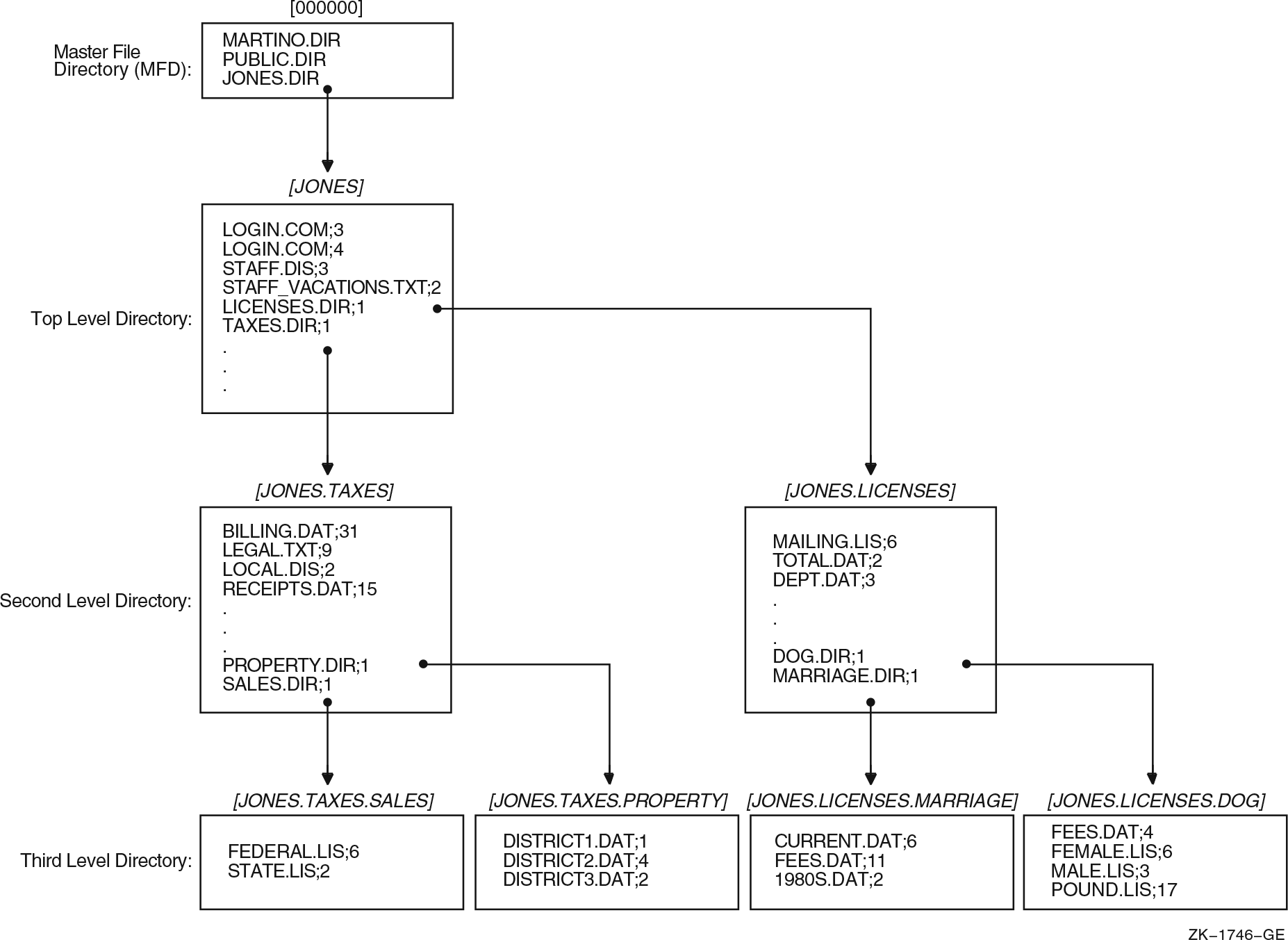

Chapter 4, "Organizing Files with Directories" describes how to use directories to organize and manage files.

Chapter 5, "Extended File Specifications" describes the extended file specifications environment for OpenVMS Alpha systems using ODS-5.

Chapter 6, "Using Disk and Tape Drives" describes how to reserve tapes or disks for private use. Unlike devices that are shared by a group of users, private devices might not be set up and maintained by a system manager.

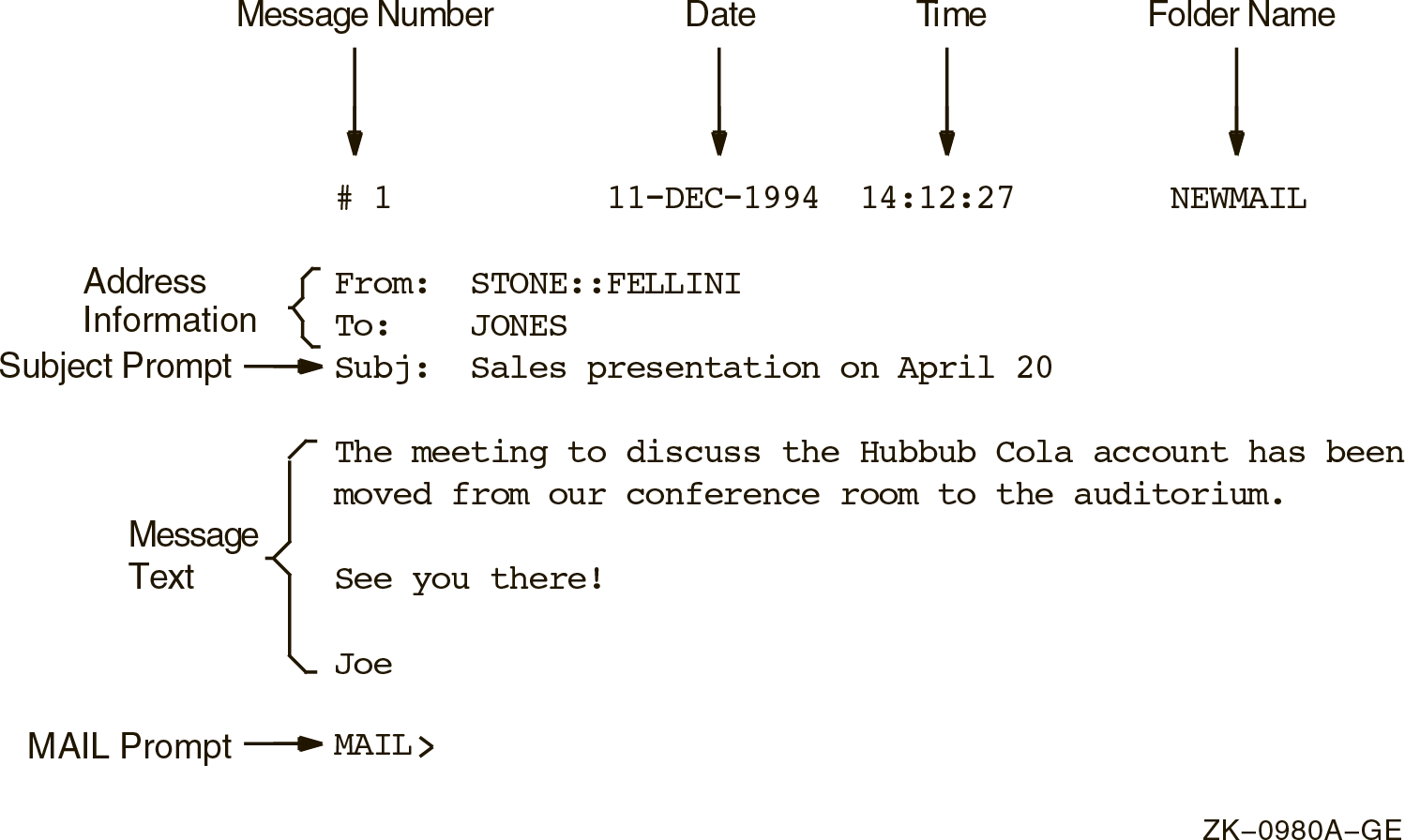

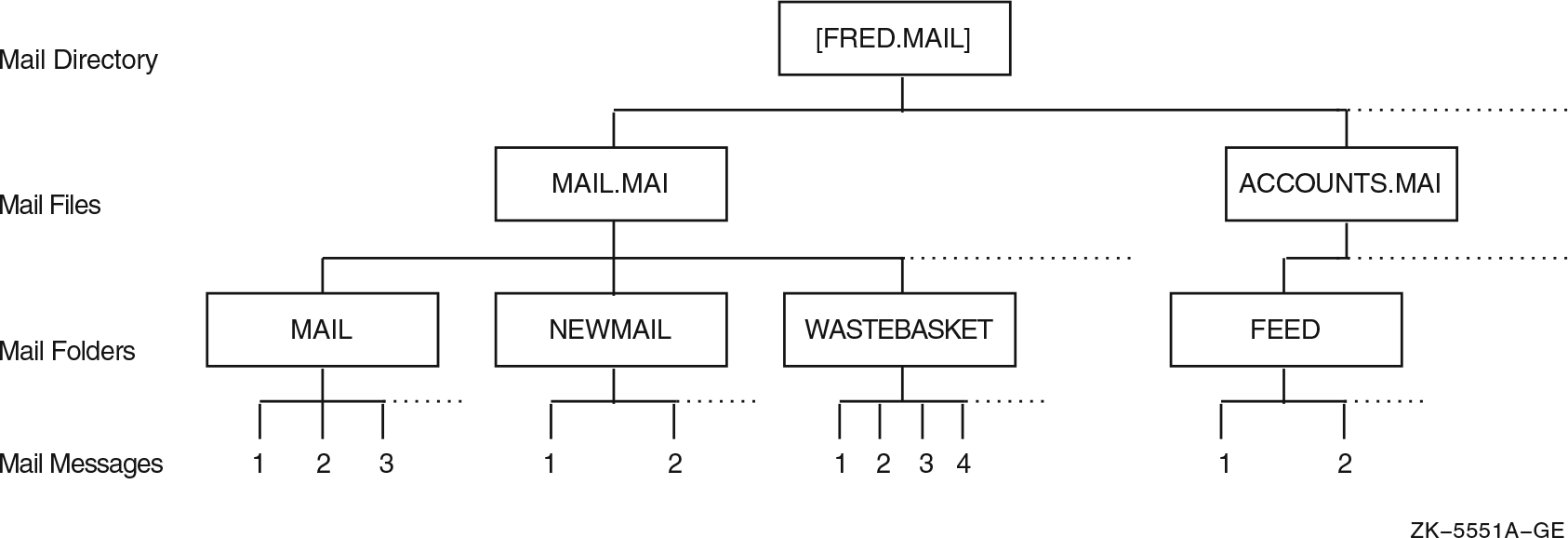

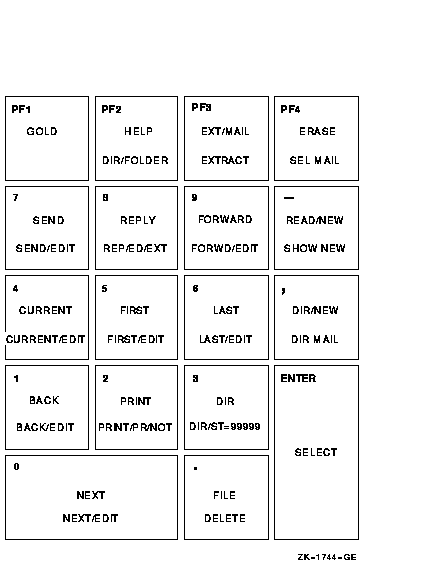

Chapter 7, "Using Mail to Communicate with Others" describes how to use the Mail utility (MAIL) to communicate with other users on your system or on any other computer that is connected to your system with the DECnet for OpenVMS network. The chapter includes a sample mail message; step-by-step instructions for reading, sending, replying to, forwarding, and organizing mail messages; a summary of Mail commands; and instructions on how to use the MIME utility.

3.2. Manipulating Text and Records

Chapter 8, "Editing Text Files with EVE" describes EVE, an interactive text editor that is included with the OpenVMS operating system. The chapter describes how to use EVE to create and edit new files or to edit existing files. It includes summaries of EVE commands.

Chapter 9, "Sorting and Merging Files" describes how to use the Sort/Merge utility (SORT/MERGE) to sort records from one or more input files or to merge files that have been sorted. The chapter includes a summary of Sort/Merge command qualifiers.

3.3. Ensuring Security

Chapter 10, "Controlling Access to Resources" describes general security issues such as controlling access to protected objects and accessing data on remote systems.

3.4. Logical Names and Symbols

Chapter 11, "Defining Logical Names for Devices and Files" describes how to create and use logical names to represent files, directories, and devices. The chapter also summarizes the logical names created by the system.

Chapter 12, "Defining Symbols, Commands, and Expressions" describes how to use symbols to represent commands, character strings, and numeric data. The chapter also describes how to combine symbols into expressions to manipulate the values that the symbols represent.

3.5. Programming

Chapter 13, "Introduction to Command Procedures" describes basic techniques used in writing command procedures, which are files that contain DCL commands and data lines used by DCL commands.

Chapter 14, "Advanced Programming with DCL" describes advanced techniques used in writing command procedures. This chapter also describes how to use the PIPE command interactively and within command procedures.

Chapter 15, "Using Lexical Functions to Obtain and Manipulate Information" describes how to use lexical functions within a command procedure to get information about your process or the system environment.

3.6. Managing Processes

Chapter 16, "Understanding Processes and Batch Jobs" describes processes, which are environments created by the OpenVMS operating system that let you interact with the system. The chapter describes how and when to use subprocesses, programs, and batch jobs.

3.7. Reference Sections

Appendix A, "Character Sets" describes the DEC Multinational character set and the DCL character set.

Appendix B, "Annotated Command Procedures" contains complete command procedures that demonstrate the concepts and techniques discussed in Chapters 13, 14, and 15.

4. VSI Encourages Your Comments

You may send comments or suggestions regarding this manual or any VSI document by sending electronic mail to the following Internet address: <docinfo@vmssoftware.com>. Users who have VSI OpenVMS support contracts through VSI can contact <support@vmssoftware.com> for help with this product.

5. OpenVMS Documentation

The full VSI OpenVMS documentation set can be found on the VMS Software Documentation webpage at https://docs.vmssoftware.com.

6. Conventions

The following conventions are used in this manual:

| Convention | Meaning |

|---|---|

Ctrl/X | A sequence such as

Ctrl/x

indicates that you must hold down the key labeled Ctrl while you

press another key (x) or

a pointing device button. |

PF1

X | A sequence such as PF1

X indicates that you

must first press and release the key labeled PF1 and then press and

release another key (x)

or a pointing device button. |

| Enter | In examples, a key name in bold indicates that you press that key. |

… |

A horizontal ellipsis in examples indicates one of the

following possibilities:

|

. . . | A vertical ellipsis indicates the omission of items from a code example or command format; the items are omitted because they are not important to the topic being discussed. |

| ( ) |

In command format descriptions, parentheses indicate that you must enclose choices in parentheses if you specify more than one. In installation or upgrade examples, parentheses indicate the possible answers to a prompt, such as:

|

| [ ] |

In command format descriptions, brackets indicate optional choices. You can choose one or more items or no items. Do not type the brackets on the command line. However, you must include the brackets in the syntax for directory specifications and for a substring specification in an assignment statement. In installation or upgrade examples, brackets indicate the default answer to a prompt if you press Enter without entering a value, as in:

|

| | | In command format descriptions, vertical bars separate choices within brackets or braces. Within brackets, the choices are optional; within braces, at least one choice is required. Do not type the vertical bars on the command line. |

| { } | In command format descriptions, braces indicate required choices; you must choose at least one of the items listed. Do not type the braces on the command line. |

| bold type | Bold type represents the name of an argument, an attribute, or a reason. In command and script examples, bold indicates user input. Bold type also represents the introduction of a new term. |

| italic type | Italic type indicates important information, complete titles of manuals, or variables. Variables include information that varies in system output (Internal error number), in command lines (/PRODUCER=name), and in command parameters in text (where dd represents the predefined code for the device type). |

| UPPERCASE TYPE | Uppercase type indicates a command, the name of a routine, the name of a file, or the abbreviation for a system privilege. |

Example |

This typeface indicates code examples, command examples, and interactive screen displays. In text, this type also identifies website addresses, UNIX command and pathnames, PC-based commands and folders, and certain elements of the C programming language. |

| - | A hyphen at the end of a command format description, command line, or code line indicates that the command or statement continues on the following line. |

| numbers | All numbers in text are assumed to be decimal unless otherwise noted. Nondecimal radixes-binary, octal, or hexadecimal-are explicitly indicated. |

Chapter 1. Getting Started with the OpenVMS Operating System

Logging in

Logging in from a PC

Choosing passwords for your account

Reading informational messages

Types of logins and login classes

Login failures

Changing passwords

Password and account expiration times

Guidelines for protecting your password

Recognizing system responses

Getting help about the system

Logging out of the system

Logging out without compromising system security

Networks

For complete descriptions of all commands referenced in this chapter, refer to the VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary and online help.

1.1. Logging In

Logging in consists of gaining access to the system and identifying yourself as an authorized user. When you log in, the system creates an environment from which you can enter commands. This environment is called your process.

The way you log in and out of the OpenVMS operating system depends on how the system is set up at your site. This section provides a general description of logging in to and out of the operating system. Check with your system manager for the procedures specific to your site.

To interact with the operating system, you must log in to a user account. An account is a name or number that identifies you to the system when you log in. That name or number tells the system where your files are stored and the type of access you have to other files.

Your system manager (or whoever authorizes system use at your installation) usually sets up accounts and grants privileges according to your needs. The type of access rights and privileges enabled for your account determine whether you have access to files, images, or utilities that might affect system performance or other users.

To access your account, you need to enter your user name and password. Your system manager usually provides you with your user name and initial password. Your user name identifies you to the system and distinguishes you from other users. Your password is for your protection. If you maintain its secrecy, other users cannot use system resources under your user name.

|

Step |

Task |

|---|---|

|

1 |

The system displays a prompt for your user

name:

Username: Type your user name and press Enter. You have approximately 30 seconds to do this; otherwise, the system "times out." If a timeout occurs, you must start the login procedure again. The system displays your user name on the screen as you type it. For example:

Username: CASEY

The system prompts you for your password:

Password:

)

|

|

2 |

Type your password and press Enter. The system does not display your password, which is sometimes referred to as "no echo." |

|

3 |

Depending on how your system manager has set up your account, you might be required to enter a second password or use an automatically generated password (see Section 1.3.4, ''Types of Passwords''). |

1.1.1. Successful Logins

If your login is successful, the system displays a dollar sign ($) in the left margin of your screen. The dollar sign is the default DCL prompt; it indicates that the system is ready to use.

Username: CASEY

Password:

Welcome to OpenVMS on node MARS

Last interactive login on Friday, 11-DEC-2002 08:41

Last non-interactive login on Thursday, 10-DEC-2002 11:05

$1.1.2. Login Errors

User authorization failureand you are not logged in. If you make a mistake, press Enter and try again. If your password has expired, you need to change your password; the system will automatically display the Set Password: prompt. See Section 1.7, ''Changing Passwords'' for information on changing your password in this instance. If you have any other problems logging in, get help from the person who set up your account.

1.2. Logging In From a PC

In previous times, you would connect to a host computer with a video terminal that consisted of a monitor and a keyboard. All computing power resided on the host computer running the OpenVMS operating system, often located in a central computing room. Today it is more common to work from a personal computer (PC) or workstation that has its own set of independent computing capabilities. In this situation you connect to a host computer running OpenVMS via a terminal emulation program.

A terminal emulation program lets you connect to an OpenVMS system over a TCP/IP network, the Internet, or an intranet. Your interactions with the operating system display on the PC monitor using the interface provided by the terminal emulation program. To connect to OpenVMS in this way, start the terminal emulation program, select the system you want to connect to, and then log in to the OpenVMS operating system as described in this chapter.

1.3. Choosing Passwords for Your Account

Include both numbers and letters in the password. Although a 6-character password that contains only letters is fairly secure, a 6-character password with both letters and numbers is much more secure.

Choose passwords that contain 6 to 10 characters. Adequate length makes passwords more secure. You can choose a password as long as 32 characters.

Do not select passwords from a dictionary or from your native language.

Avoid choosing words readily associated with your computer site or yourself, such as the name of a product or the model of your car.

Choose new passwords each time. Do not reuse old ones.

Your system manager or security administrator may set up additional restrictions, for example, not allowing passwords with fewer than 10 characters or not allowing repeats of passwords.

|

Secure Passwords |

High-Risk Passwords |

|---|---|

|

Nonsense syllables: aladaskgam eojfuvcue joxtyois |

Words with a strong personal association: your name, the name of a loved one, the name of your pet, the name of your town, the name of your automobile, etc. |

|

A mixed string: 492_weid $924spa zu_$rags |

A work-related term: your company name a special project your work group name |

1.3.1. Obtaining Your Initial Password

Typically, when you learn that an account has been created for you on the system, you are told whether a user password is required. If user passwords are in effect, your system manager will usually assign a specific password for your first login. This password has been placed in the system user authorization file (UAF) with other information about how your account can be used.

It is inadvisable to have passwords that others could easily guess. Ask the person creating the account for you to specify a password that is difficult to guess. If you have no control over the password you are given, you might be given a password that is the same as your first name. If so, change it immediately after you log in. The use of first or last names as passwords is a practice so well known that it is undesirable from a security standpoint.

At the time your account is created, you should also be told a minimum length for your password and whether you can choose your new password or whether the system generates the password for you.

1.3.2. Changing Your Initial Password

Log in to your account soon after it is created to change your password. If there is a time lapse from the moment your account is created until your first login, other users might log in to your account successfully, gaining a chance to damage the system. Similarly, if you neglect to change the password or are unable to do so, the system remains vulnerable. Possible damage depends largely on what other security measures are in effect. See Section 1.7, ''Changing Passwords'' for more information on changing passwords.

1.3.3. Restrictions on Passwords

It automatically compares new passwords to a system dictionary. This helps to ensure that a password is not a native language word.

It maintains a history list of your old passwords and compares each new password to this list to be sure that you do not reuse a password.

It enforces a minimum password length, which the system manager specifies in your UAF record.

The system rejects any passwords that it finds in a system dictionary, that you have used before, and that are shorter than the minimum password length specified in your UAF.

1.3.4. Types of Passwords

User password

Required for most accounts. After entering your user name, you are prompted for a password. If the account requires both primary and secondary passwords, two passwords must be entered.

System password

Controls access to particular terminals and is required at the discretion of the security administrator. System passwords are usually necessary to control access to terminals that might be targets for unauthorized use, such as dialup and public terminal lines.

Primary password

The first of two passwords to be entered for an account requiring both primary and secondary passwords.

Secondary password

The second of two passwords to be entered for an account requiring both primary and secondary passwords. The secondary password provides an additional level of security on user accounts. Typically, the primary user does not know the secondary password; a supervisor or other key person must be present to supply it. For certain applications, the supervisor may also decide to remain present while the account is in use. Thus, secondary passwords facilitate controlled logins and the actions taken after a login.

Secondary passwords can be time-consuming and inconvenient. They are justified only at sites with maximum security requirements. An example of an account that justifies dual passwords would be one that bypasses normal access controls to permit emergency repair to a database.

1.3.5. Entering a System Password

Your security administrator will tell you if you must specify a system password to log in to one or more of the terminals designated for your use. Ask your security administrator for the current system password, how often it changes, and how to obtain the new system password when it does change.

| Step |

Task |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Press the Enter key until the terminal responds with the recognition character, which is commonly a bell. |

| 2 |

Type the system password and press Enter. There is no prompt and the system does not display the characters you type. If you fail to specify the correct system password, the system does not notify you. Initially, you might think the system is malfunctioning unless you know that a system password is required at that terminal. If you do not receive a response from the system, assume that you have entered the wrong password and try again. |

| 3 |

When you enter the correct system password, you receive the system

announcement message, if there is one, followed by the Username: prompt. For

example:

MAPLE - A member of the Forest Cluster

Unauthorized Access is Prohibited

Username: |

1.3.6. Entering a Secondary Password

Your security administrator decides whether to require the use of secondary passwords for your account at the time your account is created. When your account requires primary and secondary passwords, you need two passwords to log in. Minimum password length, which the security administrator specifies in your UAF, applies to both passwords.

As with a single password login, the system allots a limited amount of time for the entire login. If you do not enter a secondary password in time, the login period expires.

WILLOW - A member of the Forest Cluster

Welcome to OpenVMS on node WILLOW

Username: RWOODS

Password: Enter

Password: Enter

Last interactive login on Friday, 11-DEC-2002 10:22

$1.3.7. Password Requirements for Different Types of Accounts

Accounts secured with passwords that you or the security administrator change periodically. This account type is the most common.

Accounts that always require passwords but prohibit you from changing the password. By locking the password (setting the LOCKPWD flag in the UAF), the security administrator controls all changes made to the password.

Restricted accounts limit your use of the system and sometimes require a password.

Open accounts require no password. When you log in to an open account, the system does not prompt you for a password and you do not need to enter one. You can begin entering commands immediately. Because open accounts allow anyone to gain access to the system, they are used only at sites with minimal security requirements.

1.4. Reading Informational Messages

When you log in from a terminal that is directly connected to a computer, the OpenVMS system displays informational system messages, as shown in the following example.

WILLOW - A member of the Forest ClusterUnlawful Access is Prohibited Username: RWOODS Password: You have the following disconnected process:

Terminal Process name Image name VT320: RWOODS (none) Connect to above listed process [YES]: NO Welcome to OpenVMS on node WILLOW

Last interactive login on Wednesday, 11-DEC-2002 10:20

Last non-interactive login on Monday, 30-NOV-2002 17:39

2 failures since last successful login

You have 1 new mail message.

$

The announcement message identifies the node (and, if relevant, the OpenVMS Cluster name). It may also warn unauthorized users that unlawful access is prohibited. The system manager or security administrator can control both the appearance and the content of this message. | |

A disconnected process message informs you that your process was disconnected at some time after your last successful login but is still available. You have the option of reconnecting to the old process, in the state it was in before you were disconnected. The system displays the disconnected message only when the following conditions exist:

In general, the security administrator should allow you to reconnect because this ability poses no special problems for system security. However, the security administrator can disable this function by changing the setup on terminals and by disabling virtual terminals on the system. For information on setting up and reconnecting to virtual terminals, refer to the VSI OpenVMS System Manager's Manual. | |

A welcome message indicates the version number of the OpenVMS operating system that is running and the name of the node on which you are logged in. The system manager can choose a different message or can suppress the message entirely. | |

The last successful interactive login message provides the time of the last completed login for a local, dialup, or remote login. The system does not count logins from a subprocess whose parent was one of these types. | |

The last successful noninteractive login message provides the time the last noninteractive (batch or network) login completed. | |

The number of login failure messages indicates the number of failed attempts at login. An incorrect password is the only source of login failure that is counted. To attract your attention, a bell rings after the message appears. | |

The new mail message indicates if you have any unread mail messages. |

1.4.1. Suppressing Messages

A security administrator can suppress the announcement and welcome messages, which include node names and operating system identification. Because login procedures differ according to operating system, it is more difficult to log in without this information.

The last login success and failure messages are optional. Your security administrator can enable or disable them as a group. Sites with medium-level or high-level security needs display these messages because they can indicate break-in attempts. In addition, by showing that the system is monitoring logins, these messages can be a deterrent to potential illegal users.

1.4.2. Successful Login Messages

Each time you log in, the system resets the values for the last successful login and the number of login failures. If you access your account interactively and do not specify an incorrect password in your login attempts, you may not see the last successful noninteractive login and login failure messages.

1.5. Types of Logins and Login Classes

Logins can be either interactive or noninteractive. When you log in interactively, you enter a user name and a password. In noninteractive logins, the system performs the identification and authentication for you; you are not prompted for a user name and password.

In addition to interactive and noninteractive logins, the OpenVMS operating system recognizes different classes of logins. How you log in to the system determines the login class to which you belong. Based on your login class, as well as the time of day or day of the week, the system manager controls your access to the system.

1.5.1. Interactive Logins

Local

You log in from a terminal connected directly to the central processor or from a terminal server that communicates directly with the central processor.

Dialup

You log in to a terminal that uses a modem and a telephone line to make a connection to the computer system. Depending on the terminal that your system uses, you might need to execute a few additional steps initially. Your site security administrator can give you the necessary details.

Remote

You log in to a node over the network by entering the DCL command SET HOST. For example, to access the remote node HUBBUB, you enter the following command:$ SET HOST HUBBUB

If you have access to an account on node HUBBUB, you can log in to that account from your local node. You have access to the facilities on node HUBBUB, but you remain physically connected to your local node.

For additional information on remote sessions, see Section 1.12.2, ''Ending a Remote Session''.

1.5.2. Noninteractive Logins

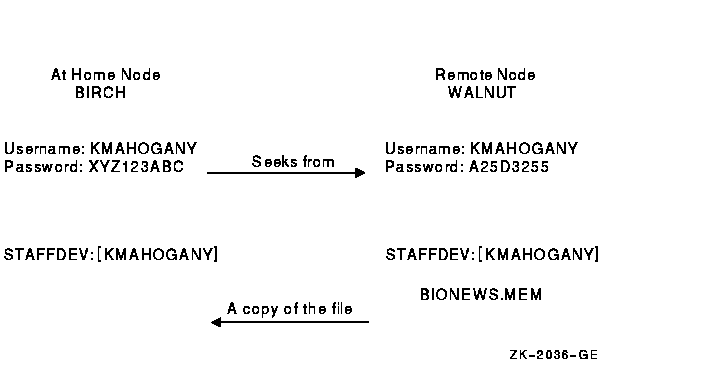

Network Logins

The system performs a network login when you initiate a network task on a remote node, such as displaying the contents of a directory or copying files stored in a directory on another node. Both your current system and the remote system must be nodes in the same network. In the file specification, you identify the target node and provide an access control string, which includes your user name and password for the remote node.

For example, a network login occurs when user GREG, who has an account on remote node PARIS, enters the following command:$ DIRECTORY PARIS"GREG 8G4FR93A"::WORK2:[PUBLIC]*.*;*

This command displays a listing of all the files in the public directory on disk WORK2. It also reveals the password 8G4FR93A. A more secure way to perform the same task would be to use a proxy account on node PARIS. For an example of a proxy login, see Section 10.5.3, ''Using Proxy Login Accounts to Protect Passwords''.

Batch Logins

The system performs a batch login when a batch job that you submitted runs. Authorization to build the job is determined at the time the job is submitted. When the system prepares to execute the job, the job controller creates a noninteractive process that logs in to your account. No password is required when the job logs in.

1.6. Login Failures

|

Failure Indicator |

Reason |

|---|---|

|

No response from the terminal |

A defective terminal, a terminal that requires a system password, or a terminal that is not powered on. |

|

No response from any terminal |

The system is down. |

|

No response from the terminal when you enter the system password |

The system password changed. |

|

System messages: | |

|

"User authorization failure" |

A typing error in your user name or password. The account or password expired. |

|

"Not authorized to log in from this source" |

Your particular class of login (local, dialup, remote, interactive, batch, or network) is prohibited. |

|

"Not authorized to log in at this time" |

You do not have access to log in during this hour or this day of the week. |

|

"User authorization failure" (and no known user failure occurred) |

An apparent break-in has been attempted at the terminal using your user name, and the system has temporarily disabled all logins at that terminal by your user name. |

The following sections describe the reasons for login failure in more detail.

1.6.1. Terminals That Require System Passwords

You cannot log in if the terminal you attempt to use requires a system password and you are unaware of the requirement. All attempts at logging in fail until you enter the system password.

If you know the system password, perform the steps described in Section 1.3.5, ''Entering a System Password''. If your attempts fail, it is possible that the system password has been changed. If you do not know the system password and you suspect that this is the problem, try to log in at another terminal or request the new system password.

1.6.2. Login Class Restrictions

If you attempt a class of login that is prohibited in your UAF record, your login will fail. For example, your security administrator can restrict you from logging in over the network. If you attempt a network login, you receive a message telling you that you are not authorized to log in from this source.

Your security administrator can restrict your logins to include or exclude any of the following classes: local, remote, dialup, batch, or network.

1.6.3. Shift Restrictions

Another cause of login difficulty is failure to observe your shift restrictions. A system manager or security administrator can control access to the system based on the time of day or the day of the week. These restrictions are imposed on classes of logins. The security administrator can apply the same work-time restrictions to all classes of logins or choose to place different restrictions on different login classes.

If you attempt a login during a time prohibited for that login class, your login fails. The system notifies you that you are not authorized to log in at this time.

1.6.4. Batch Jobs During Shift Restrictions

When shift restrictions apply to batch jobs, jobs you submit that are scheduled to run outside your permitted work times are not run. The system does not automatically resubmit such jobs during your next available permitted work time. Similarly, if you have initiated any kind of job and attempt to run it beyond your permitted time periods, the job controller aborts the uncompleted job when the end of your allocated work shift is reached. This job termination behavior applies to all jobs.

1.6.5. Failures During Dialup Logins

Your security administrator can control the number of opportunities you are given to enter a correct password during a dialup login before the connection is automatically broken.

If your login fails and you have attempts remaining, press the Enter key and try again. You can do this until you succeed or reach the limit. If the connection is lost, you can redial the access line and start again.

The typical reason for limiting the number of dialup login failures is to discourage unauthorized users attempting to learn passwords by trial and error. They already have the advantage of anonymity because of the dialup line. Of course, limiting the number of tries for each dialup does not necessarily stop this kind of break-in attempt. It only requires the perpetrator to redial and start another login.

1.6.6. Break-In Evasion Procedures

If anyone has made a number of failed attempts to log in at the same terminal with your user name, the system can respond as though a break-in attempt is in progress. That is, the system concludes that someone is attempting to gain illegal access to the system by using your user name.

At the discretion of your security administrator, break-in evasion measures can be in effect for all users of the system. The security administrator controls how many password attempts are allowed over what period of time. Once break-in evasion tactics are triggered, you cannot log in to the terminal—even with your correct password—during a defined interval. Your security administrator can tell you how long you must wait before reattempting the login, or you can move to another terminal to attempt a login.

If you suspect that break-in evasion is preventing your login and you have not personally experienced any login failures, contact your security administrator immediately. Together, you should attempt another login and check the message that reveals the number of login failures since the last login to confirm or deny your suspicion of break-in attempts. If your system does not normally display the login message, your security administrator can use the Authorize utility (AUTHORIZE) to examine the data in your UAF record. With prompt action, your security administrator can locate someone attempting logins at another terminal.

1.7. Changing Passwords

Changing passwords on a regular basis promotes system security. To change your password, enter the DCL command SET PASSWORD.

The system manager can allow you to select a password on your own or can require that you use the automatic password generator when you change your password. If you select your own password, note that the password must follow system restrictions on length and acceptability (see Section 1.3.3, ''Restrictions on Passwords'').

There is no restriction on how many times you can change your password in a given period of time.

$ SET PASSWORD Old password: New password: %SET-F-INVPWDLEN, password length must be between 12 and 32 characters; password not changed

1.7.1. Selecting Your Own Password

$ SET PASSWORD New password: Verification:

If you fail to enter the same new password twice, the password is not changed. If you succeed in these two steps, there is no notification. The command changes your password and Enters you to the DCL prompt.

Even though your security administrator might not require the password generator, you are strongly encouraged to use it to promote the security of your system.

1.7.2. Using Generated Passwords

Note

The password generator uses basic syllabic rules to generate words but has no real knowledge of any language. As a result, it can unintentionally produce words that are offensive.

$ SET PASSWORD Old password:reankuna rean-ku-na

cigtawdpau cig-tawd-pau adehecun a-de-he-cun ceebatorai cee-ba-to-rai arhoajabad ar-hoa-ja-bad Choose a password from this list, or press Enter to get a new list

New password:

Verification:

$

The user correctly specifies the old password and presses the Enter key. | |

The system responds with a list of five password choices ranging in length from 8 to 10 characters. Usually, the password that is easiest to pronounce is easiest to remember; therefore, it is the best choice. On OpenVMS VAX systems, representations of the same word divided into syllables are displayed to the right of each password choice (as shown here). | |

The system informs the user that it is possible to request a new list by pressing the Enter key in response to the prompt for a new password. | |

The user enters one of the first five possible passwords and presses the Enter key. | |

The system recognizes that this password is one provided by the automatic password generator and responds with the verification prompt. The user enters the new password again and presses Enter. | |

The system changes the password and responds with the DCL prompt. |

1.7.3. Generated Passwords: Disadvantages

There is a possibility that you might not remember your password choice. However, if you dislike all the password choices in your list or think none are easy to remember, you can always request another list.

There is a potential for disclosure of password choices from the display that the command produces. To protect your account, change your password in private. If you perform the change on a video terminal, clear the display of password choices from the screen after the command finishes. If you use a printing terminal, properly dispose of all hardcopy output.

If you later realize that you failed to protect your password in these ways, change your password immediately. Depending on site policy or your own judgment concerning the length of time your account was exposed, you should notify your security administrator that a security breach could have occurred through your account.

1.7.4. Changing a Secondary Password

To change a secondary password, use the DCL command SET PASSWORD/SECONDARY. You are prompted to specify the old secondary password and the new secondary password, just as in the procedure for changing the primary password. To remove a secondary password, press the Enter key when you are prompted for a new password and verification.

You can change primary and secondary passwords independently, but both are subject to the same change frequency because they share the same password lifetime.

1.7.5. Changing Passwords at Login

Even if your current password has not yet expired, you can change your password when you log in to the system by including the /NEW_PASSWORD qualifier with your user name. When you enter the /NEW_PASSWORD qualifier after your user name, the system prompts you to set a new password immediately after login.

WILLOW - A member of the Forest Cluster

Username: RWOODS/NEW_PASSWORD

Password:

Welcome to OpenVMS on node WILLOW

Last interactive login on Tuesday, 7-NOV-2002 10:20

Last non-interactive login on Monday, 6-NOV-2002 14:20

Your password has expired; you must set a new password to log in

New password:

Verification:1.8. Password and Account Expiration Times

Your system manager can set up your account so that your password, or the account itself, expires automatically on a particular date and time. Password expiration times promote system security by forcing you to change your password on a regular basis. Account expiration times help to ensure that accounts are available only for as long as they are needed.

1.8.1. Expired Passwords

WARNING – Your password expires on Thursday 11-DEC-2002 15:00

Your password has expired; you must set a new password to log in New password:

The system prompts you for a new password or, if automatic password generation is enabled, asks you to select a new password from those listed. You can abort the login by pressing Ctrl/Y. At your next login attempt, the system again prompts you to change your password.

1.8.2. Using Secondary Passwords

If secondary passwords are in effect for your account (see Section 1.3.4, ''Types of Passwords''), the secondary password expires at the same time as the primary one. You are prompted to change both passwords. If you change the primary password and press Ctrl/Y before changing the secondary password, the login fails. The system does not record a password change.

1.8.3. Failure to Change Passwords

WARNING -- Your password has expired; update immediately with SET PASSWORD!

At this point, if you do not change the password or if the system fails before you have the opportunity to do so, you will be unable to log in again. To regain access, see your system manager.

1.8.4. Expired Accounts

If you need your account for a specific purpose for a limited time only, the person who creates your account may specify a period of time after which the account lapses. For example, student accounts at universities are typically authorized for a single semester at a time.

Expired accounts deny logins automatically. You receive no advance warning message before the account expiration date, so it is important to know in advance your account duration. The account expiration resides in the UAF record, which can be accessed and displayed only through the use of the OpenVMS Authorize utility (AUTHORIZE) by users with the SYSPRV privilege or equivalent—normally, your system manager or security administrator.

When your account expires, you receive an authorization failure message at your next attempted login. If you need an extension, follow the procedures defined at your site.

1.9. Guidelines for Protecting Your Password

Illegal system accesses involving the use of a correct password are more often traced to disclosure of the password by its owner than to surreptitious discovery. It is vital that you do not reveal your password to anyone.

Select reasonably long passwords that cannot be guessed easily. Avoid using words in your native language that appear in a dictionary. Consider including digits in your password. Alternatively, let the system generate passwords for you automatically.

Never write down your password.

Never give your password to another user. If another user obtains your password, change it immediately.

Do not include your password in any file, including the body of an electronic mail message. If anyone else reveals a password to you, delete the information promptly.

The character strings that appear in conjunction with your actual password can make it easy for someone to find your password in a file. For example, a quotation mark followed by two colons ("::) always comes after a user name and password in an access control string. Someone attempting to break into the system could obtain your password by searching inadequately protected files for this string. Another way in which you might reveal your password is by using the word "password" in a text file, for example:My password is GOBBLEDYGOOK.

Do not use the same password for accounts on different systems.

An unauthorized user can try one password on every system where you have an account. The account that first reveals the password might hold little information of interest, but another account might yield more information or more privileges, ultimately leading to a far greater security breach.

Before you log in to a terminal that is already on, invoke the secure terminal server feature (if enabled) by pressing the Break key. This is particularly relevant when you are working in a public terminal room.

Change your password every 3 to 6 months. VSI warns against sharing passwords. If you do share your password, change it every month.

Change your password immediately if you have any reason to suspect it might have been discovered. Report such incidents to your security administrator.

Log off a terminal you expect to leave unattended.

Unauthorized users could use the terminal for malicious purposes, such as loading a password-stealing program.

Check your last login messages routinely. Be alert for login failure counts seem unusual. If you observe any unusual failure during a login, change your password immediately and notify your security administrator.

1.10. Recognizing System Responses

By executing the command. Generally, you know your command has executed successfully when the system prompt Enters (by default, the dollar sign).

By executing the command and informing you in a message what it has done.

By informing you of errors, if execution of a command is unsuccessful.

By supplying values (defaults) you have not supplied.

1.10.1. Default Actions

A default is the value supplied by the operating system when you do not specify one yourself. For example, if you do not specify the number of copies as a qualifier for the PRINT command, the system uses the default value 1. The operating system supplies default values in several areas, including command qualifiers and parameters. The defaults that the operating system uses with specific commands are described in each command's entry in the VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary.

1.10.2. Informational System Messages

$ PRINT MYFILE.LIS

Job MYFILE (queue SCALE_PRINT, entry 210) started on SYS$PRINTNot all commands display informational messages. Successful completion of a command is usually indicated when the DCL prompt Enters. Unsuccessful completion is always indicated by one or more error messages.

1.10.3. System Error Messages

$ CAPY ) %DCL-W-IVVERB, unrecognized command verb - check validity and spelling \CAPY\ $

DCL-W-IVVERB

|

DCL |

The OpenVMS facility or component name that Entered the error. In this example, the message is from DCL, the default command interpreter. |

|

W |

A severity level that indicates a warning. Other severity levels include S (success), I (information), E (error), and F (fatal or severe error). |

|

IVVERB |

The type of message. The message can be identified by the mnemonic IVVERB in the OpenVMS system messages documentation or by using the Help Message utility (MSGHLP) described in Section 1.11.3, ''Getting Help on System Messages''. |

$ PRINT NOFILE.DAT %PRINT-E-OPENIN, error opening CLASS1:[MAYMON]NOFILE.DAT; as input -RMS-E-FNF, file not found $

The first message is from the PRINT command. It tells you it cannot open the specified file. The second message indicates the reason for the first; that is, the file cannot be found. RMS refers to the OpenVMS file-handling software, Record Management Services; error messages related to file handling are generally OpenVMS RMS messages.

1.10.4. Checking Your Current Process

If you suspect that your process is not doing what you think it should be doing, press Ctrl/T. Ctrl/T displays a single line of statistical information about the current process. The statistical information includes node and user name, current time, current process, central processing unit (CPU) usage, number of page faults, level of I/O activity, and memory usage, which is listed in number of CPU-specific pages.

GREEN::MCCARTHY 13:45:02 EVE CPU=00:00:03.33 PF=778 IO=295 MEM=315

To refresh the screen, press Ctrl/W.

Ctrl/T is disabled by default. If you know your system is running and Ctrl/T does not display statistical information, you can enable Ctrl/T with the DCL command SET CONTROL=T. Enter the command at DCL level (at the dollar sign ($) prompt), then press Ctrl/T again. Ctrl/T will remain in effect for the duration of your process, unless it is disabled from a program or command such as SET NOCONTROL=T. Note that your terminal must be set to BROADCAST mode for Ctrl/T to display on your screen. BROADCAST mode controls whether reception of broadcast messages (such as those issued by MAIL and REPLY) is enabled. To set your terminal to BROADCAST mode, enter the DCL command SET TERMINAL/BROADCAST at the DCL prompt.

1.11. Getting Help About the System

When you are logged in to the operating system, you can obtain information about using the system and available commands by using the HELP command. You can also get help on system messages by entering the HELP/MESSAGE command as shown in Section 1.11.3, ''Getting Help on System Messages''.

1.11.1. Using Online Help

| Step |

Task |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Enter HELP at the DCL prompt and press Enter. HELP displays a list of topics and the Topic? prompt. |

| 2 |

To see information about one of the topics, type the topic name after the prompt and press Enter. |

| 3 |

If you want information on one of the subtopics, type the name after the prompt and press Enter. HELP displays information about that subtopic. |

| 4 |

To redisplay the SHOW USERS topic and the list of subtopics, enter a question mark (?) at the Subtopic? prompt. If you want to read all of the listed subtopics, enter an asterisk (*). |

| 5 |

If you want information on another topic, press Enter. Help displays the Topic? prompt. |

| 6 |

To exit Help, press Enter until you Enter to the DCL prompt. |

$ HELP

HELP

.

. (HELP message text and subtopics)

.

Topic? SHOW USERS

SHOW

USERS

Displays the user name and node name (in a VAXcluster environment)

of interactive, subprocess, and batch users on the system.

Format

SHOW USERS [username]

Additional information available:

PARAMETER QUALIFIER

/BATCH /CLUSTER /FULL /INTERACTIVE /NETWORK /NODE

/OUTPUT /SUBPROCESS

Examples

SHOW USERS Subtopic? EXAMPLES

SHOW

USERS

Examples

.

. (SHOW USERS Examples message text and subtopics, if any)

.

SHOW USERS Subtopic?

SHOW Subtopic?

Topic?

$1.11.2. Getting Help on Specific Commands

$ HELP SHOW USERS

If you need help but do not know what command or system topic to specify, enter the command HELP with the word HINTS as a parameter. Each task name listed in the HINTS text is associated with a list of related command names and system information topics.

The VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary contains more information about the HELP command.

1.11.3. Getting Help on System Messages

$ HELP/MESSAGE

$ HELP/MESSAGE BADACP

$ HELP/MESSAGE/STATUS=%X00038090

$ SHOW SYMBOL $STATUS $STATUS == "%X00038090"

The Help Message utility allows you to update the messages database with your own messages or to add comments to existing message descriptions. You can also extract a subset of messages from the messages database to create and print your own customized messages documentation. For details on how to use the Help Message utility, see OpenVMS System Messages: Companion Guide for Help Message Users.

1.12. Logging Out of the System

When you finish using the system, always log out. This prevents unauthorized users from accessing your account and the system. It is also a wise use of system resources; the resources you no longer need are available for other users.

$ LOGOUT

$ LOGOUT HARRIS logged out at 11-DEC-2002 12:42:48.12

You can log out of the system only when you are at the DCL prompt ($). You cannot enter the LOGOUT command while you are compiling or executing a program, using a text editor (such as EDT or EVE), or running a utility (such as Mail). First you must exit the program, editor, or utility. When the system displays the DCL prompt, you can log out.

1.12.1. Obtaining Accounting Information

$ LOGOUT/FULL

SIMPSON logged out at 11-DEC-2002 12:42:48.12 Accounting information: Buffered I/O count: 8005 Peak working set size: 212 Direct I/O count: 504 Peak virtual size: 770 Page faults: 1476 Mounted volumes: 0 Charged CPU time:0 00:00:50.01 Elapsed time:0 02:27:43.06

1.12.2. Ending a Remote Session

Use the remote system's logout procedure (for example, on an OpenVMS system, use the LOGOUT command).

Press Ctrl/Y twice to obtain the host system's prompt, which asks whether you want to abort the remote session. Answer YES (Y) if you want to abort the remote session. This method works regardless of the type of system running on the remote node.

When you end a remote session, the system displays the message "%REM-S-END, control Entered to node NODENAME::" and Enters you to the process on the system from which you made the remote node connection.

1.12.3. Lost Network Connections

If a TCP/IP network connection to a remote system is lost, TCP/IP uses the best-effort delivery protocol, which is a characteristic of network technologies that attempts to deliver data but does not try to recover if there is an error such as a line failure.

If a DECnet network connection to a remote system is lost, DECnet will retransmit your data in an attempt to reestablish communications. If DECnet is unable to reestablish communications within a predetermined timeout period, your connection to the remote system is terminated, and the system displays the message "Path lost to partner."

1.13. Logging Out Without Compromising System Security

Logging out of a session conserves system resources and protects your files. Leaving a terminal on line represents one of the greatest sources of inside break-ins. When you leave your terminal on line and your office open, you have effectively given away your password and your privileges and have left your files and those of the other members of your group unprotected. Any user can easily and quickly transfer all files accessible through your account. A malicious insider could rename and delete your files and any other files to which you have write access. If you have special privileges, especially privileges in the Files or All category, a malicious user can do major damage.

If you are working on a system that does not automatically lock after a determined time of inactivity, you should log out when you leave your office even for a brief period of time. If you have performed remote logins, you must log out of each node.

Prevents others from taking advantage of an open access line. To access the line, someone must know the access number and must personally redial.

Is especially important if the dialup line you use is in a public area or where someone might use the terminal after you.

Saves resources by reducing the required number of dialup lines.

1.14. Networks

When computer systems are linked together, they form a network. Operating systems in an OpenVMS network are able to communicate with each other and share information and resources. Each system in a network is called a network node or host and is identified by a unique name or address. Host and node are used interchangeably, and mean a system connected to a network.

With OpenVMS, you have a choice of networking protocols. You can use the VSI TCP/IP Services for OpenVMS product or VSI's DECnet products within a single network, or you can have an environment where both products exist. VSI's primary network strategy for OpenVMS is TCP/IP, the industry-standard network protocol suite.

1.14.1. Network Nodes

When you are logged in to a network node, you can communicate with other nodes in the network. The node at which you are logged in is called the local node; other nodes on the network are called remote nodes. If you have access to an account on a remote node, you can log in to that account from your local node and perform tasks on that node while remaining connected to your local node.

Section 1.5.2, ''Noninteractive Logins'' describes how to log in to a remote node. Additional tasks you can perform on remote nodes are described in the appropriate chapters of this manual.

1.14.2. Executing Programs over Networks

Because of support provided by TCP/IP and DECnet software, programs can execute across the network as if they were executing locally. Because the network software is integrated within the operating system, it is easy to write programs that access remote files. To access a remote file in an application program, you need only include the name of the remote node and any required access control information in the file specification.

Note

In the examples of remote operations in this manual, proxy accounts enable users to perform operations on remote systems. Proxy accounts are one way users can access remote systems. For additional ways to access remote systems, see the VSI OpenVMS System Manager's Manual.

Chapter 2. Using DCL to Interact with the System

Get information about the system

Work with files

Work with disks, magnetic tapes, and other devices

Modify your work environment

Develop and execute programs

Provide security and ensure that resources are used efficiently

|

Command |

Task |

|---|---|

|

COPY |

Makes a copy of a specified file |

|

COPY/FTP |

Transfers files between hosts over a TCP/IP network |

|

CREATE |

Creates files or directories |

|

DELETE |

Erases a specified file and removes it from a directory |

|

DIRECTORY |

Displays the contents of a directory (list of files) |

|

EDIT |

Invokes the EVE text editor, allowing for viewing or modifying the contents of a text file |

|

LOGOUT |

Ends your terminal session |

|

|

Sends a specified file to a printer for printing |

|

RENAME |

Changes the name or the location of a specified file |

|

SET |

Controls how you see the system on the screen |

|

SHOW |

Displays the status of the system |

|

TYPE |

Displays the contents of a specified file on the screen |

Entering DCL commands

The DCL command line

Rules for entering DCL commands

Entering parameters

Entering qualifiers

Entering dates and times as values

Recalling commands

Editing the DCL command line

Defining terminal keys

Key sequences

Differences in Your Local Environment

Use a different command language interpreter

Change the default action of some standard DCL commands

Disable some DCL commands

Alter some system defaults, such as the DCL prompt

Configure an environment with extended file specifications

For additional information on the commands, qualifiers, and parameters discussed in this chapter, refer to the VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary and online help.

2.1. Entering Commands

To enter a DCL command, type the command at the DCL prompt ($) and press Enter. DCL is not usually case sensitive; you can enter commands in either uppercase or lowercase letters.?

$ SHOW TIME

11-DEC-2002 15:41:43 $

2.1.1. Usage Modes

Interactive

In interactive mode, you enter commands from your terminal. One command has to finish executing before you can enter another.

Batch

In batch mode, the system creates another process to execute commands on your behalf. A batch job is a command procedure or program that is submitted to the operating system for execution as a separate user process. After you submit the command procedure for batch execution, you can continue to use your terminal interactively.

Batch jobs and network processes use DCL in batch mode. See Chapter 16, "Understanding Processes and Batch Jobs" for more information about processes.

2.1.2. Types of DCL Commands

Built-in commands

These commands are built into the DCL interpreter and are executed internally.

Commands that invoke programs

DCL calls another program to execute the command rather than executing it internally. The program invoked to execute a command is referred to as a command image. This command image can be either an interactive program, a utility (such as Mail), or a noninteractive program (such as COPY).

Foreign commands

A symbol that executes an image is referred to as a foreign command. A foreign command executes an image whose name is not recognized by the command interpreter as a DCL command. Refer to Chapter 12, "Defining Symbols, Commands, and Expressions" for complete information on symbols.

2.2. The DCL Command Line

DCL, like any language, has its own vocabulary and usage rules. DCL is made up of words (vocabulary) and word order (syntax or format). The following sections describe these two elements and explain how to construct a valid DCL command.

$ PRINT/COPIES = 5 GROCERY.LIS Enter

DCL prompt The dollar sign ($) is the default DCL prompt. When you work interactively with DCL, DCL displays the prompt when it is ready to accept a command. | |

DCL command A DCL command specifies the name of the command. The command can be a built-in command, a command that invokes a program, or a foreign command. In this example, the DCL command is PRINT. | |

Qualifier A qualifier modifies the action taken by the command. Some qualifiers modify the entire command, while others can modify specific command parameters. Some qualifiers can accept values. Qualifiers are always preceded by a slash (/). In this example, the qualifier is /COPIES. | |

Value A value modifies a qualifier and is often preceded by an equal sign (=). A value can be a file specification, a character string, a number, or a DCL keyword. A keyword is a word reserved for use in certain specified formats. In this example, the value is 5 (for 5 copies). | |

Parameter A parameter specifies what the command acts upon. You must position parameters in a specified order within the command. Examples of parameter values include file specifications, queue names, and logical names. | |

Enter key The Enter key ends the DCL command line and signals to the system that the command is ready for processing. |

Labels

Labels identify lines in command procedures. Use labels only within command procedures, which are described in Chapter 13, "Introduction to Command Procedures" and Chapter 14, "Advanced Programming with DCL".

Keywords

Keywords are words that are defined for use in certain specified formats. You must use keywords exactly as listed in the description of the particular DCL command you want to specify. For example, system, owner, group, and world are DCL keywords for the /PROTECTION qualifier of the SET SECURITY command. A DCL keyword can also have a value assigned to, or associated with, it.

Wildcard characters

Wildcard characters are the asterisk (*), percent sign (%), ellipsis (...), and hyphen (-).

The asterisk (*) is a multi-character wildcard and the percent sign (%) is a single-character wildcard. These wildcard characters can be used within or in place of a file name, file type, or a directory name. The asterisk can also be used in place of the file version number. The ellipsis (...) can be used in the directory name to represent all subdirectories of the current or listed directory. The hyphen (-) can be used in the directory name to represent the level above the current directory.

For information about using wildcard characters with files and directories, see Section 3.2, ''Using Wildcards with File Names'', Section 4.5, ''Using Wildcards to Search the Directory Structure'', and VSI OpenVMS Guide to Extended File Specifications.

2.2.1. Syntax

Just as a spoken language depends on the order of words to create meaning, DCL requires that you put the correct elements of the command line in a specific word order or format.

command/qualifier=value=keyword

command parameter/qualifier

When you enter a DCL command, some parameters are required; they must be entered on the command line. If you do not enter them, the system prompts you to supply the missing information. A line beginning with an underscore (_) means that the system is waiting for your response.

When you are prompted for an optional parameter, press Enter to omit it. At any prompt, after you enter the required parameter, you can enter one or more of the remaining parameters and any additional qualifiers.

Note that you must enclose in quotation marks ("") any parameter containing a slash (/) or at sign (@).

$ TYPE _File: WATER.TXT

2.2.2. Canceling Commands

If you press Ctrl/Z after a command prompt, DCL ignores the command and redisplays the DCL prompt.

2.2.3. Using Defaults

Some items, called defaults, need not be specified on the command line. When DCL performs an operation by default, it assigns a command certain values or performs certain functions associated with that command even though you may not have explicitly specified those values or functions when you entered the command. In general, the values and functions are those considered typical or expected by users.

DCL supplies default values in several areas, including command parameters and qualifiers. For parameter defaults, see the sections in this manual that describe the specific DCL command. Qualifier defaults are described in Section 2.5, ''Entering Qualifiers''.

$ PRINT/COPIES=4 MYFILE.TXT

2.2.4. Entering Multiple Line Commands

|

Step |

Task |

|---|---|

|

1 |

End the command line with a hyphen (-) and press Enter. The system displays an underscore (_) followed by the DCL prompt ($). |

|

2 |

Enter the rest of the command line after this prompt. A line beginning with an underscore means that the system is waiting for your response. |

You must include the appropriate spaces between command names, parameters, and so on.

Pressing Enter after the hyphen does not add a space.

There is no restriction to the number of continued lines you can use to enter a command, as long as you do not exceed the 1024-character limit.

You can also enter a long command line without specifying a hyphen; the system automatically wraps text to the next line. However, separating portions of the command lines with hyphens makes the command line easier to read.

$ COPY/LOG FORMAT.TXT,FIGURE.TXT,ARTWORK.TXT - _$ SAVE.TXT

Pipelining (a sequence of commands)

Input/output redirection

Multiple and conditional command execution

Background processing

For more detailed information, see Section 14.20, ''Using the PIPE Command'' and the description of the PIPE command in the VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary: N–Z.

2.3. Rules for Entering DCL Commands

Use any combination of uppercase and lowercase letters. The DCL interpreter translates lowercase letters to uppercase. Uppercase and lowercase characters in parameter and qualifier values are equivalent unless enclosed in quotation marks (" ").

Separate the command name from the first parameter with at least one blank space or a tab.

Separate each additional parameter from the previous parameter or qualifier with at least one blank space or a tab.

Begin each qualifier with a slash (/). The slash serves as a separator and need not be preceded by blank spaces or tabs.

If a parameter or qualifier value includes a blank space or a tab, enclose the parameter or qualifier value in quotation marks.

You cannot specify null characters (<NUL>) on a DCL command line, even if you enclose the null character in quotation marks.

Include no more than 127 elements (parameters, qualifiers, and qualifier values) in each command line.

Each element in a command must not exceed 255 characters. The entire command must not exceed 1024 characters after all symbols and lexical functions are converted to their values.

You can abbreviate a command as long as the abbreviated name remains unique among the defined commands on a system. DCL looks only at the first four characters for uniqueness.

The following commands are equal:$ PRIN/COPI=2 FORMAL_ART.TXT $ PRINT/COPIES=2 FORMAL_ART.TXT

For greater clarity and to ensure that your command procedures are upwardly compatible, do not abbreviate commands in command procedures. See Chapter 13, "Introduction to Command Procedures" and Chapter 14, "Advanced Programming with DCL" for more information about using commands in command procedures.

2.4. Entering Parameters

File specifications are the most common type of parameter. DCL commands can accept input file specifications (files that are acted upon by a command) and output file specifications (files that are created by a command).

- Square brackets ([]) in command descriptions indicate optional items. For example, you do not have to enter a file specification in the following command:

DIRECTORY [file-spec]

- In a command description, anything not enclosed in square brackets is required. For example, you must enter a device name in the following command:

SHOW PRINTER device-name

In general, precede an output file parameter with an input file parameter.

A parameter can be one item or a series of items. If you enter a series of items, separate the items with commas (,) or plus signs (+). Any number of spaces or tab characters can precede or follow a comma or a plus sign. Note that some commands regard the plus sign as a concatenator, not as a separator.

Examples

$ COPY LISTS.TXT FORMAT.TXT

DELETE file-spec[,...]

$ COPY PLUTO.TXT,SATURN.TXT,EARTH.TXT PLANETS.TXT

2.5. Entering Qualifiers

Command

Positional

Parameter

You can abbreviate any qualifier name as long as the abbreviated name remains unique among all qualifier names for the same command. However, to ensure that your command procedures are upwardly compatible, do not abbreviate commands and qualifiers in command procedures.

Commands have default qualifiers; you do not have to specify a qualifier unless it is different from the command default. The following sections describe types of qualifiers and qualifier defaults. The VSI OpenVMS DCL Dictionary contains default information for specific commands.

2.5.1. Command Qualifiers

A command qualifier modifies a command and can appear anywhere in the command line. However, it is a good practice to place the qualifier after the command name. If you are specifying multiple qualifiers, you should place a command qualifier with other command qualifiers that follow the command name.

$ PRINT/QUEUE=LN03_PRINT SATURN.TXT,EARTH.TXT

2.5.2. Positional Qualifiers

A positional qualifier can modify commands or parameters and has different meanings depending on where you place it in the command string. If you place a positional qualifier after the command but before the first parameter, it affects the entire command string. If you place a positional qualifier after a parameter, it affects only that parameter.

$ PRINT/COPIES=2 SPRING.SUM,FALL.SUM $ PRINT SPRING.SUM/COPIES=2,FALL.SUM

2.5.3. Parameter Qualifiers

A parameter qualifier can be used only with certain types of parameters, such as input files and output files. For example, the BACKUP command accepts several parameter qualifiers that apply only to input and output file specifications.

$ BACKUP *.TXT/CREATED/BEFORE=11-DEC-2002 NEWFILE.TXT

2.5.4. Conflicting Qualifiers

If you use two or more contradictory qualifiers on a command line, the right-most qualifier overrides the others.

Some commands contain conflicting qualifiers that cannot be specified in the same command line. If you use incompatible qualifiers, the command interpreter displays an error message.

$ PRINT MYFILE/COPIES=3/BURST/COPIES=2/NOBURST EARTH.TXT

2.5.5. Values Accepted by Qualifiers

Qualifiers can accept keywords, file specifications, character strings, and numeric values. When you enter a value for a qualifier, separate the qualifier and the value with either an equal sign (=) or a colon (:).

Some qualifier keywords require additional information. In these cases, separate the keyword from its value with a colon or an equal sign.

To specify multiple keywords that require values, enclose the list in parentheses and separate the keyword and value with either an equal sign (=) or a colon (:).

Examples

$ PRINT/COPIES=3 MYFILE.DAT

$ PRINT/COPIES:3 MYFILE.DAT

$ SET SECURITY/PROTECTION:GROUP:RW MYFILE.DAT

$ SET SECURITY/PROTECTION=GROUP=RW MYFILE.DAT

$ SET SECURITY/PROTECTION=(OWNER=RWD,GROUP=RW) myfile.dat

$ SET SECURITY/PROTECTION=(OWNER:RWD,GROUP:RW) myfile.dat

2.6. Entering Dates and Times as Values

Absolute time

Delta time

Combination time (combines absolute and delta time formats)

2.6.1. Absolute Time Format

[dd-mmm-yyyy][:hh:mm:ss.cc]

|

dd |

Day of the month: an integer in the range 1 to 31 |

|

mmm |

Month: JAN, FEB, MAR, APR, MAY, JUN, JUL, AUG, SEP, OCT, NOV, or DEC |

|

yyyy |

Year: an integer |

|

hh |

Hour: an integer in the range 0 to 23 |

|

mm |

Minute: an integer in the range 0 to 59 |

|

ss |

Second: an integer in the range 0 to 59 |

|

cc |

Hundredths of a second: an integer in the range 0 to 99 |

You can truncate the date or the time on the right.

If you specify both a date and a time, include a colon between them.

The date must contain at least one hyphen.

You can omit any of the fields within the date and time as long as you include the punctuation marks that separate the fields.

A truncated or omitted date field defaults to the corresponding fields for the current date.

A truncated or omitted time field defaults to zero.

If you specify a past time in a command that expects the current or a future time, the current time is used.

|

TODAY |

The current day, month, and year at 00:00:00.0 o'clock |

|

TOMORROW |

00:00:00.00 o'clock tomorrow |

|

YESTERDAY |

00:00:00.00 o'clock yesterday |

|

Time Specification |

Result |

|---|---|

|

11-DEC-2002:13 |

1 p.m. on December 11, 2002 |

|

11-DEC |

Midnight at the beginning of December 11 this year |

|

15:30 |

3:30 p.m. today |

|

19– |

Midnight on the 19th day of the current year and month |

|

19–:30 |

12:30 a.m. on the 19th of this month |

2.6.2. Delta Time Format

"+[dddd-][hh:mm:ss.cc]"

|

dddd |

Number of days; an integer in the range 0 to 9999 |

|

hh |

Number of hours; an integer in the range 0 to 23 |

|

mm |

Number of minutes; an integer in the range 0 to 59 |

|

ss |

Number of seconds; an integer in the range 0 to 59 |

|

cc |

Number of hundredths of seconds; an integer in the range 0 to 99 |

If a qualifier is described as a value that can be expressed as an absolute time, a delta time, or a combination of the two, you must specify a delta time as if it were part of a combination time. For example, to specify a delta time value of five minutes from the current time, use "+:5" (not "0-0:5").

You can truncate a delta time on the right.

If you specify the number of days, include a hyphen.

You can omit fields within the time as long as you include the punctuation that separates the fields.

If you omit the time field, the default is zero.

|

Time Specification |

Result |

|---|---|

|

"+3-" |

3 days from now (72 hours) |

|

"+3" |

3 hours from now |

|

"+:30" |

30 minutes from now |

|

"+3-:30" |

3 days and 30 minutes from now |

|

"+15:30" |

15 hours and 30 minutes from now |

2.6.3. Combination Time Format

"[absolute time][+delta time]"

[absolute time][-delta time]The variable fields and default fields for absolute and delta time values are the same as those described in the preceding sections.

Precede the delta time value by a plus or minus sign. Note that the minus sign is the same keyboard key as the hyphen.

Enclose the entire time specification in quotation marks if a plus or minus sign precedes the delta time value.

Omit the absolute time value if you want to offset the delta time from the current date and time.

Specify date and time information as completely as possible.

|

Time Specification |

Result |

|---|---|

|

"+5" |

5 hours from now. |

|

"-1" |

Current time minus 1 hour. The minus sign (-) indicates a negative offset. The 1 is interpreted as an hour, not a day, because it is not followed by a hyphen. |

|

"+:5" |

5 minutes from now. |

|

"-:5" |

Current time minus 5 minutes. |

|

"-1-00" |

Current time minus 1 day. The minus sign (-) indicates a negative offset. The hyphen (-) separates the day from the time field. |

|

"31-DEC:+:5" |

12:05 a.m. on December 31 of the current year. The absolute time specification (before the colon) defaults to midnight on December 31 of the current year. The plus sign (+) indicates a positive offset. |

|

31-DEC:-00:10 |

11:50 p.m. on December 30 of the current year. The absolute time specification (before the colon) defaults to midnight on December 31 of the current year. The minus sign (-) after DEC: indicates a negative offset. |

2.7. Recalling Commands

At the DCL prompt, you can recall previously typed command lines to avoid retyping long command lines. Once a command is displayed, you can reexecute or edit it.

On OpenVMS VAX systems, the recall buffer holds up to 20 previously entered commands.

On OpenVMS Alpha systems, the recall buffer holds up to 254 previously entered commands.

Pressing Ctrl/B

Using up arrow and down arrow keys

Using the RECALL command

2.7.1. Pressing Ctrl/B

Pressing Ctrl/B once recalls the previous command line. Pressing Ctrl/B again recalls the line before the previous line and so on to the last saved command line.

2.7.2. Using Arrow Keys

Using the up arrow and down arrow keys recalls the previous and successive command, respectively. Press the arrow keys repeatedly to move through the commands.

2.7.3. Using the RECALL Command

To examine previously typed command lines, type RECALL/ALL. After reviewing the available commands, you can recall a particular command line by typing RECALL and the number of the desired command.

You can also follow RECALL with the first characters of the command line you want to display. RECALL scans the previous command lines (beginning with the most recent one) and Enters the first command line that begins with the characters you typed.

Examples

$ RECALL/ALL

1 SET DEFAULT DISK2:[MARSHALL] 2 EDIT ACCOUNTS.COM 3 PURGE ACCOUNTS.COM 4 DIRECTORY/FULL ACCOUNTS.COM 5 COPY ACCOUNTS.COM [.ACCOUNTS]* 6 SET DEFAULT [.ACCOUNTS]

$ RECALL 4

After you press Enter, the system displays the fourth command in the list at the DCL prompt. The RECALL command itself is not placed in the buffer.

$ RECALL E

$ EDIT ACCOUNTS.COM

Note